Curious Questions: When did the first passenger jet take off?

'Nowadays we travel to all parts of the globe, often within a day and often without changing planes,' says Martin Fone, as he muses on the birth of commercial air travel exactly 70 years ago.

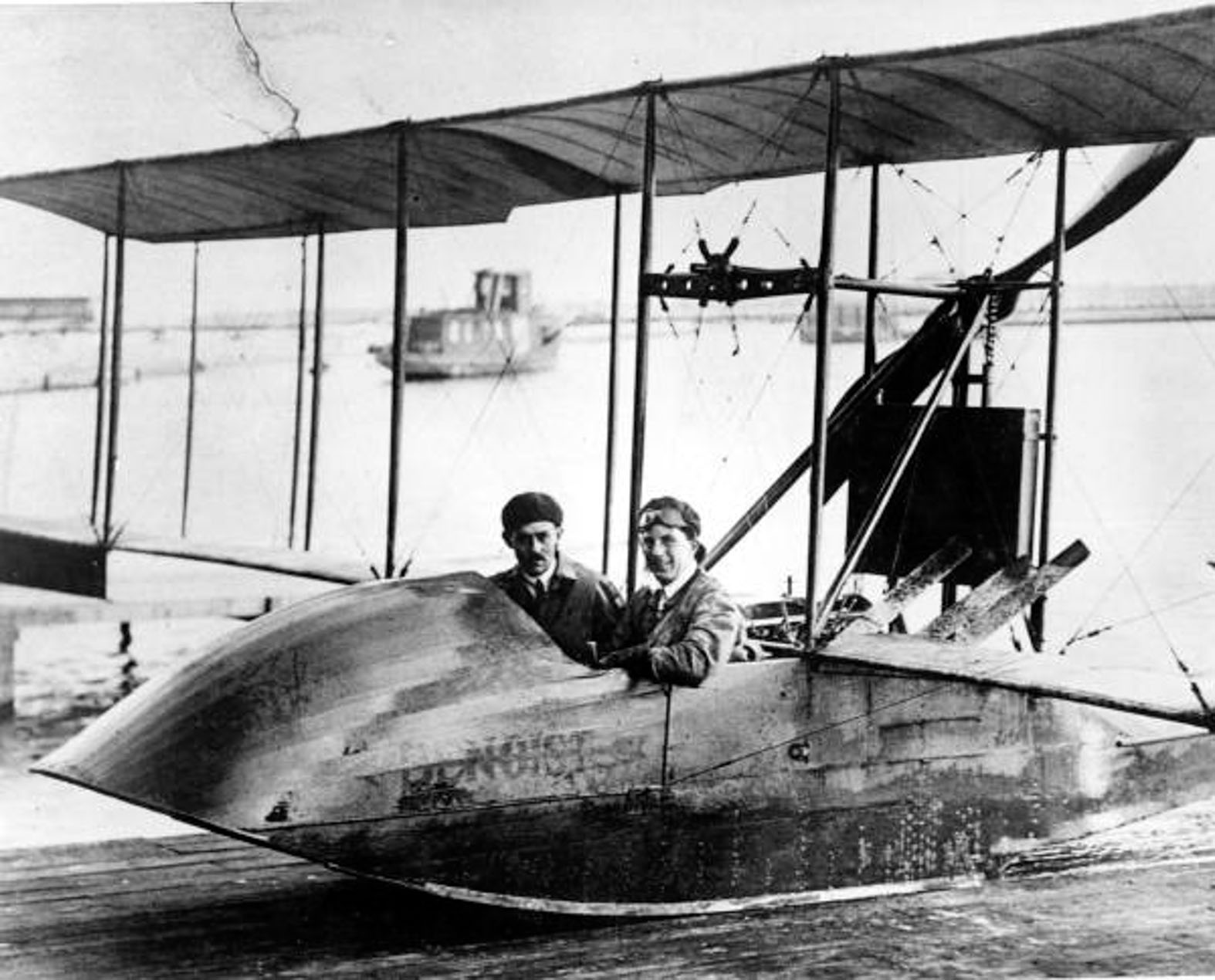

It was New Year’s Day, 1914. A crowd of 3,000 spectators, having paraded through the streets of St Petersburg in Florida to the accompaniment of what the local newspaper described as an Italian band, gathered at the waterfront. At an impromptu auction a former mayor, Abram C Pheil, paid $400 to become the first paying passenger on the inaugural flight of the St Petersburg-Tampa Airboat line. He clambered aboard the wooden flying boat, a Benoist XIV, joining the pilot, Tony Jannus, in the open-air cockpit.

The plane took off and completed the seventeen-mile journey across the bay to Tampa in twenty-three minutes, barely rising more than five feet above the water. Commercial aeroplane travel was born. Charging $5 for a one-way ticket and $5 per hundred pounds of freight, the airline carried 1,205 passengers and made 172 flights before it ceased trading on May 5, 1914.

Reflecting on the short life of the St Petersburg-Tampa Airboat line, Thomas Benoist, the plane’s designer, prophesied that ‘someday people will be crossing oceans on airliners like they do on steamships today’. He was not wrong. In 2019, before the pandemic struck airlines carried 4.5 billion passengers, a staggering figure. Even in 2021 as the world made its first cautious steps to recovery, 2.2 billion passengers took to the air and the numbers this year are set to soar.

