Curious Questions: What is a tin tabernacle?

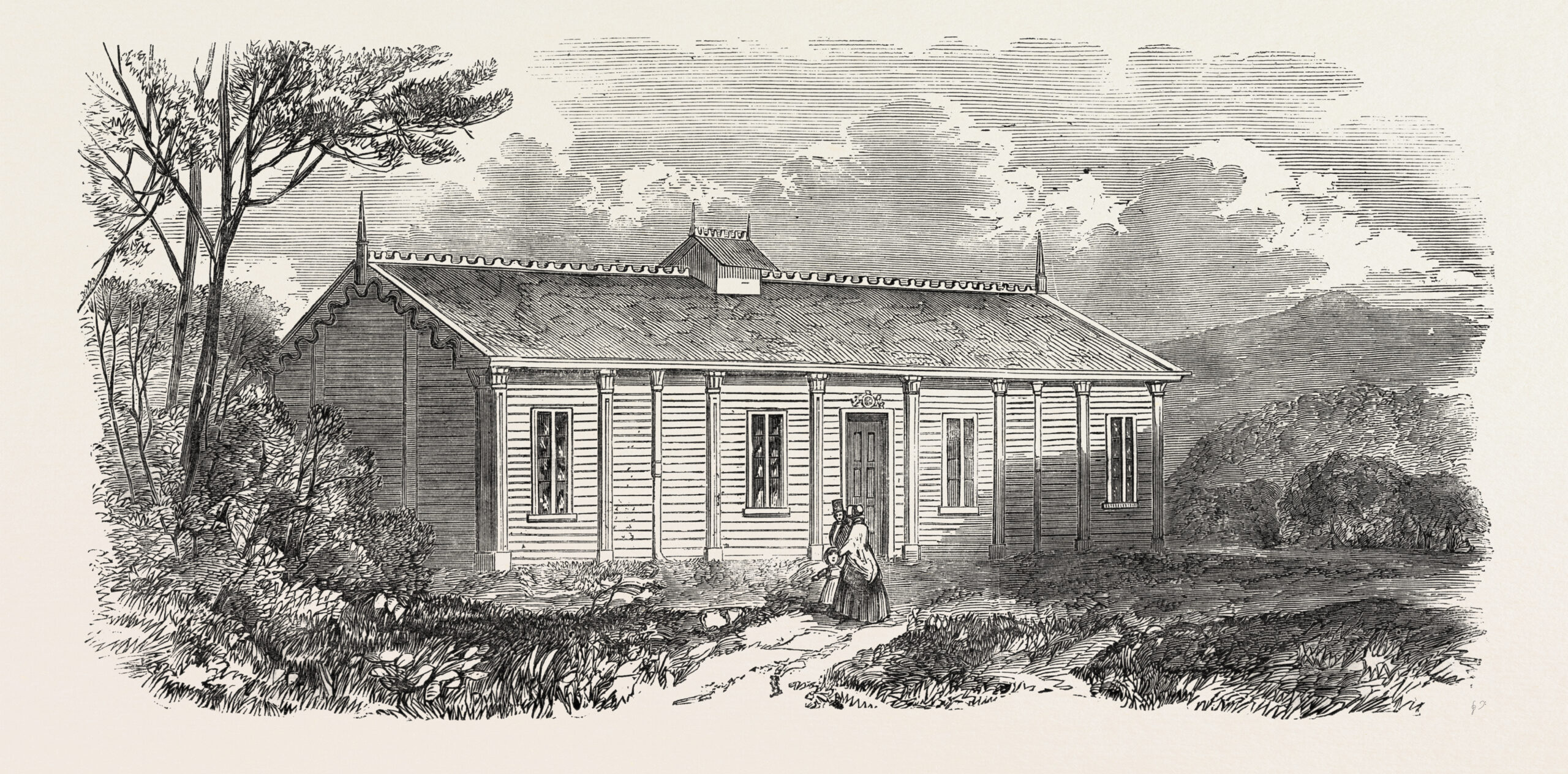

Martin Fone looks at the history of the tin tabernacle, and discovers a tale about the origins of corrugated iron, the history of the church in Britain and how Queen Victoria's ballroom at Balmoral got turned in to a joiner's workshop.

The open-sided turpentine shed built around 1830 as part of the extension to the London Docks was praised by contemporaries for its elegance, simplicity, and elegance. What was particularly notable was its roof, described by one commentator as ‘the lightest and strongest roof (for its weight) since the days of Adam’. Built from a material which Henry Palmer called in his April 1829 patent ‘indented or corrugated metallic sheets’, it was the first building to use what we now know as corrugated iron.

While ideal for roofing buildings with large spans, there was one problem: the corrugated sheets were made from wrought iron and quickly corroded. By 1837, though, a French engineer, Stanislav Sorel, had devised a method of coating the iron’s surface with a layer of zinc, thus dramatically increasing the resistance of the iron to corrosion and immediately transforming it into a long-lasting material.

The process of galvanization was introduced to Britain and patented by Commander HV Craufurd RN, who is credited with erecting the world’s first galvanized buildings: the storage sheds at Pembroke Docks erected in 1844. Palmer’s patent expired in 1843, sparking a boom in corrugated iron production using a technique still deployed today, passing red-hot sheets of wrought iron through a rolling mill, not dissimilar to a mangle with interlocking rollers.

