Curious Questions: Do love potions actually work?

The idea of a potion that can make someone fall in love is as old as the idea of love itself. But is there anything in them that might actually have an effect? Ian Morton investigates.

In one of the best-known episodes of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, sleeping Titania’s eyelids are anointed with the juice of a magical plant and she awakes to fall in love with the first creature she sees: Bottom the weaver, his head transformed into that of an ass.

It’s a mystical moment for modern viewers but for Shakespeare’s audience, the notion of an effective love potion would not have been particularly strange. Philtres claiming to win the heart of another were central to medieval culture, as potions promising love were already as old as love itself.

History and literature record that they have never been out of fashion from the oft-retold Celtic legend of Tristan and Isolde and Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Sorcerer to Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and J. K. Rowling’s Hogwarts, potions have been plied to direct or misdirect romantic fortunes. In the current genre, young Harry Potter not only encounters potions, but also their antidote: Wiggentree twigs, castor oil and extract of Gurdyroot, a concoction absolutely in the magical mainstream tradition.

Love as a thunderbolt always had its own tradition, well expressed in ballads old and new. However, in the medieval period, doubts were quickly aroused if a gentleman of rank or wealth fell helplessly in love with an obviously unsuitable maiden.

It was easy to murmur witchcraft, an allegation difficult to dislodge, and often with fatal consequences to the 'witch' – some 200,000 of whom were burnt in early modern Europe. The suggestion of black magic having a role in love became so entrenched that it even gave rise to its own vernacular: to have been bewitched, spellbound, charmed, enchanted, enthralled, captivated or even fascinated by a female all derive from suggestions of the dark arts rather than a healthy and ingenuous attraction between man and woman.

Many love potions were complex, traditional, international... and utter nonsense. Human elements, including bone, hair, nail clippings and menstrual blood, featured widely. Animal remains often tossed in the mix included dove hearts, sparrow brains, stork droppings, snake fat, ass testicles, bat’s blood in beer, bones from the left side of a toad’s head eaten by ants and feline parts (cats were regarded as witches’ familiars and as such were cruelly treated).

Worms mixed with leeks and powdered periwinkle, best taken with meat, were supposedly good for fertile love-making. Consecrated bread stored under the tongue during Communion was a powerful ingredient when added to the potion to be drunk by the object of one’s desire.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

If you’re wondering how any concoction so vile might ever have been drunk, honey was often added to the more gruesome recipes for purposes of palatability, although it was also regarded as a positive component in its own right.

Love potions to invite affection and aphrodisiacs to provoke and prolong arousal were recorded in pre-Biblical Egypt, Greece and Rome. The Ancient Greeks favoured an orchid, Satyrion, which, when powdered and added to wine, rendered the drinker madly in love. They were so addicted that they utilised it to extinction, making it impossible to know if there was a genuine pharmaceutical effect at work.

Pliny the Elder recommended hippopotamus snout and hyena eyelid. Horace favoured dried marrow and liver. Rhino horn, crocodile dung and globe artichokes had their advocates. Mandrake root was regarded as a potent aphrodisiac, although the plant was said to scream when pulled up and elaborate precautions were needed to handle it, which added to its mystical intensity.

In Elizabethan England, prunes were considered sexually potent and were, therefore, served for free in brothels. The quest continued. Napoleon recommended truffles, Casanova suggested oysters and the Maharaja of Bikaner favoured ground-up diamonds.

But not everything was based on such whimsy, since many of the ingredients used do in fact produce real effects on the human body. Nightshade plants of the Solanaceae family that produce hallucinogenic alkaloids played a leading role in the pursuit of love and some potions and ointments could also be employed as poison.

Henbane was believed to induce true love and to bind couples together, and its narcotic effect is real – an overdose, however, can lead to delirium, coma and death. Verbena was also used, a sleeping draught which was thought to aid the seduction of a woman, but, when given to a man, could render him impotent for a week.

No male aphrodisiac was more dangerous than that derived from an emerald-green meloid beetle, Lytta vesicatoria, otherwise known as Spanish Fly. Its ability to inflate and sustain the libido had been known since ancient times thanks to its powerful constituent, cantharidin, which has a strong priapic effect on the male member.

The Spanish Fly’s downside has been known since ancient times: it can produce fatal kidney failure, and caused the painful demise of poet and philosopher Lucretius. It also ended the life of Ferdinand II of Aragon, the man who ushered in Spain’s Golden Age by sponsoring Columbus’s voyage of discovery and pushign the Moors out of the Spanish peninsula after 800 years of occupation. Ferdinan died in agony from an overdose at the age of 64.

