Curious Questions: What is it like to sing at a royal coronation in Westminster Abbey?

The choristers at the Coronation are now in their eighties, but recall vividly the day they sang for The Queen, as Andrew Green discovers.

February 6, 1952. Young Malcolm Tanner was playing football at his Bristol school. ‘In the far distance,’ he recalls, ‘a teacher was making his way slowly towards us. He had words with our games master, who then came over and said: “Sorry boys, we’ve got to go in. The King’s died.” I have to say we were very annoyed at having to stop playing.’

At Westminster Abbey Choir School, James Wilkinson was in a Latin lesson when ‘we noticed the flag on Victoria Tower in the Palace of Westminster was at half mast. Then the headmaster informed us the King had died. My first reaction was one of excitement that there’d be new postage stamps and coins to collect.’

David Driscoll attended the King’s lying-in-state, making the pilgrimage to Westminster Hall together with fellow choristers from St Paul’s Cathedral. ‘I remember the solemn sight of soldiers stationed around the catafalque, heads bowed — and the silence. Extraordinary, with so many members of the public filing through.’

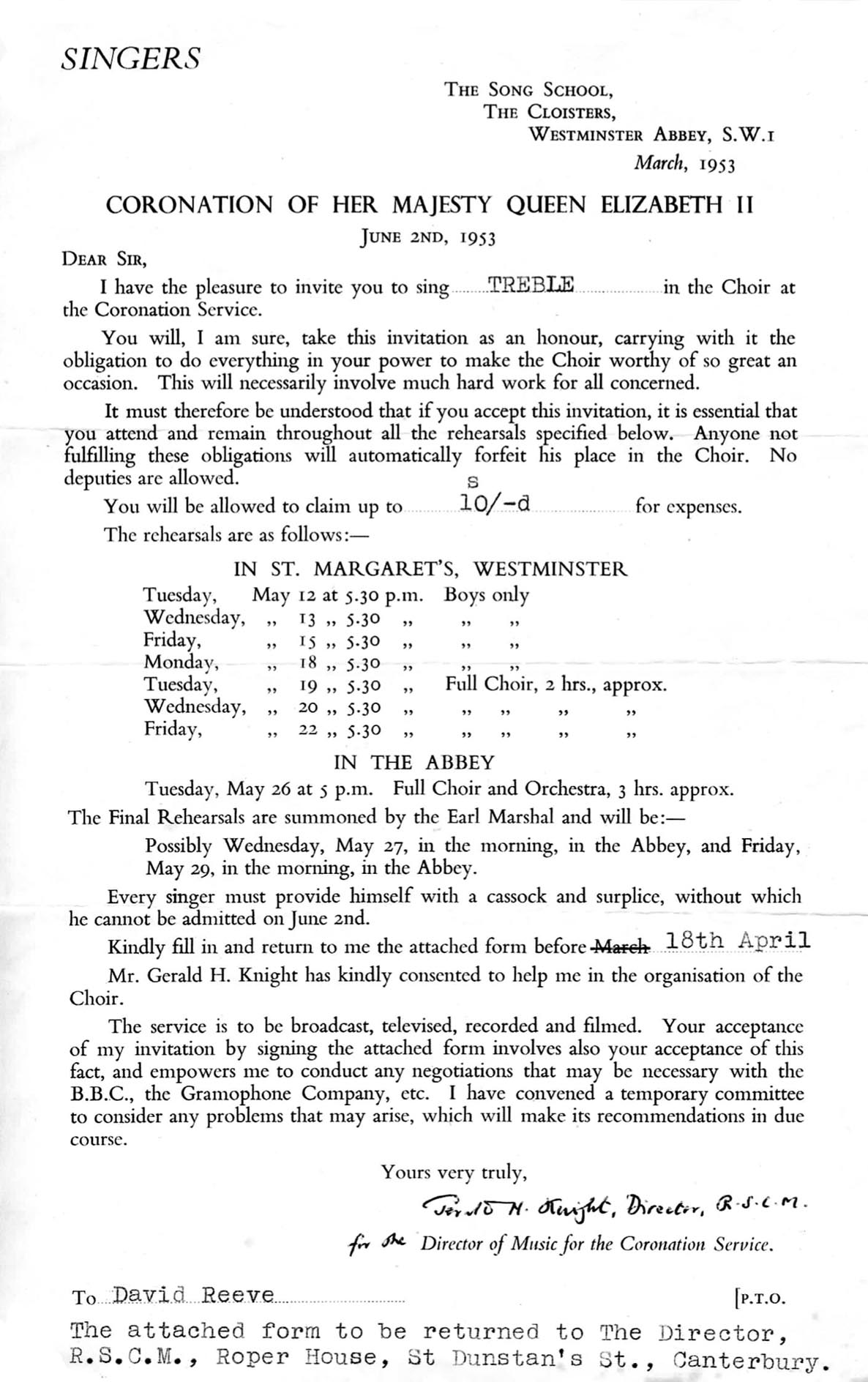

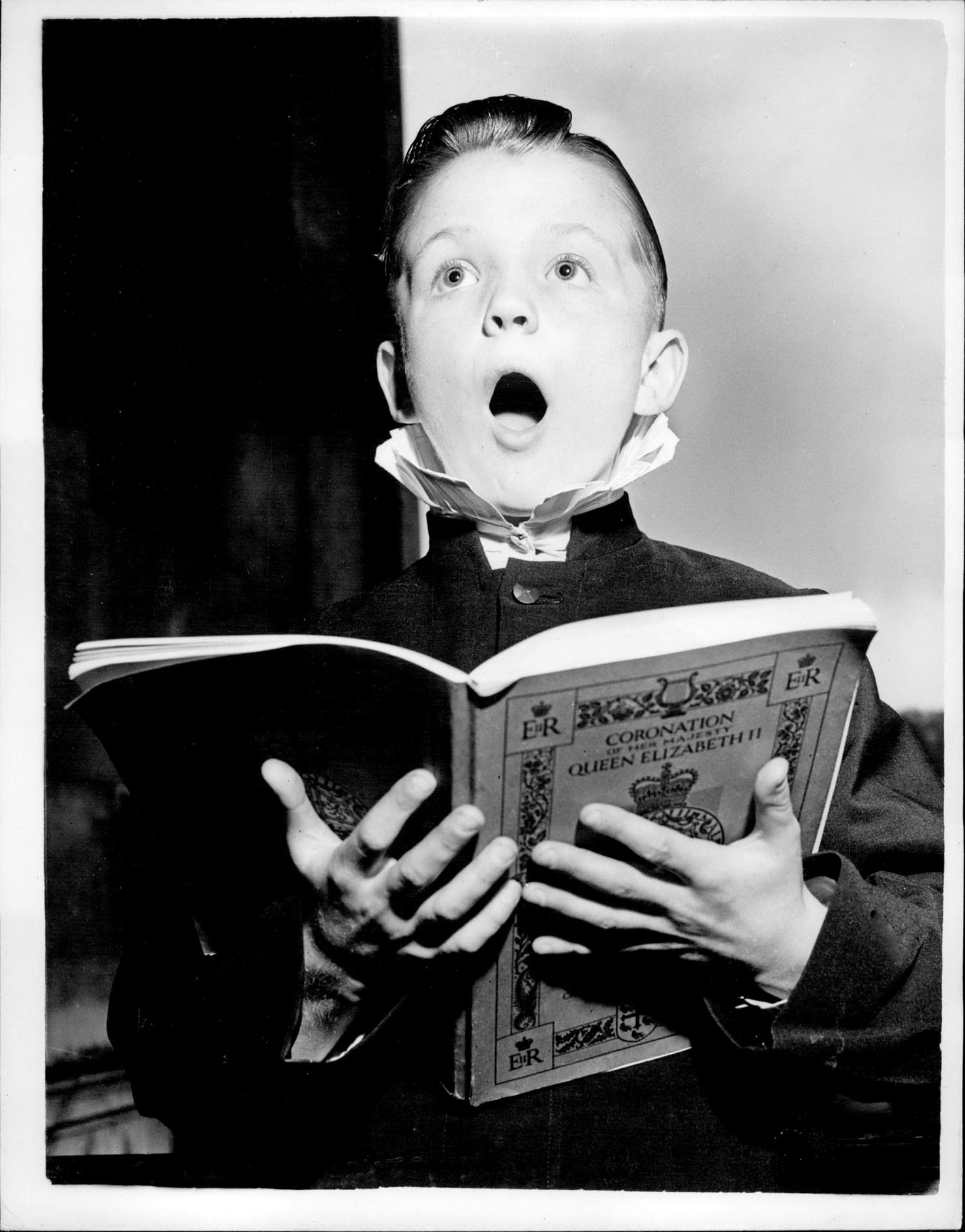

Each of these then choristers was to sing at the 1953 coronation, together with about 180 other boys, some selected from cathedral, chapel and church choirs that were affiliated to the Royal School of Church Music (RSCM), including Mr Tanner and Dennis Whitehead, then at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral in Edinburgh. Mr Whitehead still treasures his letter of invitation. ‘My parents were over the moon.’

