Curious Questions: How will we greet each other in a post Covid-19 world?

Kissing cheeks will surely be frowned upon, and even the humble handshake may struggle to regain its pre-eminence. But what other options will we have for greeting each other when the world gets (cautiously) back to normal?

When we waved goodbye to 2019 BC (Before Coronavirus), did we say farewell to a way of life that we took too much for granted? Practising social isolation has provided me with ample time to reflect upon what is important in my life and, on those occasional forays outdoors, social distancing has challenged me to consider how I do and should interact with my fellow human beings. The exercise has been salutary.

Searching for the positives we can thank the Covid-19 pandemic for, I console myself that the end of cheek kissing as a form of greeting must be nigh. Giving a peck on each cheek, whilst making a stifled ‘mwah’, has become almost de rigueur in increasingly widening circles here in England. Although it is a common practice in France and other European countries — the socialist cheek kiss was routinely practised when Communist bloc leaders met — I have always found it mildly disconcerting when someone I barely knew presented a cheek in anticipation of me pecking it or, worse still, launched themselves rapidly in the direction of my face. I am sure that we will all think twice about doing that again.

The same could be said about my preferred form of greeting, the handshake. Most of our tactile engagements with the environment are through our hands and it is a natural reflex, when someone comes into our social space, to grasp them. Social convention is to clasp their right hand with yours and gently squeeze.

The squeeze is all important and the recipient can tell a lot about your personality and intentions from the way you grasp their hand. A limp and floppy handshake can reveal a lack of commitment, indifference and even weakness. On the other hand, those who seem determined to restrict temporarily the flow of blood to your extremities and to crush your bones have a misguided sense that they are displaying dominance, superiority and a no-nonsense approach.

Getting that squeeze just right is a tricky business and 19th century books on etiquette were full of helpful advice on how to shake hands. The consensus seemed to be that it had to be firm, not like a dead fish, but not overly strong, unlike the bone crusher. Some even warned that an injudicious choice of handshake could lead to social ostracism, one from 1877 advising that ‘a gentleman who rudely presses the hand offered him in salutation, or too violently shakes it, ought never to have the opportunity to repeat their offence’. Sound advice, I would say.

‘The fist bump, out of the context of the sporting arena and practised by anyone other than millennials, looks ludicrous’

Handshaking has a long history. The earliest pictorial representation of the gesture appears in a relief from the ninth century BC (Before Christ), found during excavations of the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud, about thirty kilometres south of modern-day Mosul. The Assyrian king, Shalmaneser III, is depicted as sealing an alliance with a Babylonian king by shaking hands, a gesture indicating trust and equality of status. In the Homeric Iliad, the clasping of the right hand was seen as the affirmation of an oath, Agamemnon, in Book 4, reminding his brother, Menelaus, of their oaths to take revenge on Troy that were in the form of ‘drink offerings of unmixed wine and handclasps in which we put our trust’.

The ancient Greeks practised a form of handshake known as dexiosis, roughly translated as ‘taking the right hand’. Stelae, a type of stone tablet bearing inscriptions and carvings, showed mortals and gods communing through a handshake. On gravestones the deceased would sometimes be depicted shaking hands with a family member, symbolising, depending upon which expert you believe, either a final farewell or the eternal bond that links the living with the dead. To the Romans the handshake represented friendship and loyalty and a pair of clasped hands were used on Roman coins in the first century AD.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In mediaeval times fede rings, featuring a pair of clasped hands, were a tangible symbol of the pledging of vows and were particularly associated with marriage and deep friendship. From the 17th century physical handshakes came back into vogue, seen as a more egalitarian form of greeting than bowing and scraping to your betters, especially among the Quaker community. As a form of greeting it is now deeply ingrained into the way we interact with our friends and acquaintances, old and new. However, in these mysophobic times a gesture, symbolising friendship and good wishes, can also be viewed as a pretty effective way of transmitting germs. It just will not wash.

‘The doffing of a cap or hat not only has connotations of a master servant relationship but also requires you to wear one in the first place’

What will replace it is open to speculation. I may be a tad old-fashioned, but to me the fist bump, out of the context of the sporting arena and practised by anyone other than millennials, looks ludicrous. The elbow bump, initially popularised in the Kaluapapa Leprosy Settlement in Hawaii in the late 1960s and finding a new lease of life during the 2014 Ebola epidemic to such an extent that it was dubbed the ‘Ebola elbow’, has also seen a revival. As a manoeuvre, though, it is hardly the epitome of social grace. The doffing of a cap or hat not only has connotations of a master servant relationship but also requires you to wear one in the first place.

Casting my net wider, there is ojigi and specifically ritsurei, the ritual of bowing as practised in Japan. Used as a sign of salutation, as well as reverence, apology or gratitude, you must keep your back perfectly straight whilst bending your body at the waist to pull it off properly. If that seems a little over the top, there is always the more Teutonic nod of the head. The accompanying click of the heels is probably unnecessary.

