Curious Questions: Who invented the cardboard box?

Six months of online shopping have left Martin Fone buried in cardboard boxes — and that's put him in the mood to answer a curious question. Where do they all come from? And when did we start making them?

One of the fascinating features of the Covid-19 pandemic is how rapidly it has transformed our shopping habits. According to the Office for National Statistics the proportion of all retail sales made online in the UK in May 2020 was a record-breaking 33.4%. Although the percentage reduced to 31.8% in June, following the reopening of non-essential shops, it still represents a 50% increase from the February figure. We now are in danger of drowning in a sea of cardboard boxes.

Pre Covid-19, 80% of all products sold in the EU and the United States were packaged in cardboard and, here in Britain, we used 5 billion corrugated boxes a year, the equivalent of 83 per head. Whichever way you look at it, cardboard boxes are big business. Recycling some and stashing others away — in case they might come in handy one day — has become a routine occupation for most of us. Whose bright idea were cardboard boxes, anyway?

History is written by the winners, they say, and our version is very much Western-centric. When it comes to paper, and much else if the truth be told, the Chinese were streets (or should it be sheets?) ahead of us Occidentals, using a form of cardboard — made from sheets of treated mulberry bark — to wrap up and preserve foodstuffs as far back as the second century BC. In Europe, a stiffened form of paper, cardboard, was adopted less than five hundred years ago, and initially it was just used for printing or writing on.

The printing manual, Mechanick Exercises (1677), compiled by Theodore Low de Vinne and Joseph Mixon, contains the first Western reference to cardboard, noting that scabbards “mentioned in printers’ grammars from the last century were of cardboard or millboard”. In Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848), Helen makes a sketch of her beau on a piece of cardboard, complaining that ‘the pencil frequently leaves an impression upon cardboard that no amount of rubbing can efface’.

It was in the early 19th century, though, that people began to consider using cardboard for other purposes. A British industrialist, Sir Malcolm Thornhill is credited, in 1817, with making boxes out of cardboard. They were not padded or lined, just rudimentary cardboard boxes, rather like a breakfast cereal box.