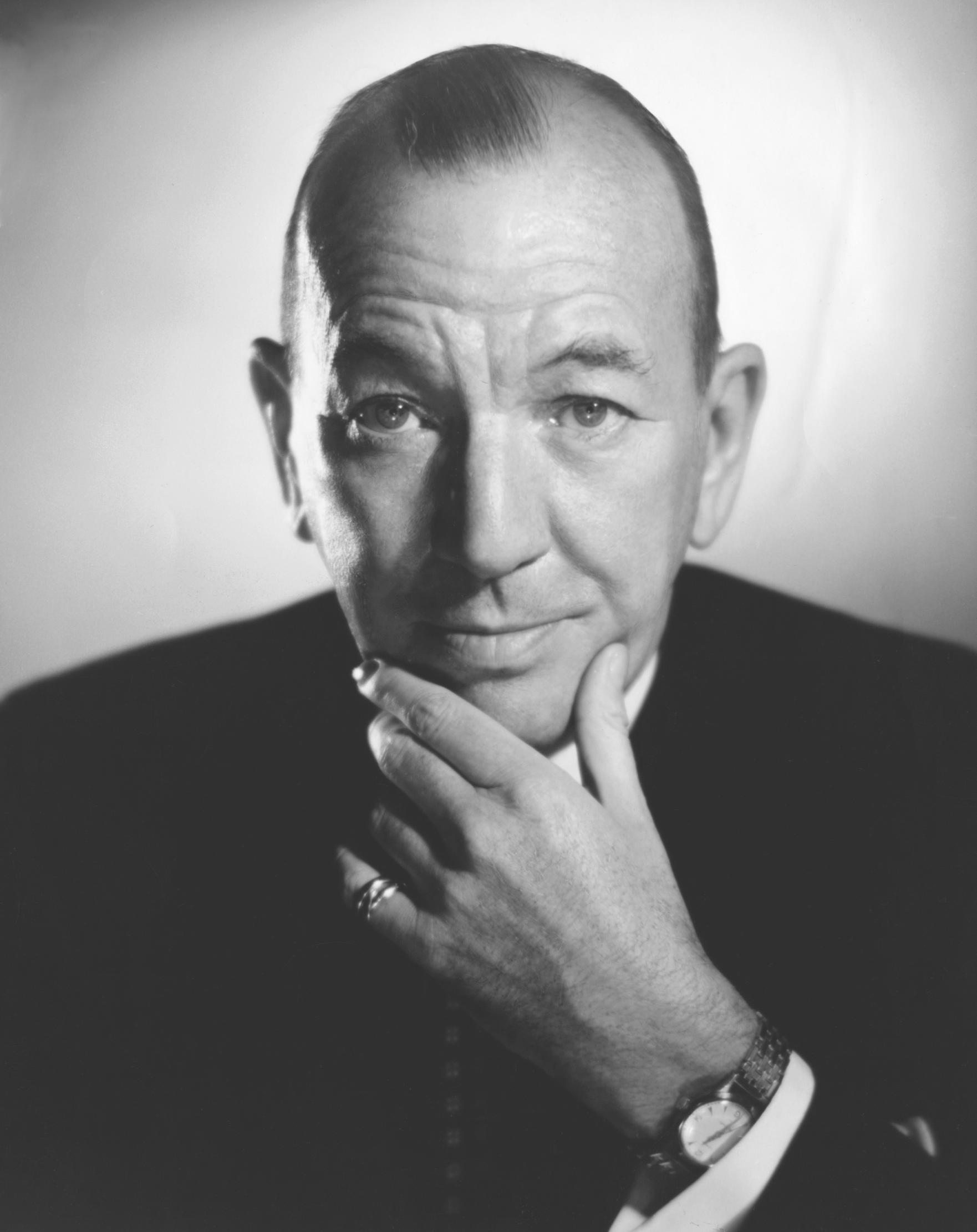

Despite recorded casualties, Spanish Fly survived as a sexual stimulant through the centuries, made scandalous newspaper headlines in the mid-20th century and remains available today as an alternative pharmaceutical preparation.

Curious Questions: How do you make the perfect cream scone?

Curious Questions: Why do the British drive on the left?

The rest of Europe drives on the right, so why do the British drive on the left? Martin Fone, author

Credit: Rex

Curious Questions: Why do we still use the QWERTY keyboard?

The strange layout of keyboards in the Anglophone world is as bafflingly illogical. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Curious Questions: Why do actors say ‘break a leg’?

The best-known phrase for wishing an actor luck is also the most baffling. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comeback

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comebackThe Kentish glory moth has been absent from England and Wales for around 50 years.

By Jack Watkins

-

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?It was the home of Mr Gruber and his antiques in the film, but in the real world, Alice's Antiques could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.

By Martin Fone