In the Indian subcontinent and other parts of Southeast Asia, people are greeted and taken leave of with the Añjali Mudrā, a slight bow, hands pressed together with palms touching and fingers pointing upwards and thumbs close to the chest. The gesture may be accompanied with the word ‘Namaste’, meaning welcome. In Thai culture, a similar gesture is known as the wai. It has always struck me as particularly elegant and tops my list of greetings to adopt when social intercourse resumes.

One form of greeting that I will not be using is the traditional Tibetan practice of sticking your tongue out. It owes its origin to the 9th century when a cruel king terrorised the country. His tongue was black and by revealing your tongue, you can prove that you are not like him nor his reincarnation. If you are ever in Tibet, just remember to steer clear of liquorice.

Curious Questions: Why do Australians call the British 'Poms'?

With England about to take on Australia in The Ashes, Martin Fone ponders the derivation of the Aussies nickname for

Credit: Alamy

Curious questions: Are you really never more than six feet away from a rat?

It's an oft-repeated truisim about rats, but is there any truth in it? Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Curious Questions: How likely are you to be killed by a falling coconut?

Our resident curious questioner Martin Fone poses (and answers) another head scratcher - or should we say, head banger?

Credit: Photo by FLPA/Hugh Lansdown/REX/Shutterstock – Bullet Ant (Paraponera clavata) adult, standing on leaf in rainforest, Tortuguero N.P., Limon Province, Costa Rica

Curious Questions: What is the world’s most painful insect sting – and where would it hurt the most?

Can you calibrate the intensity of different insect stings? Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions', investigates.

Credit: Morgan Hancock / Getty

Curious Questions: Why do cricketers call it a 'duck' when they get bowled out for 0?

Martin Fone, author of 50 Curious Questions, explains how a duck egg led to the popularisation of a term in

Curious Questions: What is the perfect hangover cure?

If there's a definite answer, it's time we knew. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions', investigates.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwards

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwardsCampaigners in England often point to Scotland as an example of how brilliantly Right to Roam works, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, says Patrick Galbraith.