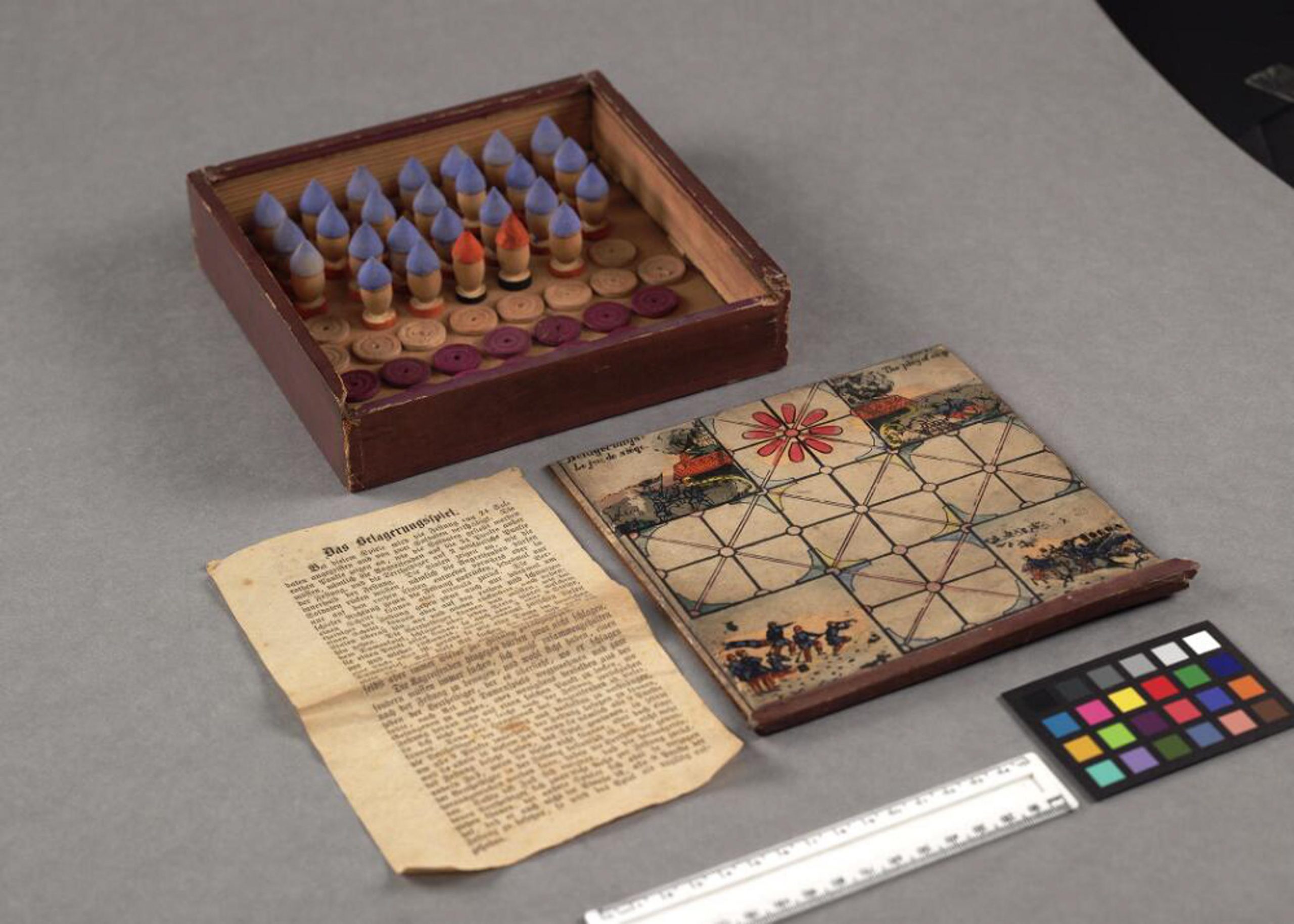

Around the same time a German board game, The Game of Besieging, became the first product to be available commercially, housed in a box. Contemporaneously, a pair of Boston watchmakers named Aaron and Eliphalet Dennison were sending their wares to jewellers in the area in small, rigid boxes. Tradesmen began to use these simple, rudimentary boxes made of strengthened paper to convey a wide range of goods, from cereals to silkworms.

That’s all well and good, but these small, fairly flimsy boxes are a world away from the strong, brown boxes that ship things across the world. Their story began not with a packaging company, but with a pair of English milliners: Edward Allen and Edward Healey.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