News of selection often turned choristers into local celebrities, but Graham Neal’s good tidings had to be kept under wraps. ‘My mother couldn’t wait to tell the world, but it all had to be very hush-hush,’ relates the member of All Saints Church, Eastleigh, Hampshire. ‘I was at an age when my voice might have broken by the time of the coronation. What an anti-climax that would have been!’

RSCM-sponsored choristers had four weeks of rehearsals at the organisation’s Addington Palace HQ near Croydon, a month remembered for the intensity of the training, but also the array of sports that filled leisure time. Stanley Roocroft, from Blackburn Cathedral, recalls: ‘There was a golf course adjoining and a few of us older boys did caddying for some loose change. Word got back and we were sternly told it had to stop.’

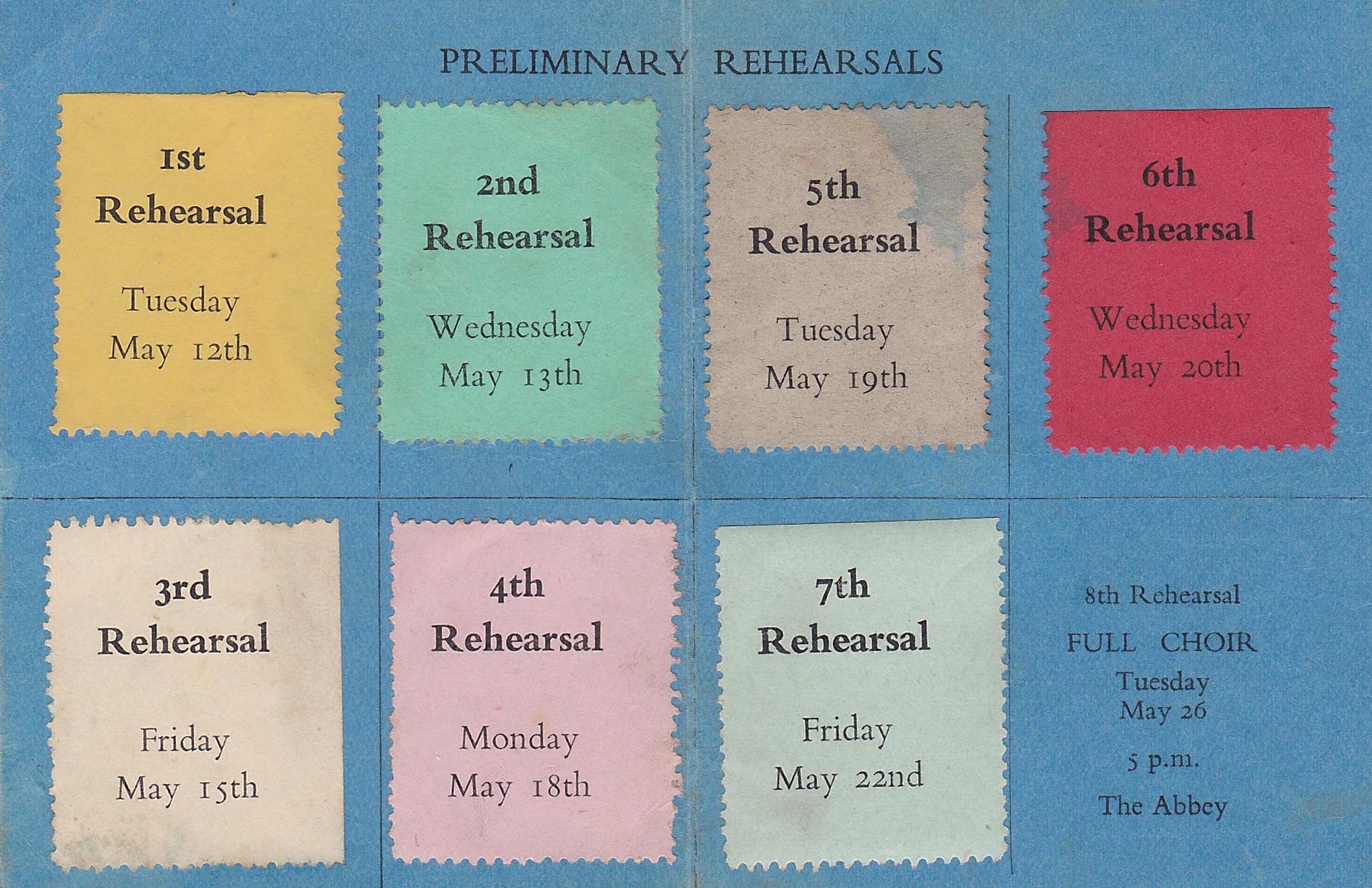

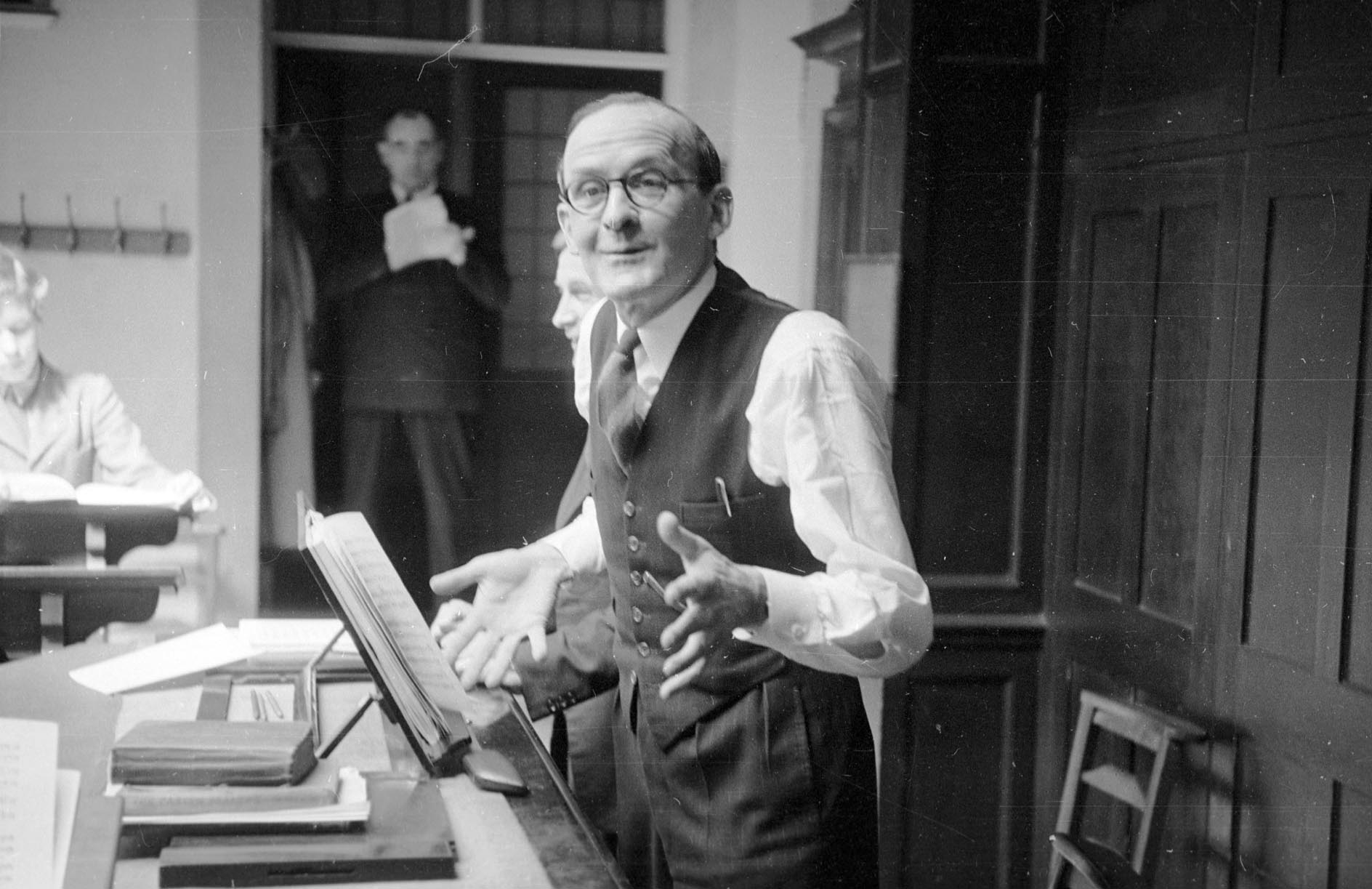

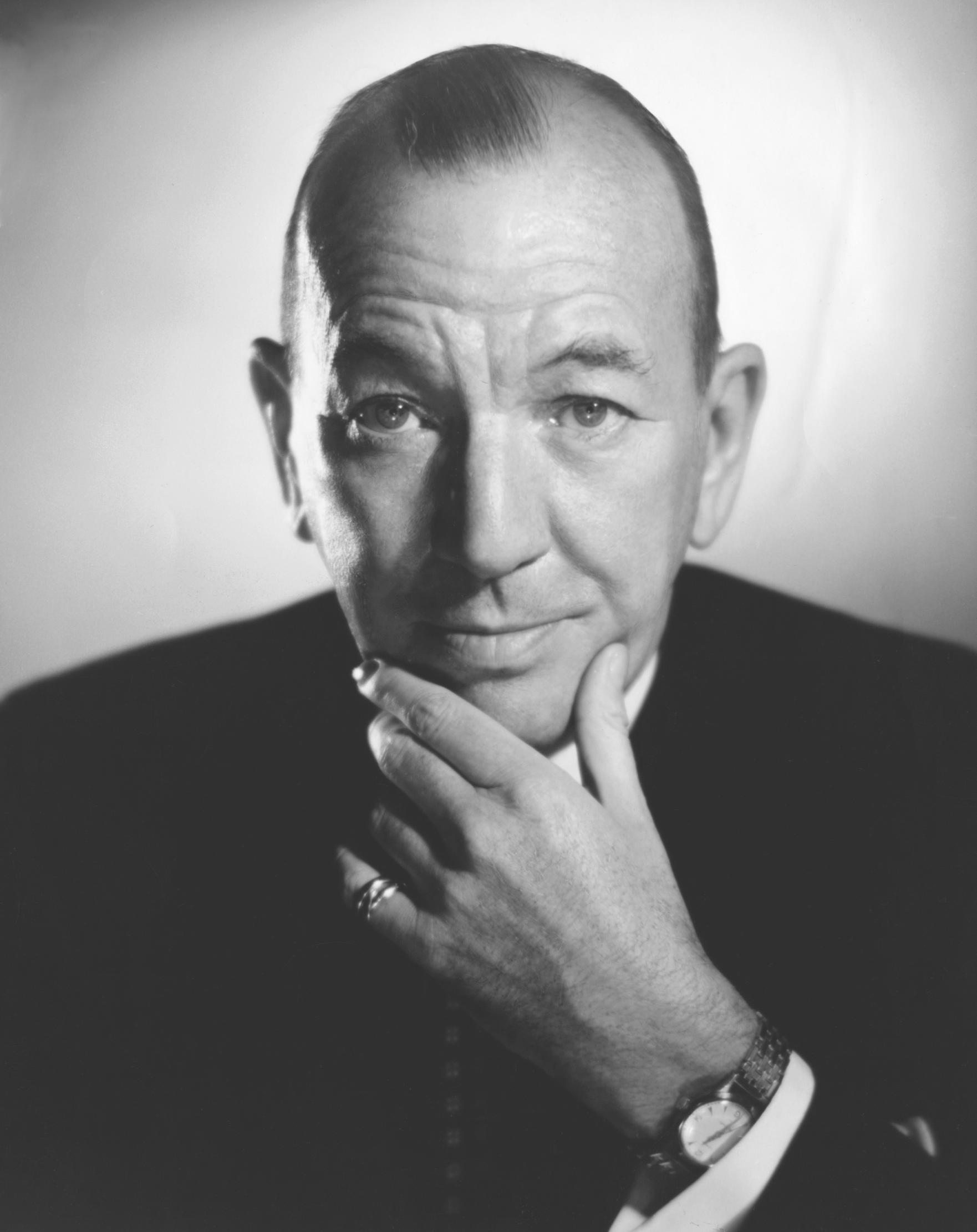

At last, the full choral forces — some 400 voices — gathered for final rehearsals, firstly at St Margaret’s Church, Westminster, then in the Abbey itself with full orchestra. The director of music, Abbey organist and choirmaster, Sir William McKie, insisted on ‘each musician bearing a card onto which were stuck stamps proving attendance at every rehearsal,’ explains David Reeve, from a school chapel choir in Norwich. ‘If you lost this card, you risked being sent home in disgrace.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

For Abbey chorister David Overton, it was his first sight of the building’s interior for months. ‘Normally, the building held 2,000. The banks of seating erected raised that to 8,000. It was exciting to see the Abbey transformed. And what a sound the musical forces now made! Spine-tingling!’

