Curious Questions: Who started the first charity shop?

Charity shops have become a staple of British high streets in the past decade, and more and more of us are doing our shopping there — particularly as times are tight. But what's the story behind them? Martin Fone unearths the history of the charity shop.

At some point 88% of us have bought something from a charity shop, according to the Charity Retail Association (CRA). In 2020 we spent £746 million in them, with the average spend per transaction reaching £6.53 in the summer of 2022. There are around 10,200, occupying 3.26% of the UK’s retail units, staffed by some 26,800 full time employees and over 186,000 volunteers. The high street in Frimley, where I live, has four of them, two, curiously, supporting the same institution.

Known as thrift shops in the States and oppies, short for opportunity shops, in Australia and New Zealand, charity shops seem to be more prevalent in Anglophone countries. Elsewhere, the sale of what the CRA call their ‘unique range of goods’ is transacted in the open, for example at the French brocante (flea market), vide-grenier (a car boot sale), or municipal braderie (a festival combining a flea market).

British charity shops have fought hard to dispel the image of being an ‘instructive inventory of the passé’, as Mary McCarthy described one in The Group (1954), a repository of outmoded trends and fashions infused with the faint aroma of mothballs. Nevertheless, over 90% of their turnover still comes from the sale of goods donated by well-wishers, who, if British Income Tax payers, can boost the retail value of their donations by a further 25% through the Government’s Gift Aid Scheme. Saving around 339,000 tonnes of textiles from disposal, they not only help a good cause but also make a small but valuable contribution to securing the planet’s future.

While shelves and racks still contain single-purpose kitchen appliances, clothing bought on a whim, and ornaments last seen on a grandparent’s dresser, a developing trend is to sell ‘bought-in goods’, discontinued lines from major retailers. All new and sold at discounted prices, in summer 2022 they made up around 7.3% of their total turnover.

Concerted efforts to ameliorate the conditions of the poor began in earnest in the 18th century. A ‘poor rate’ levied on parish householders, as well as establishing workhouses, helped those able to work but whose wages were too low to support their families by giving them ‘relief in aid of wages’ in the form of money, food, and clothing. Funds were also collected at balls, concerts, and charitable art exhibitions, wealthy philanthropists bequeathed substantial sums to charitable purposes, and single purpose charities such as The Foundling Hospital (1739) and the Marine Society (1756) were established to give unfortunate children a better start in life.

By the 19th century the charity bazaar or ‘fancy fair’ became a popular way to raise funds, receiving royal imprimatur in 1833 when Queen Adelaide, William IV’s wife, attended the ‘Grand Fancy Fair and Bazaar’ in London. Soon London was hosting more than a thousand charity functions a year and the idea spread throughout the country.

Bazaars were often grand affairs, offering entertainment in the form of puppet shows, fortune telling, plays and music, as well as selling a wide range of goods. They were often themed, with elaborate décor, actors dressed in costumes, and refreshments suitable for the occasion. Offering a rare opportunity for the sexes to mingle freely, patrons would dress in their Sunday best.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

They were not universally popular. Religious leaders criticised the materialism and false piety charity bazaars encouraged, while the Cornhill Magazine complained in 1861 that women manning the stalls used feminine ‘coaxing’ and ‘insinuating’ to persuade the public to part with their money.

Nevertheless, bazaars continued to be part of the social scene until the Second World War, although they were increasingly replaced by less elaborate ‘pop up’ charity fundraising events, such as jumble sales, and, later still, bring-and-buy sales. The first recorded jumble sale was held in Wollaston to raise funds for ‘church paraphernalia’, as the Northampton Mercury noted on January 5, 1889.