By Patrick Galbraith

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone

-

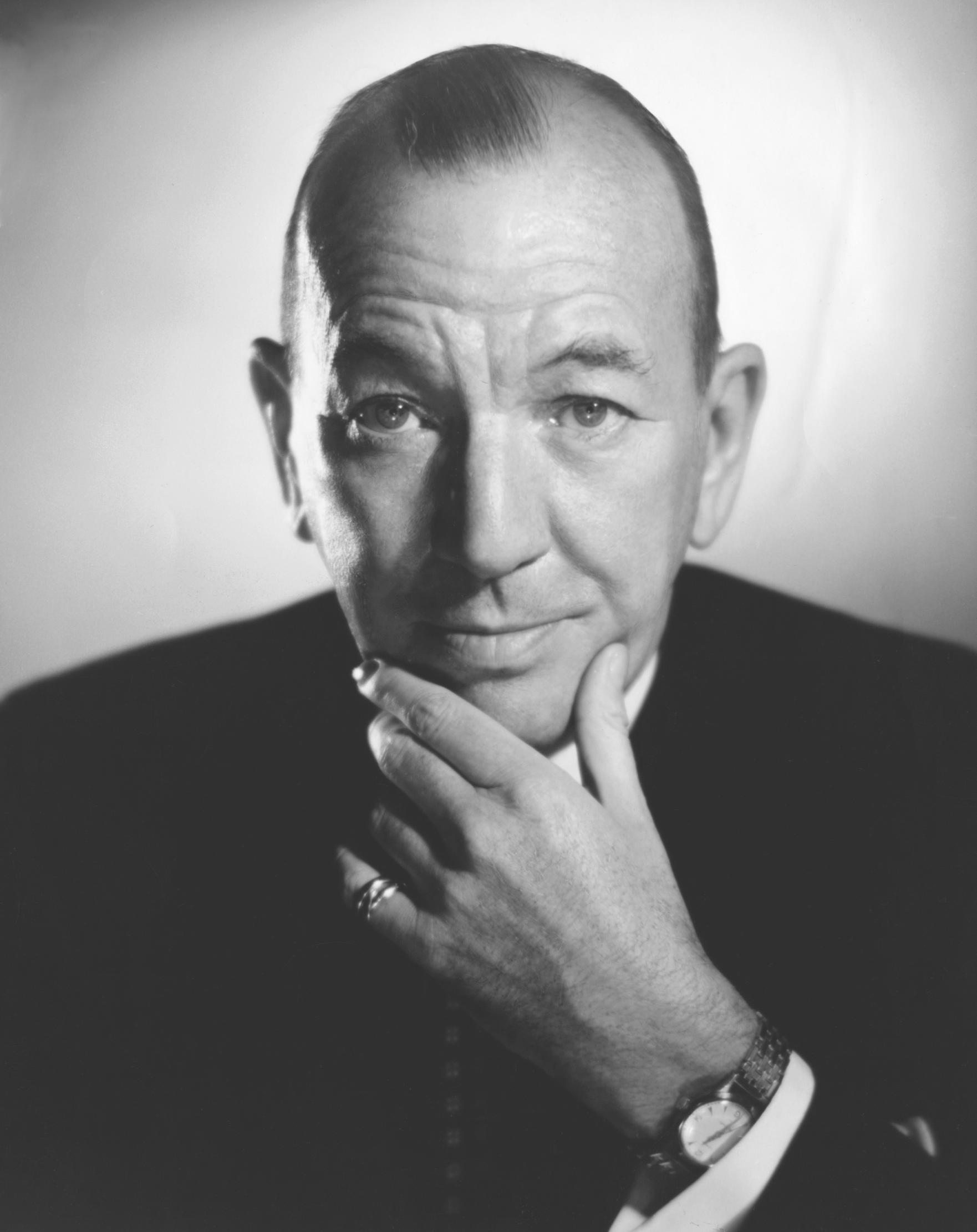

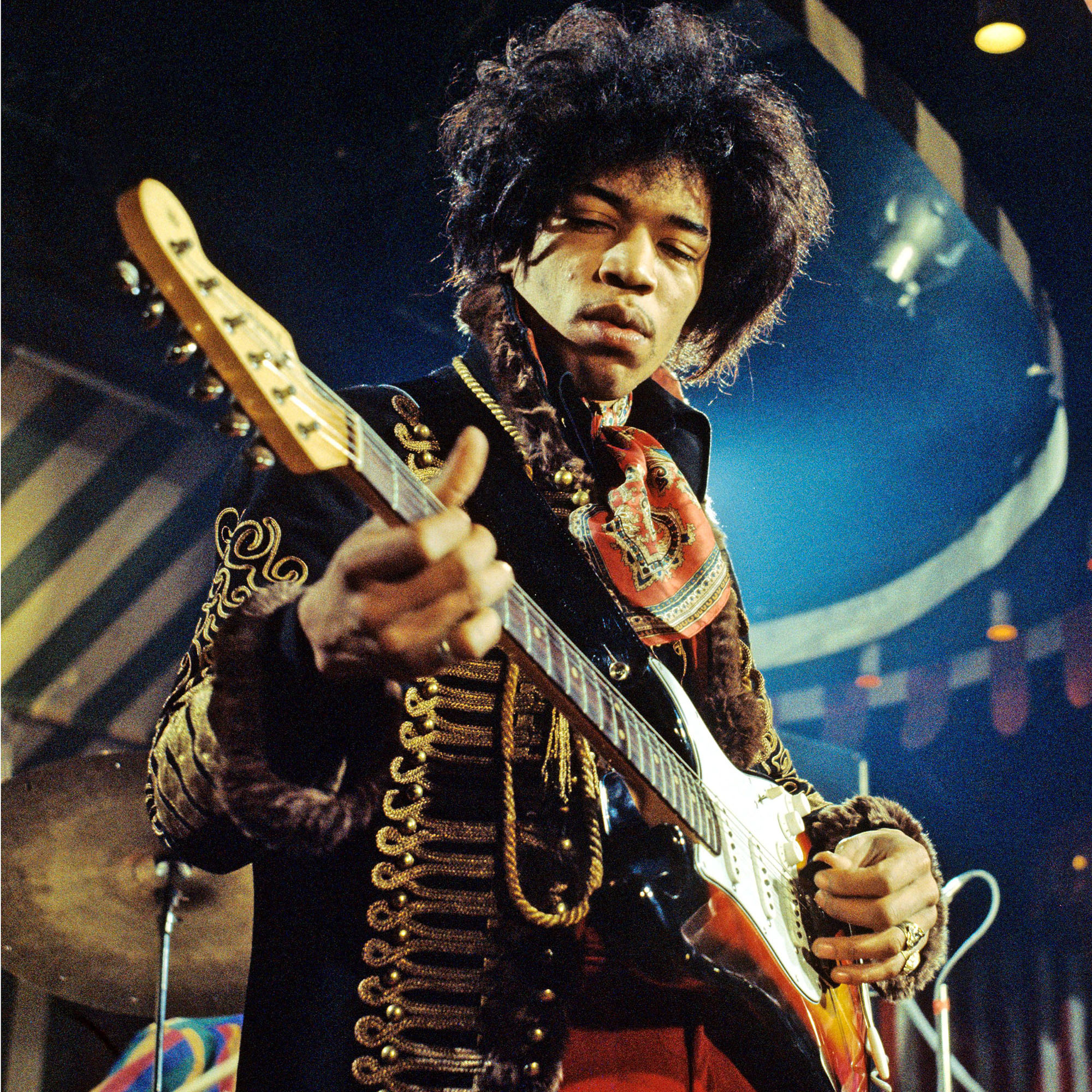

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.

By Martin Fone