The full dress rehearsal brought further visual excitement. ‘The cameras filming the coronation needed additional light from powerful lamps — the Abbey was flooded with it,’ recalls Mr Wilkinson. ‘The colours of things such as robes, jewels and the nave carpet simply glowed.’

Afterwards, Field Marshal Montgomery lunched with the boys. ‘We had salad,’ Mr Wilkinson remembers, ‘and as Monty put his fork into a tomato it split and showered his ceremonial robes with juice and pips. A horrible hush descended, but he just looked at us and said: “See that, boys? Burst like a bomb!”’

It was an early start on June 2 for those who were travelling in from Addington Palace. ‘We were stirred at 4am by the Archdeacon of Maidstone calling out, “Wake up, boys. This is the day!”,’ Mr Roocroft recalls. The journey into London that damp morning landed the RSCM boys at Victoria, leaving a half-mile walk. Mr Neal describes: ‘The crowds were so thick on the pavements that we had to be conducted in a crocodile along the road, which was lined with flags, bunting, policemen and the armed services. You could see members of the public coming to and making cups of tea on Primus stoves.’

By 8.30am, the coronation choir was in place high up in the temporary seating. The long wait began. Attention soon turned to the packed lunches stowed in cassock pockets. Ham sandwiches and apples were polished off quickly. What to do with the apple cores? Drop them down the hollow scaffolding poles.

People-watching was the main pastime as the minutes crawled past. No tales of chorister transgressions, it seems, but a female singer from the Commonwealth and Dominions was reprimanded for getting out a morning paper. ‘I could make out Clement Attlee,’ remembers Mr Tanner. ‘I saw him give his wife a Horlicks tablet.

‘Winston Churchill entered wearing the robes of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. I’ve never seen anyone walk with such a roll and not fall over.’ And no one could forget Queen Salote of Tonga. ‘Big smile, colourful dress — a huge, flamboyant presence,’ is Mr Neal’s recollection. ‘She contrasted markedly with the rather dour Mr Nehru.’ Lord Wallace of Saltaire, then an Abbey chorister, recalls another light moment: ‘There came the sound of shuffling and people sprang to their feet. Who should appear, however, but women in overalls bearing carpet sweepers. Cue laughter, and we all sat down again.’

At last came The Queen’s appearance, greeted by Hubert Parry’s imperious anthem, I was glad. ‘The orchestral introduction gets you going, creates such tension,’ observes Mr Reeve. ‘Then at last, the opening phrase. Absolutely glorious!’ ‘I was so overcome that for a few seconds I couldn’t get the notes out,’ Mr Whitehead admits. ‘We were to keep our eyes absolutely glued to the conductor, of course,’ reports Mr Roocroft. ‘But we all had a sneak look at The Queen. Her appearance was just wonderful.’

At home, choristers’ parents were glued to new-fangled television sets, the coronation having prompted a massive boost in sales to a previously sceptical public. Viewers’ rights were soon being asserted. ‘My father actually rang up the BBC to complain that there were no shots of the choir,’ says Mr Wilkinson. ‘It was explained to him that there were only four cameras and none of them could be trained on the choir.’

Some choristers were in a better position than others to witness the climactic moment. ‘What surprised me,’ says Mr Wilkinson, ‘was that the Archbishop of Canterbury raised the crown so high above The Queen’s head before lowering it really slowly. Then came the shouts from the whole congregation of “God Save The Queen, Long Live The Queen, God Save The Queen”. I’d been expecting a great roar like a football crowd, with spontaneous cheering, but it started hesitantly and ended up as a rather polite unison.’

‘Children back then weren’t brought up to express their feelings,’ observes Mr Reeve, thoughtfully. ‘Listening to my recording brings back all the memories and somehow makes me more emotional than I felt at the time.’

Curious Questions: What is a jubilee?