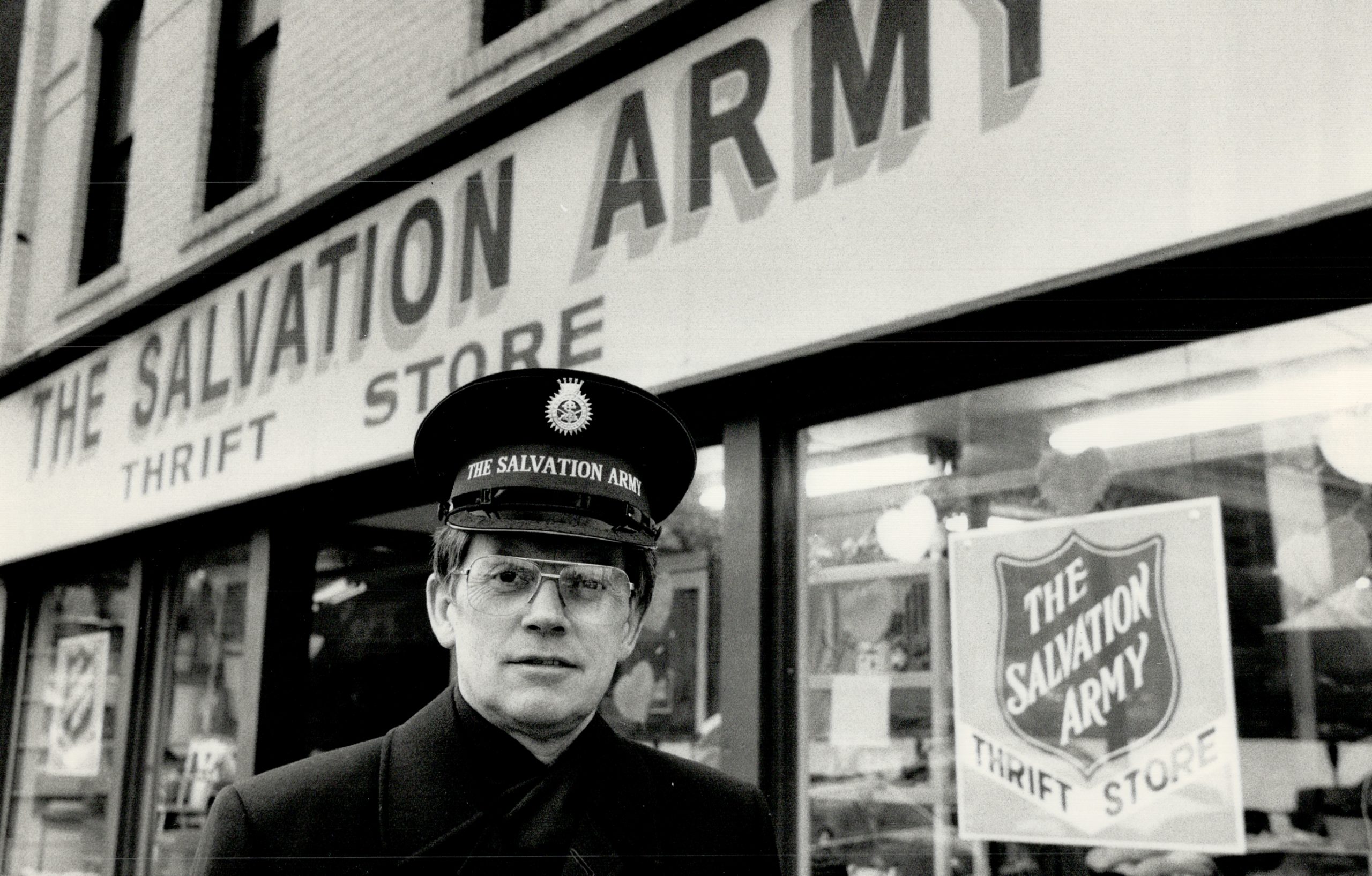

The earliest known fundraising shop was sited in Mayfair, selling flowers to support a mission in East London from 1870. The Salvation Army combined the two prevailing strands of charitable endeavour in the latter part of the 19th century, establishing ‘salvage stores’ to provide cheap second-hand clothing and furniture to the poor while giving Salvationists the opportunity for gainful employment by making and selling high-quality, branded goods, ranging from musical instruments to razor blades. The charity shop opened by the Wolverhampton Society for the Blind on Victoria Street in 1899 sold baskets, chair seating, and mats made by visually impaired men and women in their Alexandra Street workshop.

