Curious Questions: When was the world’s first motor show held?

May 9 marks the anniversary of what many have regarded to be the first motor trade show; but was it really the first motorcar show, wonders Martin Fone?

We take the motor car so much for granted that it is hard to imagine at this distance how transformational and liberating a form of transport it would have seemed in the last decade of the 19th century.

It offered the very real prospect, albeit for those who could afford it, the opportunity to travel where they wanted, at speed, and without the constraints imposed by the stamina of a horse or the vagaries of the railway timetable.

What better way for the early enthusiasts of these new-fangled machines to demonstrate their practicality than through an organised public event?

And so, the idea of the motor show was born.

May 9th this year (2021) will mark the 125th anniversary of what many have regarded to be the first motor trade show.

Organised by the recently established Motor Car Club, it marked the opening of the summer season of the Imperial Institute in London and ran for three months until August 8, 1896.

The future Edward VII, then Prince of Wales, made an ‘informal visit’ on the opening day of what was called ‘The International Horseless Carriage Exhibition’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the magazine Autocar, in its review on May 16th that year, thought that the descriptor ‘autocar’ was ‘much neater and more applicable than that employed in the title of the show’.

Nevertheless, they were fulsome in its praise, commenting that it ‘is really one that should not be missed by any person feeling even a passing interest in the road, pleasure and business vehicle of the near future’.

The exhibition brought together ten different makes of motor car and motorcycle and offered the visitor the opportunity ‘to make trial of some of the motor cars, which are manoeuvred on the ground’.

The hot topic at this exhibition was what was the optimal form of propulsion, a debate that resonates today. Autocar reported that the purchaser of the near future ‘will have to choose between oil and electricity as a source of power’.

The Universal Electric Carriage Syndicate claimed that its vehicle could travel some thirty-five to forty miles at eight miles per hour without recharging, an operation that lasted three hours.

Conversely, a vehicle displayed by the Arnold Motor Carriage Co, fuelled by benzoline, could travel seventy miles at the cost of a halfpenny a mile, yours for ‘about £125’, twice the average annual wage at the time.

Autocar concluded that ‘electricity has the advantage that it works without smell and with less noise and vibration, but the disadvantage of the costliness of the accumulators, and the impossibility of recharging except where the electric supply is available’.

As we know, cost and convenience won out.

The exhibition also included a display of flying machines, including a model of Mr Maxim’s steam-powered flying machine, a replica of Otto Lilienthal’s glider, in which he was to meet his death later that year, and one which used two small balloons to take off.

Such was the interest that by the turn of the century there were three annual motor shows in the London area alone.

Was it the first motor show, though?

Galling as it may seem, the French were quickest off the mark, holding, on December 11, 1894 on the Champs-Ėlysées, the grandiloquently named Exposition Internationale de Velocipedie et de Locomotion Automobile.

There were nine vehicles on display from four manufacturers. One interested visitor was Sir David Salomons, who, mortified to see that the French had stolen a march, was determined, according to an interview in The Sketch, that English manufacturers should produce a ‘carriage which will eclipse all others’.

His visit to Paris was the catalyst for the emergence of the British car industry.

As mayor of Tunbridge Wells, Salomons saw an opportunity to put his town on the motoring map by organising a show along the lines of that in Paris.

It was held at the town’s Agricultural Show Ground in the autumn of 1895, with just five vehicles on display, none of which, to Salomon’s chagrin, were British made.

His own exhibit was a Peugeot, which followed the familiar horse carriage vis-à-vis design, where the passengers sitting at the front travelled backwards looking at the driver perched on a raised seat at the rear. Tall hats were not welcome!

To put Salomons’ initiative into context, it was only on July 5 that year that the first substantial road trip was made in England.

The Honourable Evelyn Ellis picked up his newly imported Panhard et Levassor at Micheldever and, with Frederick Simms as passenger, drove to his home in Datchet, a journey of 56 miles.

It took five hours and 32 minutes, excluding stops, at a law-breaking average speed of 9.84mph. Wherever they stopped, they drew a crowd of onlookers and as they travelled through the countryside, the vehicle was ‘an object of a great deal of curiosity’. It was the star of Salomons’ show.

Ellis, the first Englishman to pass a driving test, in Paris in 1895, forty years before it was made compulsory here, also displayed a fire engine which, without a ladder, was little more than a motorised water pump.

A motorcycle and a noisy, fire belching ‘steam horse’ completed the exhibits. Still, from little acorns grow mighty oaks.

It was, in part, thanks to Salomons that the roadblock to motoring that was the Locomotive Act of 1865 was removed.