The celebration of HM's Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee is imminent — but what is a jubilee, and where does this

The Queen's Corgis: All about Her Majesty's most loyal subjects

As we mourn the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, we take a look at her corgis, the dogs that were

The Queen's official portraits: Seven of the most extraordinary paintings from 70 years and over 1,000 sittings

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II has been painted literally thousands of times since she came to the throne. Charlotte Mullins

The anniversaries to look out for in 2022, from Ferdinand Magellan to Harry Potter, and from The Beatles to Carter unearthing Tutankhamun

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone

-

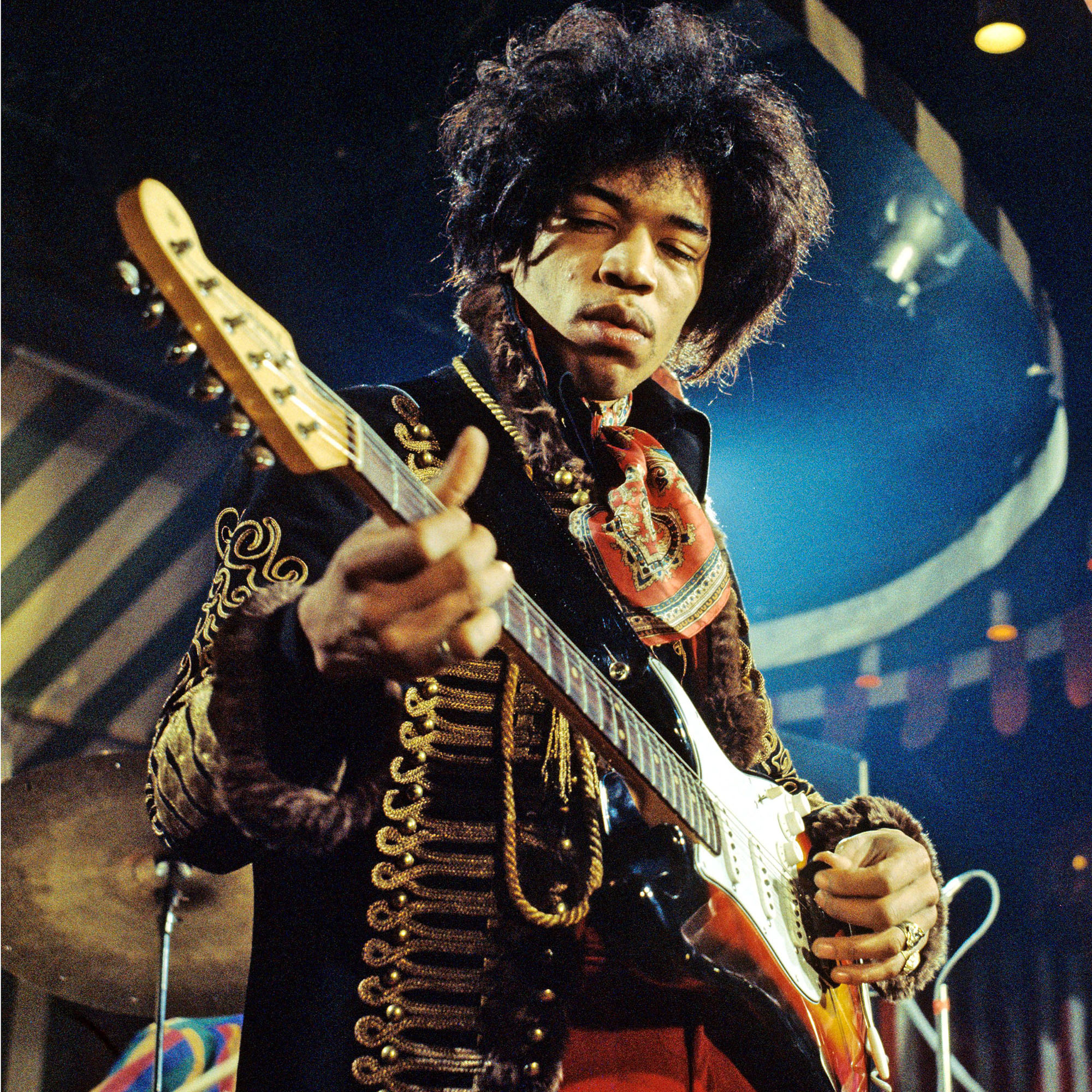

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.

By Martin Fone