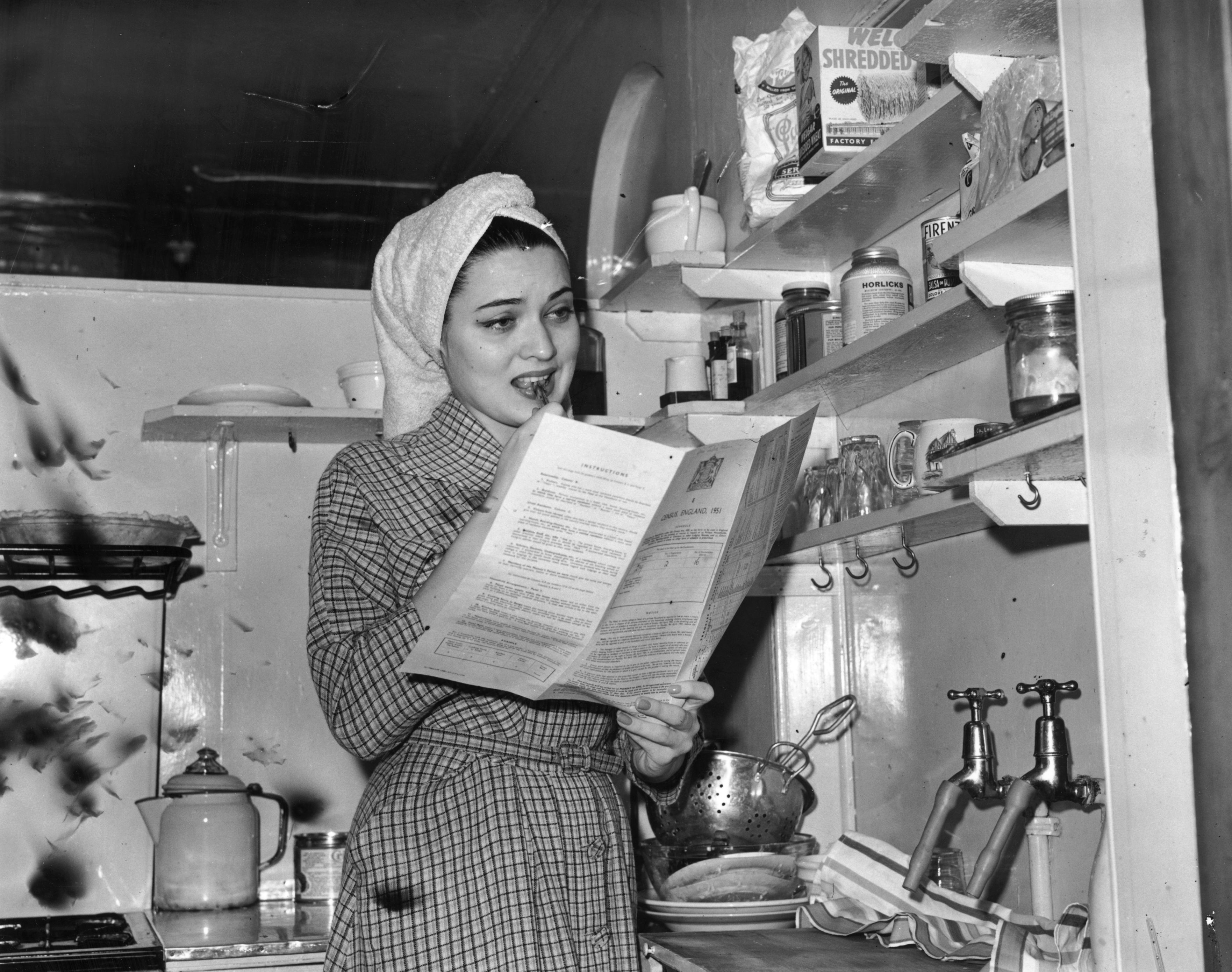

One of the very first charity shops as we know them now, the Edinburgh University Settlement’s ‘Everybody’s Thrift Shop’, opened in 1937 at 79a, Nicholson Street. Public reaction was astonishing, the Scotsman reporting on April 27th that people had queued for an hour before it opened its doors and police were present to ensure that the crowds did not overwhelm stallholders. Crystal, evening shawls, and furniture were among the goods on offer and one woman delightedly bought a handsome suit once worn, it was whispered, by a professor.

War spurred a boom in charity shops, the Red Cross opening their first on Old Bond Street in 1941, followed by over two hundred ‘permanent’ and around 150 ‘temporary’ gift shops. A condition of their licence from the Board of Trade was that purchase for re-sale was forbidden. The escalating humanitarian crisis in Nazi-occupied Greece led to the formation of the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief in 1943, which the following year organised it first ‘Greek Week’ campaign, soliciting donations from the public and raising £13,000 for the Greek Red Cross to assist the relief effort in Greece.

By 1947 as order was slowly restored to war-torn Europe, the committee, now referred to as Oxfam, converted its surplus stocks of clothing and other goods into cash by opening their first permanent shop in December 1947 on Broad Street in Oxford.

It was a model that proved successful and by the 1960s many charities had opened their own shops to raise funds mainly through the sale of second-hand clothing. They were beneficiaries of the rising standard of living coupled with the demise of the old ‘mend and make do’ attitude engendered by clothes’ rationing and the rise of throwaway consumerism. The public were now more willing to part with redundant clothing and make impulse purchases.

In the 1980s with supermarkets increasingly forcing specialist shops out of business, the Government gave charity shops significant incentives to take up redundant retail space, providing exemptions from Corporation Tax on profits, putting a zero VAT rating on donated goods sales and discounting property taxed by 80%. This led to them taking over more prime retail locations and spurred a discernible improvement in the way goods were presented and a rise in expertise and professionalism.

Although ideally placed to capitalise on 21st century concerns over sustainability and waste, they are not immune to modern pressures. That bellwether of real life, Mumsnet, reports the impact of rising prices in charity shops, an area of concern when consumers are increasingly buying out of necessity rather than on a whim.

The focus of their charitable endeavours might have changed over time, but charity shops are needed more than ever.

Curious questions: Who was the first person to receive the Victoria Cross?

Martin Fone retraces the history of the order and discovers the stories of its early recipients.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Should you bring a snowdrop into the house?

Martin Fone delves into Britain's collective passion for Galanthus and looks at the folklore that surrounds it.

Curious Question: When was the first census held?

As the UK prepares to compile this decade's census, Martin Fone retraces its history.

Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Curious Questions: Which came first — the plastic flower pot or the garden centre?

Martin Fone takes a look at the curiously intriguing tale of the evolution of nurseries in Britain.

Curious Question: Could the world’s smelliest fruit soon charge your phone?

Martin Fone dives into the world of pongy fruits and discovers why durian could be at the charging end of

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.