Curious Questions: When and why did we start bathing in the sea?

Despite the British love of seafaring, voluntarily taking a dip in the sea was almost unheard of until relatively recently. Martin Fone takes a look at how a bit of canny marketing helped change that.

In 1626, about half a mile south of the harbour at Scarborough, Mrs Farrow spotted a spring trickling out of the cliff. Curious, she tasted the water and found that it had an acidic taste and ‘opened the belly’. She took the waters regularly herself and prescribed it to her friends when they were ill. It seemed to make them feel better. Word of its health-giving properties soon got round, attracting ‘persons of quality’ to the North Yorkshire coastal town to take the Scarborough spaw.

Dr Robert Wittie, a physician from Hull, was an advocate of it, claiming that ‘it cleanses the stomach, opens the lungs, cures asthma and scurvy, purifies the blood, cures jaunders, both yellow and black, the leprossie and moreover a most sovereign remedy against hypocondriack, melancholy and windiness’ (Scarborough Spa (1660)). Farrow’s discovery and Wittie’s boosterism put Scarborough firmly on the map, one of around forty-eight spas that were founded in England between 1660 and 1815.

Although the term ‘spa’ was not coined until after the discovery of natural Chalybeate springs in the eponymous Belgian town in 1326, the Romans had enjoyed the benefits of mineral-rich spring waters in places such as Bath and Buxton. The fortunes of Bath’s spa were revived when the local bishop, John Villula, had it rebuilt in 1088 and soon, according to Gesta Stephani (1138), it attracted ‘from all over England sick people’ who came to ‘wash away their infirmities in the healing waters’.

Temporarily banned by Henry VIII as a potential meeting place for Catholics, spas received a royal fillip when Elizabeth I, visiting Bath to grant it city status, declared that ‘the thermal waters should be accessible to the public in perpetuity’. She was an enthusiastic imbiber of the waters from Buxton and by the turn of 17th century taking the waters was a fashionable thing to do. Such were the low standards of personal hygiene, though, that attendants had to be employed to scrape the scum of the surface of the waters.

Rivalry amongst the spa towns was intense, but Scarborough quickly realised that it had a significant advantage; it was by the sea. Curiously, for an island nation dependent upon the sea for its economic prosperity, security, and its imperialistic ambitions, Britons were remarkably reluctant to step, never mind, plunge into it.

This all changed in the 18th century when physicians ‘discovered’ the medicinal benefits of sea water. It was seen as a purgative and a cure-all, with patients being prescribed lengthy courses of imbibing sea water, often as much as a pint a day over the course of six months. To make it more palatable, it was sometimes mixed with milk and, for those unable to get to the coast, was sold by the bottle.

Exposing the body externally to sea water was also thought beneficial with physicians advocating a dip in the sea as part of a patient’s health regime. Early morning dips were especially favoured as the sea was at its coldest. Dr Richard Russell’s mantra of ‘the sea washes away all the Evils of Mankind’ proved highly influential, especially amongst the upper classes. His practice, based in Brighton, transformed the once sleepy fishing village into a fashionable seaside resort.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

To maintain a healthy constitution, physicians recommended that men bathe daily for five minutes before breakfast while two minutes three times a week was enough for the ‘weaker sex’ and children. The coast also offered an attractive alternative to the tedium of everyday life, as the poet William Cowper noted in Retirement (1782); ‘but now alike, gay widow, virgin, wife,/ ingenious to diversify dull life,/ and all, impatient of dry land, agree/ with one consent to rush into the sea’. Offering both a mineral spa and the sea, Scarborough became one of Britain’s first, if not the first, seaside resorts by the early 18th century.