Benoist’s flying boat, though, was not the first successful commercial passenger aircraft. That honour goes to the Schwaben, a German rigid airship, which made its first commercial flight on July 16, 1911. It could carry twenty passengers, all of whom were accommodated under cover, and from March 1912 enjoyed the services of Heinrich Kubis, the world’s first air steward. On June 28, 1912, the airship was destroyed after breaking from its moorings in an airfield near Dusseldorf during a gale. By that time, it had made 218 flights and carried 1,553 passengers.

Between the two World Wars, aircraft technology advanced by leaps and bounds, extending the reach and capacity of planes, and making passenger flight commercially viable. The biggest challenge was to find a way to cross the Atlantic, notorious for its bad weather and lack of suitable stopping points. Boeing’s B-314 flying boat, a double-decker with a range of 3,500 miles and able to carry seventy-four passengers, rose to the challenge, enabling Pan American to run the first transatlantic passenger flight between New York and Marseilles on June 28, 1939. Passengers paid $350 for the privilege of crossing the Atlantic more quickly than sailing by liner.

Nowadays we travel to all parts of the globe, often within a day and often without changing planes, barely giving a thought to the technological developments that make this possible. What revolutionised air travel was the jet engine, which enabled aircraft to travel further, and faster, climb faster and fly higher, than planes powered by piston engines. It was the prospect of war and the desire to gain an advantage over the potential enemy rather than commercial forces that drove these advances in aircraft technology.

As with commercial air travel, Germany was quickest off the mark, Hans von Ohein building the first experimental jet plane, a Heinkel He 178, which made its maiden flight on August 27, 1939. Anselm Franz improved upon the design to create an engine suitable for use in a jet fighter. A Messerschmitt Me 262, flown by Alfred Schreiber, was the first jet fighter to be used in active combat, attacking an RAF de Havilland Mosquito on July 26, 1944, but failing to shoot it down.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Due to its high fuel consumption, the German jet spent much of its time on the airfield, making it an easy target for Allied air raids. Meanwhile, in England Frank Whittle had independently invented a jet engine, a version of which was used to propel the Gloster Meteor. Used primarily for defensive purposes due to its lack of speed, the Gloster scored the world’s first jet on jet aerial victory when Flying Officer Dean shot down a V-1 flying bomb on August 4, 1944.

Curiously, though, once war had ended commercial airlines were slow to take advantage of the possibilities offered by the jet engine. There were several reasons, some of which presaged the troubles that dogged early commercial jet planes. Although jet engines were simpler than piston engines, they needed to operate at considerably higher temperatures, which meant that more expensive metal alloys had to be used, which at the time were notoriously unreliable. Heavy fuel consumption increased operating costs and the jet’s lower take-off speeds meant that runways had to be extended.

Someone had to grasp the nettle and it fell to aviation veteran, Sir Geoffrey de Havilland to make the first move. Inspired by the Wright brothers, he had made and piloted his first aeroplane in 1910, established the company which bore his name in 1920, and during the Second World War designed several fighter planes, for which he was knighted in 1944. Once the war had ended, he turned his attention to jets, designing the Comet and the Ghost engine, the first de Haviland Comet making its inaugural test flight on July 27, 1949.

It took almost three more years of testing before the aeroplane was deemed to be ready to make its first commercial flight. On May 2, 1952, the third Comet ever built, registered as G-ALYP, took off with forty-four passengers on a British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) scheduled flight from London to Johannesburg. The route was carefully chosen, allowing the plane to make stops at Rome, Beirut, Khartoum, Entebbe, and Livingstone, near Victoria Falls and fly mainly over land.

It was declared a success, passengers noting that the aeroplane was quieter and did not vibrate as much as planes propelled by piston-engines. With a cruising speed of 480 miles per hour, it was more than two and a half times faster than the most well-known piston-engine aircraft, the DC-3. The age of commercial jet travel had arrived.

Problems, though, dogged the Comet. The pioneering G-ALYP was one of the first commercial jet airliners to be lost when on January 10, 1954, after taking off from Rome on the last leg of BOAC’s scheduled flight from Singapore to Heathrow, there was an explosion. The plane crashed into the Mediterranean near Elba. killing all twenty-nine passengers, ten of whom were children, and its six crew members. Their fatal injuries of fractured skulls and ruptured lungs were consistent with the investigators’ findings that the plane had suffered metal fatigue caused by repeatedly pressuring and de-pressurising the cabin.

After another fatal crash, the Comet was grounded and it took a further four years before a modified version satisfied the regulators that it was safe to operate commercially, by which time American airline manufacturers, Boeing and Douglas, had cornered the market with their more efficient jets.

Today, air travel is the safest mode of travel with just 0.07 deaths per billion passenger miles, a statistic which seventy years was just a pipe dream. Air travel has certainly come a long way since then.

Credit: Getty Images/AWL Images RM

Gstaad, Switzerland: ‘The last paradise in a crazy world’, a fairytale still untouched with pistes aplenty

Rosie Paterson travels to Gstaad–once described by Julie Andrews as ‘the last paradise in a crazy world’– to find out

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Tanzania and the Seychelles: The ultimate surf-and-turf holiday, from pristine beaches and giant tortoises to rolling planes of migrating wilderbeast

Africa is home to some of the most diverse flora and fauna in the world. Mark Hedges jets off on

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.