This legislation imposed a speed limit on all self-propelled vehicles of four miles per hour in the countryside and two miles an hour in towns and required that someone carrying a red flag walk ahead of the machine to warn oncomers of its advent — a red rag to any aspiring motorist and cheerfully ignored by some, not least Ellis.

With Simms, Salomons founded the Self-Propelled Traffic Association in December 1895 and launched a vigorous campaign against the Act.

Despite the two protagonists falling out and Simms forming a rival organisation, the Motor Car Club, their lobbying was successful.

A new Act, The Locomotives on Highways Act, 1896, removed the necessity for the red flag and increased the maximum speed limit over threefold to a heady fourteen miles an hour. It was full steam ahead for the self-propelled vehicle.

On the day that the Act came into force, November 14, 1896, the Motor Car Club organised an Emancipation Run.

At a breakfast held at the Charing Cross Hotel, Lord Winchelsea ceremonially tore a red flag in two.

Then, from 10.30 am onwards, thirty-three motorists set off from the Metropole Hotel, on the corner of Northumberland Avenue and Whitehall Place, to Brighton, sent off on their way by a ‘flying escort’ of cyclists, numbering, according to one contemporary report, ‘probably 10,000’.

Between thirteen and nineteen completed the course, reports vary, although there were allegations that some were taken down to Brighton by train, splattered with mud and then driven to the finishing line.

Salomons and Simms buried the hatchet the following year, merging their two organisations to form the Automobile Club, later to become the Royal Automobile Club. Motoring had arrived via Paris, Tunbridge Wells, and the Imperial Institute.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwards

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwardsCampaigners in England often point to Scotland as an example of how brilliantly Right to Roam works, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, says Patrick Galbraith.