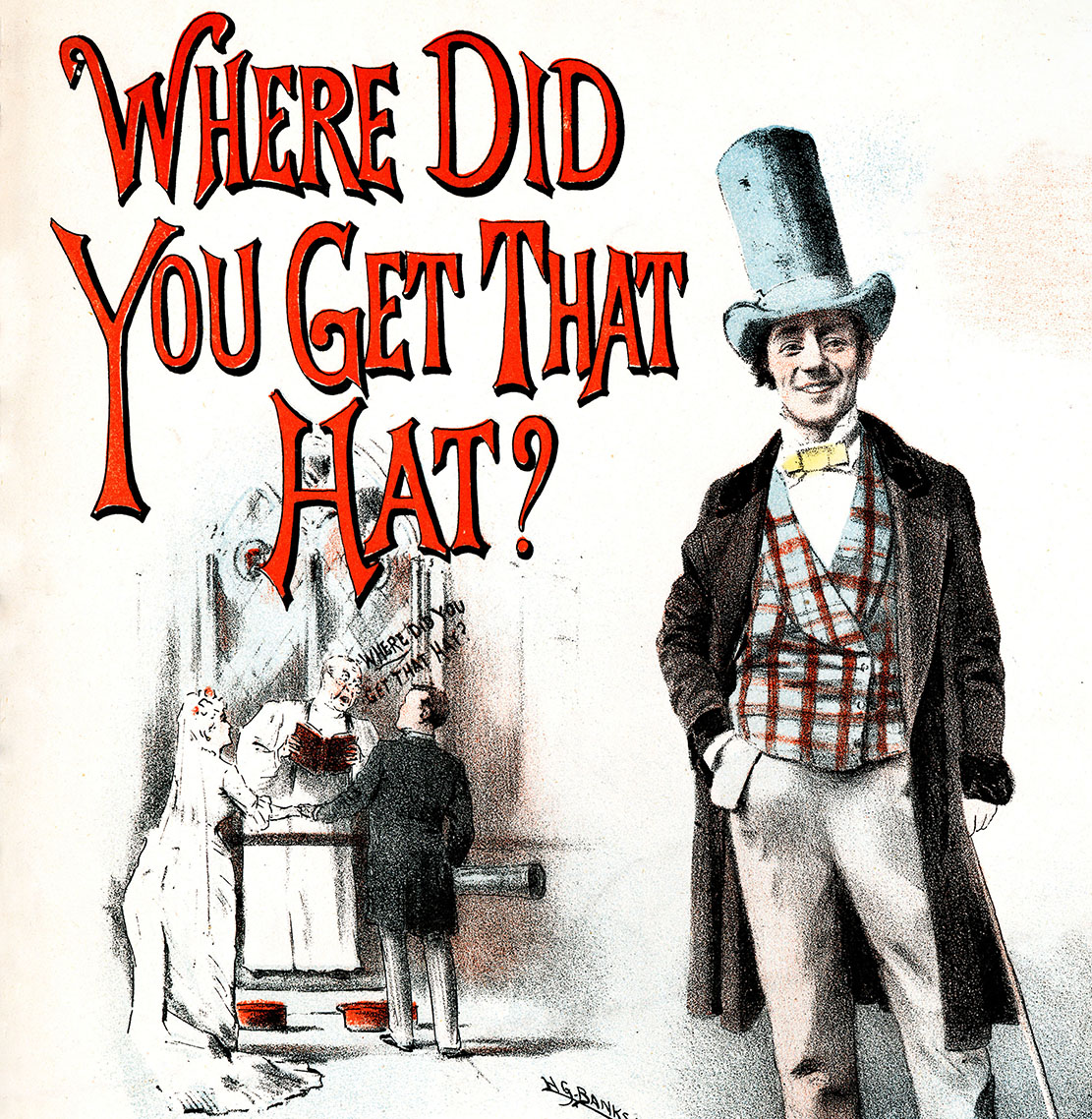

I have never worn one, but I am told that one of the problems with a top hat is how to ensure that it retains its shape, something that exercised the minds of Allen and Healey, and all their rivals. They came up with a solution to this seemingly intractable problem by designing a form of paper where a fluted middle was sandwiched between two linear boards. We would know it now as corrugated paper. It had an added benefit, insulating the hat and keeping the wearer’s head warm. The duo patented their invention in 1856 and this form of paper became a staple component of their toppers.

It took fifteen years for someone to realise that as well as giving rigidity to a hat, corrugated paper might also strengthen boxes. A New Yorker, Albert Jones, was awarded a patent in December 1871 for ‘improvement in paper for packing’. Concerned with protecting bottles, glass, and other fragile articles during transportation, he added corrugated paper to the inside of the box, either pressing directly on to the surface of the box’s contents or to another layer of cardboard inside the box.

Jones noted in his patent application that his invention was not just limited to the transportation of ‘vials’ but had wider applications and the innards of the box need not be restricted to cardboard. It is always a smart move to widen the appeal of your invention. Most cardboard boxes these days retain Jones’ original design, enhanced three years later, by Oliver Long who added a second flat liner to the pleated paper, giving it more flexibility while preserving its rigidity.

Creating a box out of a single piece of cardboard was a laborious and expensive process, requiring the sheet to be scored with a press and the use of a guillotine knife to make the necessary incisions. That is until a Brooklyn paper bag factory owner, Scottish-born Robert Gair, realised, in 1879, that he could raise the blades of the press and score and cut at the same time. This simple change, the result of an error by one of his operatives, who had cut through a batch of bags by failing to raise the press blade, transformed the rate at which the boxes could be produced. The age of the cheap, mass produced box was dawning.

Although manufacturers used Gair’s boxes, it was mainly for small items such as tea and tobacco. German chemist, Carl F Dahl, put the final piece in the jigsaw, when he developed Kraft paper, made from pulped pine wood chips and impressively elastic and tear resistant. Kraft, meaning strong in German, was patented in 1884 and so game-changing was it that within two decades paper mills throughout the world were producing it.

Gair switched to using Kraft paper in conjunction with corrugated card in 1896, a change that had a significant transformation on production figures. In the space of 2.5 hours he could produce what his factory had previously taken a day to manufacture, reducing the unit cost of pre-creased, pre-cut cardboard boxes to affordable levels. His investment was almost immediately rewarded, the National Biscuit Company placing an order for two million boxes, allowing their products to be sold in wax-paper lined boxes. This ensured that the biscuits remained fresh, removing the need for a shop assistant to fish them out of a damp and unhygienic cracker barrel.

Since then the cardboard box’s design has barely changed. Instead the focus has been on innovation in use. From 1938 the Finnish government has given mothers-to-be a maternity package, consisting of bodysuits, a sleeping bag, outdoor gear, bathing products, nappies, bedding, and a small mattress, all in a cardboard box. The scheme was intended initially to assist those on a low income but was extended in 1949 to all mothers and still runs today. The box and mattress double up as a crib and many a young Finn has taken their first nap surrounded by cardboard.

In May 2020, a Colombian design company announced that, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, it was producing hospital beds out of cardboard which could then be used as coffins. The advantage, they claimed, was the now deceased patient’s body did not need to be moved, thus reducing the risk of transmission. The cardboard box truly does offer a cradle to grave service.

Credit: Photo by FLPA/Hugh Lansdown/REX/Shutterstock – Bullet Ant (Paraponera clavata) adult, standing on leaf in rainforest, Tortuguero N.P., Limon Province, Costa Rica

Curious Questions: What is the world’s most painful insect sting – and where would it hurt the most?

Can you calibrate the intensity of different insect stings? Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions', investigates.

Credit: Rex

Curious Questions: Why do we still use the QWERTY keyboard?

The strange layout of keyboards in the Anglophone world is as bafflingly illogical. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Curious Questions: What is the perfect hangover cure?

If there's a definite answer, it's time we knew. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions', investigates.

Credit: apples and oranges Photo by Best Shot Factory/REX/Shutterstock

Curious Questions: Can you actually compare apples and oranges?

It's repeated so often these days that we've come to regard it as a truism, but are apples and oranges

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.