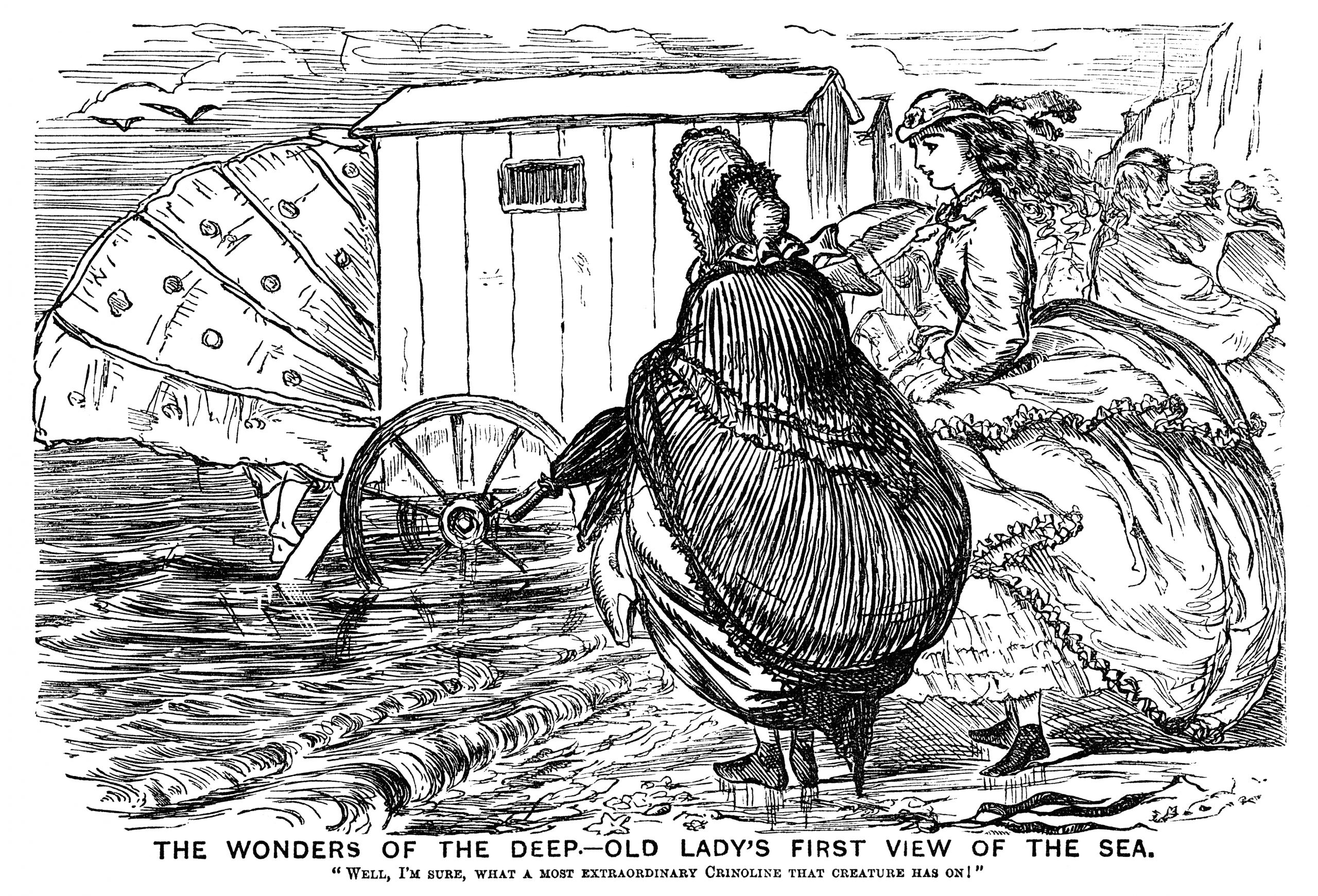

While men were able to bathe in puris naturalibus, a practice not banned until 1860, women, to preserve their modesty, entered the sea either fully clothed or in their voluminous undergarments. The idea of mixed bathing was contentious, many resorts adopting a prurient approach by segregating the beach and, by extension, the sea into men-only and women-only areas or imposing set times when one or other of the sexes could bathe.

A bathing machine provided a means for bathers to enter the sea with their dignity intact. John Setterington’s engraving of a beach scene at Scarborough from 1735, which can be seen at the town’s public library, shows an early example, a wooden hut on four wheels with a door at each end. According to Tobias Smollett (The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker (1771)), the bather climbed some wooden steps to enter the machine and undressed while a horse guided by the attendant pulled it to a point where the sea was level with its floor. The bather then plunged headlong into the sea, and when they had finished, clambered back on board to dry off, redress and be conveyed back to the shore. Benjamin Beale refined the design in 1750 by adding a large canvas hood, known as a tilt, which extended the rear of the machine.

A common sight on British beaches for the next 150 years, bathing machines cost six pennies to hire, plus a gratuity for the attendant. Once the bather had returned safely to the shore, the machine was hired out again, although later users would often find that the interior was wet and sandy. They only fell out of fashion towards the end of the 19th century, a recognition, to echo a correspondent to The Graphic in the 1870s, that ‘it is absurd that a house, a horse and an attendant are necessary to get someone into the sea’. By 1904 Scarborough had replaced them with bathing tents and the last were used in Margate in 1927.

From 1888 until 1914 Folkestone’s beach housed Walter Fagg’s patented bathing machine, two carriages, holding up to nine people each and equipped with clothes pegs, looking glasses, hat racks, wash basins, and even lavatories. Running along tracks sunk into the sand, the carriages were lifted in and out of the sea by a cable attached to a stationary steam engine.

The prospect of men and women in the sea still mortified many, one visitor to Scarborough fulminating that ‘mixed bathing is the halfway house to mixed sleeping and might be a plank on the river leading to the Niagara of eternal damnation’. Resorts vainly tried to impose standards, segregating beaches, and fining those who disregarded the byelaws.

An owner of a bathing machine at Lytham, according to The Preston Guardian of July 13, 1850, took three gentlemen down to an area reserved for females and received a fine of one shilling with costs of 9s.6d. for his troubles. With the railways bringing hordes of day-trippers eager to sample all that the seaside could offer, the authorities slowly began to realise that they were fighting a losing battle and most of the petty restrictions were abolished or allowed to lapse.

Apart from safety considerations, we are now free to enjoy the sea as we please. How times have changed.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.