By Patrick Galbraith

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

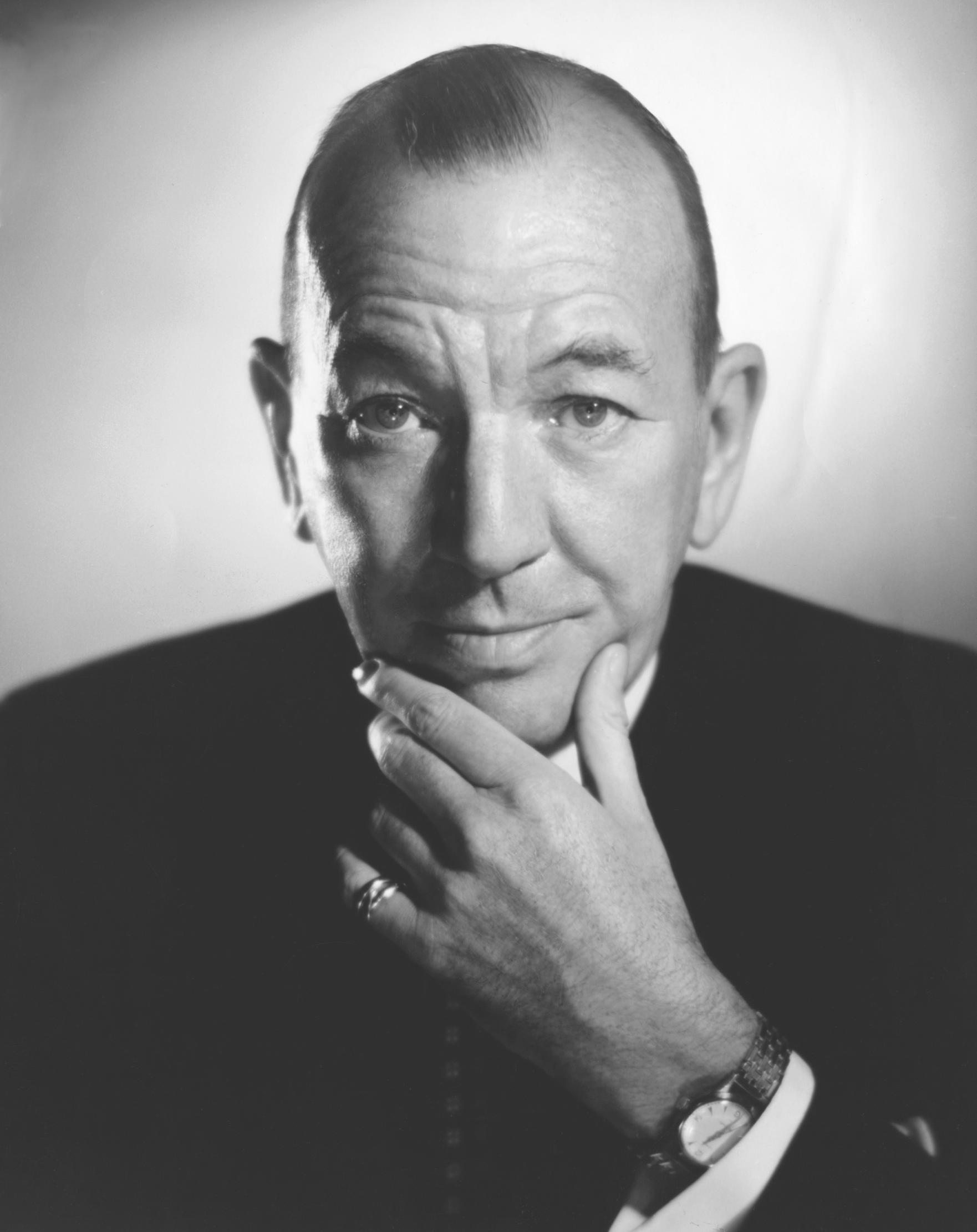

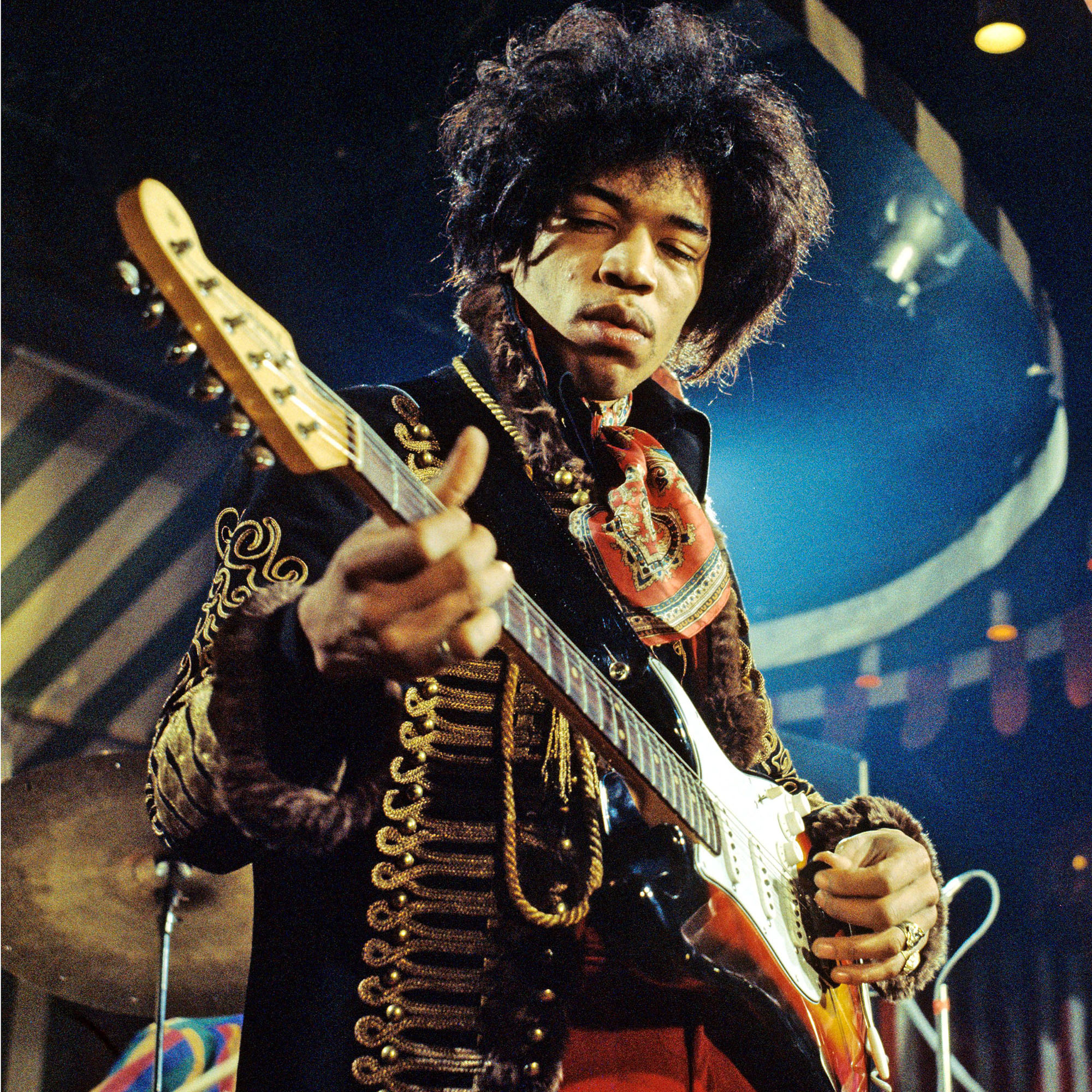

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.

By Martin Fone