The use of corrugated iron to produce prefabricated buildings of all shapes and sizes soon caught on and royal patronage helped. Prince Albert ordered a corrugated iron ballroom for Balmoral estate. It still stands to this day, making it almost certainly the oldest surviving metal sheet building in the world — though it’s now a joiner’s workshop (you can take a look inside at this BBC video). Although the rash of buildings were pejoratively known as tin buildings, there is no evidence to suggest that anything other than zinc was used to coat the iron.

Timing is everything and the new material was seen as an answer to a problem caused by the dramatic sociological changes Britain was undergoing, the diaspora from countryside to town and the increasingly fissiparous nature of the established churches. With churches using the traditional materials espoused by the Ecclesiological Society taking too long to build and being too expensive for new congregations to contemplate and existing churches either in the wrong place or too small to accommodate the burgeoning communities, corrugated iron structures seemed to be the obvious solution.

A major ecclesiastical schism, the ‘Disruption’ of 1843 in Scotland, led to the secession of a third of the clergy and congregation from the Church of Scotland to set up the Free Church of Scotland. Many of the local landowners, like Sir James Riddell of Arnamurchan, sought to suppress the upstart church by refusing permission to build places of worship on their land.

In response the Free Church commissioned, at a cost of £1,400, the Port Glasgow firm of John Reid & Co to build an iron ship on top of which was erected a large shed capable of holding up to four hundred people. In June 1846 the ship was towed to Ardnastang Bay, near Strontian on Loch Sunart, and anchored just 150 metres short of the boundary of Sir James’ land.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

While it is not absolutely certain that the shed on the ‘floating church’ was built with corrugated iron sheets, most contemporary illustrations suggest that it was, which would make it Britain’s earliest tin tabernacle. Its floating days did not last long, though, as some time around September 1847 it broke free from its moorings during a storm and was blown ashore. There it stayed and was used as a place of worship until 1869.

As well as being quick to construct — overlapping corrugated iron sheets were attached to a timber frame above a brick foundation — tin tabernacles, as they were known, were relatively cheap to buy, costing anything from £150 for a chapel seating 150 to £500 for one accommodating a congregation of 350. By 1875, hundreds of corrugated iron churches were being erected around the country. In its 1879 catalogue, prefabricated building specialists, Francis Morton & Co Ltd of Liverpool, boasted that it had a dedicated church building department and had supplied nearly seventy churches, chapels, and school houses around the United Kingdom.

William Morris complained that they were ‘spreading like a pestilence over the country’, while the use of corrugated iron offended the sensibilities of John Ruskin, who condemned it in his seminal book, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1847). Tin tabernacles were still being built well into the 1920s and 30s.

Most corrugated iron churches were intended to be temporary solutions, buying time for the parishioners to raise the funds needed to meet the costs of a permanent structure. In 1896 residents, for example, in the Surrey village of Frimley Green erected a tin tabernacle on the site now occupied by St Andrew’s. When it rained, contemporary reports noted, the sound of the raindrops on the roof could drown out the sermon and in the summer it got uncomfortably hot.

By 1906 its congregation of around 250 had outgrown it and the following year a campaign was organised to raise money to build a larger and more permanent church. There were some bumps along the way, their spring fete having to be postponed because of the death of King Edward VII in May 1910, but by July 1911 funds, boosted by a loan from the Diocese of Winchester, were sufficient for work to begin. The new St Andrew’s church was completed, at a cost of £3,036, in time for the Easter celebrations in 1912, but the diocesan loan proved to be a mixed blessing, the church only being consecrated in 1928, once the loan had been paid off.

Doubtless to William Morris’ chagrin, there are still tin tabernacles that not only have survived but are being used as a place of worship. One such is the Church of St Paul in the village of Strines near Stockport, built to meet the spiritual needs of the workers at the nearby calico print-works at Strines Hall. Sixty feet long, 21.5 feet wide, and twenty-three feet to the ridge, and capable of seating 200, it opened for divine worship on August 29, 1880.

With exterior walls and roof made from corrugated iron, its wooden windows, according to the Stockport Advertiser (September 3, 1880), were embellished with stained glass depicting the Magi and other scriptural subjects. Disaster struck on Christmas Eve 1880 when the church caught fire, probably caused by decorations hung too close to the stove, causing damage estimated at around £250, but by April 23, 1881, it ‘had been thoroughly repaired and restored in every detail’, albeit at the expense of the stained glass windows. Over time the building has been extended with brick additions and passed from the ownership of the Nevill family in 1914 to the Diocese of Chester. It was designated as Grade II listed in 2011.

How many tin churches have actually survived to this day seems to be, curiously, a matter of some dispute. Historic England report that there are eighty-six remaining in England, of which fewer than twenty are listed. Some, like the Church of St Paul, are still used for worship, some now used for other purposes, such as Christ Church in Blackgang on the Isle of Wight, a holiday home, and others moved to museums like St Chad’s Mission Church which can now be found at Blists Hill Museum near Telford in Shropshire. Harriet Suter, though, in the comments section of the Historic England blog, claims, while researching for her Master’s dissertation on the conservation challenges of tin tabernacles (2020), to have found 157. Whatever the exact number is, the tin tabernacle is a fascinating example of new technology meeting a pressing spiritual need.

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Martin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in

Credit: Getty

Curious Questions: How do you tell the difference between a British bluebell and a Spanish bluebell?

Martin Fone delves into the beautiful bluebell, one of the great sights of Spring.

Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Curious Questions: Which came first — the plastic flower pot or the garden centre?

Martin Fone takes a look at the curiously intriguing tale of the evolution of nurseries in Britain.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson