Curious Questions: How do you survive social isolation? A former Royal Navy submarine commander on the five things you need to do

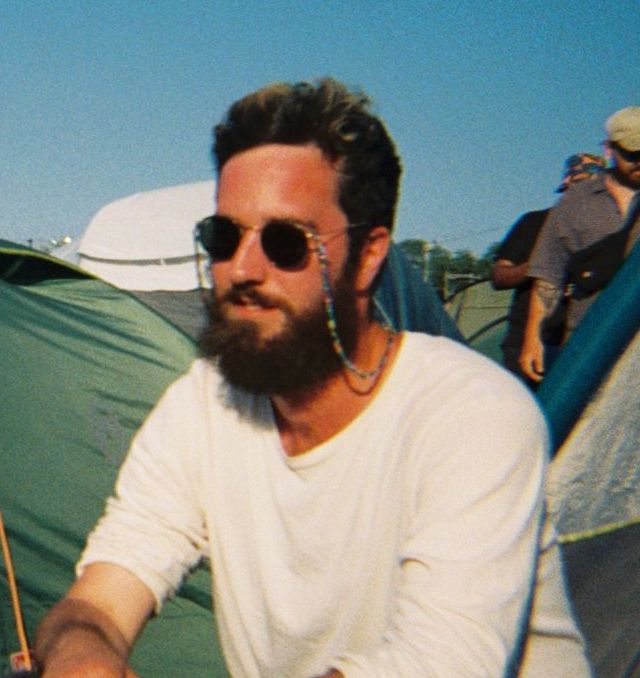

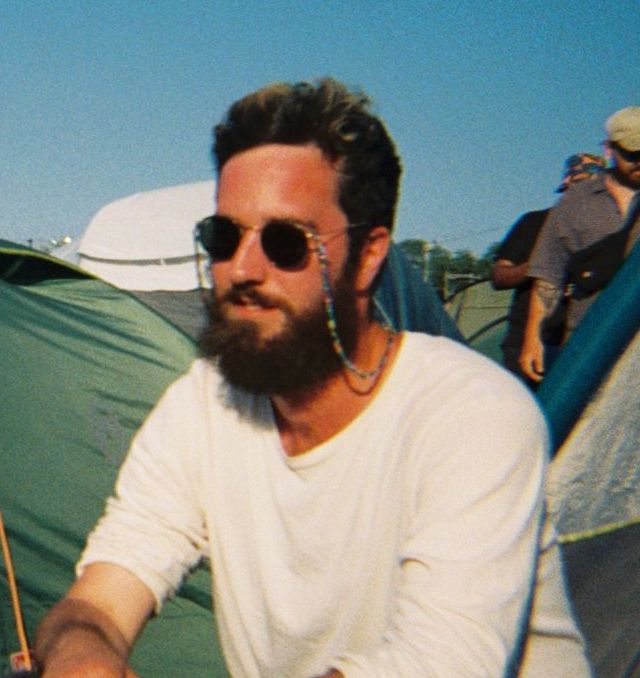

The vast majority of us are in uncharted waters when it comes to dealing wth life in lockdown. But there are some who know all about isolation from the rest of the world — and submarine crew are at the top of the list. James Fisher spoke to Commander Ryan Ramsey, a former submarine skipper in the Royal Navy, to get his tips.

Sitting inside for most of the day is not a lifestyle most of us are particularly used to, or for that matter, a lifestyle that most of us enjoy. It’s certainly not something I would choose to do.

Commander Ryan Ramsey, however, is looking at the positives.

‘I appreciate the freedom I have at the moment. The freedom to go for a run, to hear the birds sing, to look out the window at the garden,’ he tells me. ‘Those freedoms are denied to you on a submarine.’

Cmdr Ramsey spent 26 years in the Royal Navy, three of which as captain of HMS Turbulent, and a further two years as ‘Teacher’ of the notorious Perisher course, where new captains are put through gruelling physical and mental duress to see if they have what it takes to command the UK’s most powerful defence assets. On one patrol in 2011, Cmdr Ramsey and his men were at sea for 286 straight days, 237 of which were submerged, which puts my mild anxiety at being locked up in my Battersea flat for just 20 in some perspective. On top of all of that, he went willingly.

‘I didn’t join the navy as a submariner, but every person who signs up gets a day at sea on a sub. That was when I changed my mind,' he tells me.

'I was overawed by the teamwork and everything else that went with it. A submariner was what I wanted to be, it was what I wanted to do, and from then on I didn’t look back.’

Pressure is the name of the game in the Silent Service, both physically and mentally. When I ask about his most his challenging day at sea, Cmdr Ramsey tells me about a situation in the Indian Ocean, where the cooling system failed and temperatures on board became dangerously high. ‘People started dropping down due to heat exhaustion. You couldn’t ask for help, you couldn’t go anywhere, so we just had to fight through it,' he says.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'I took an unprecedented decision, which was to dive the submarine very deep to keep it cool while we fixed the problem, which we managed to do,’ he adds. ‘It was my best and worst day in command. What it proved to me is that teamwork wins, and that empowerment is everything.’

Discussing the daily life on board a submarine, it becomes clear that few people are better equipped to deal with the current enforced lockdown. ‘It’s an interesting mix of about 70 percent boredom and 30 percent adrenaline,’ he reminisces.

‘Most of the crew are six hours on, and six hours off, on two watches. You wake up, in a small compartment, with 27 other men, have some breakfast, do a briefing, and then get to your station for six hours. You then get off watch, maybe have some lunch, a bit of exercise, de-stress with some games or tv, and then sleep. Without routine, life on board becomes unsustainable.’

‘Submariners are a different breed. Everyone, from top to bottom, goes through the same training to get their Dolphins [the submariners’ badge]. You’re sharing that steel tube and you’re on your own. There’s nowhere else to go.

'You live and die together. And finally, you get to know the strengths and weaknesses of everyone you live with. You go through life- changing events that last forever.’

So what advice for us landlubbers then? I barely finish the question before Cmdr Ramsey answers — ‘routine’.

‘Humans don’t like to change, and in the current situation we’ve been forced to change without the relevant training or time to adapt. Developing a routine within your home, however big or small, is very important. And don’t forget to change it up at the weekend.'

'The second thing is cleanliness: keep your house and yourself clean, as it’s important to be disciplined.

'Thirdly, it’s important to take a break! All your travel time to and from work is gone, and people get up and go straight to their laptops. You need proper breaks, from work, from the news and from everything else.

‘Finally, when living in a group, is communication and de-confliction. Spot when tensions are rising, between housemates, family members, loved ones or whoever, and have conversations early to avoid those peak arguments,’ he advises.

Unlike many of my friends, Cmdr Ramsey is effortlessly calm throughout our entire conversation, constantly steering away from the negatives of lockdown and looking at the positives. He speaks about how, during times of stress on board HMS Turbulent, his favourite memories were of playing Uckers, a naval boardgame, and the camaraderie and laughs that would come with it. He told me about how life under the waves made him appreciate watching the sun rise and the sun set, and how he would listen to the dolphins chasing the submarine when dived. ‘I just enjoyed being surrounded by great people all the time.’

His final piece of advice is particularly uplifting. ‘We have loads of communication paths, so use them,’ he says.

‘It might not feel like it, but we’re more connected than ever, so talk to people, and don’t just talk about work. Reach out to as many people as you can and you’ll even meet new friends, albeit virtually.’

When it comes to lockdown, we’re all in the same boat. Just be thankful that it has windows and sofa.

Credit: Getty Images

Curious Questions: Why do the clocks go forward in Spring?

As we move from Greenwich Mean Time to British Summer Time, Martin Fone ponders the reasons why — and wonders if

Curious Questions: What caused Tulipmania?

Curious Questions: Should animals wear clothes?

Martin Fone, decidedly not an animal person, ponders whether animals should wear clothes and, indeed, what a stylish pet would

Credit: Getty

Curious Questions: Can horses really heal humans?

The claims made for how horses help humans get over all manner of trauma stretch back to ancient times. Pippa

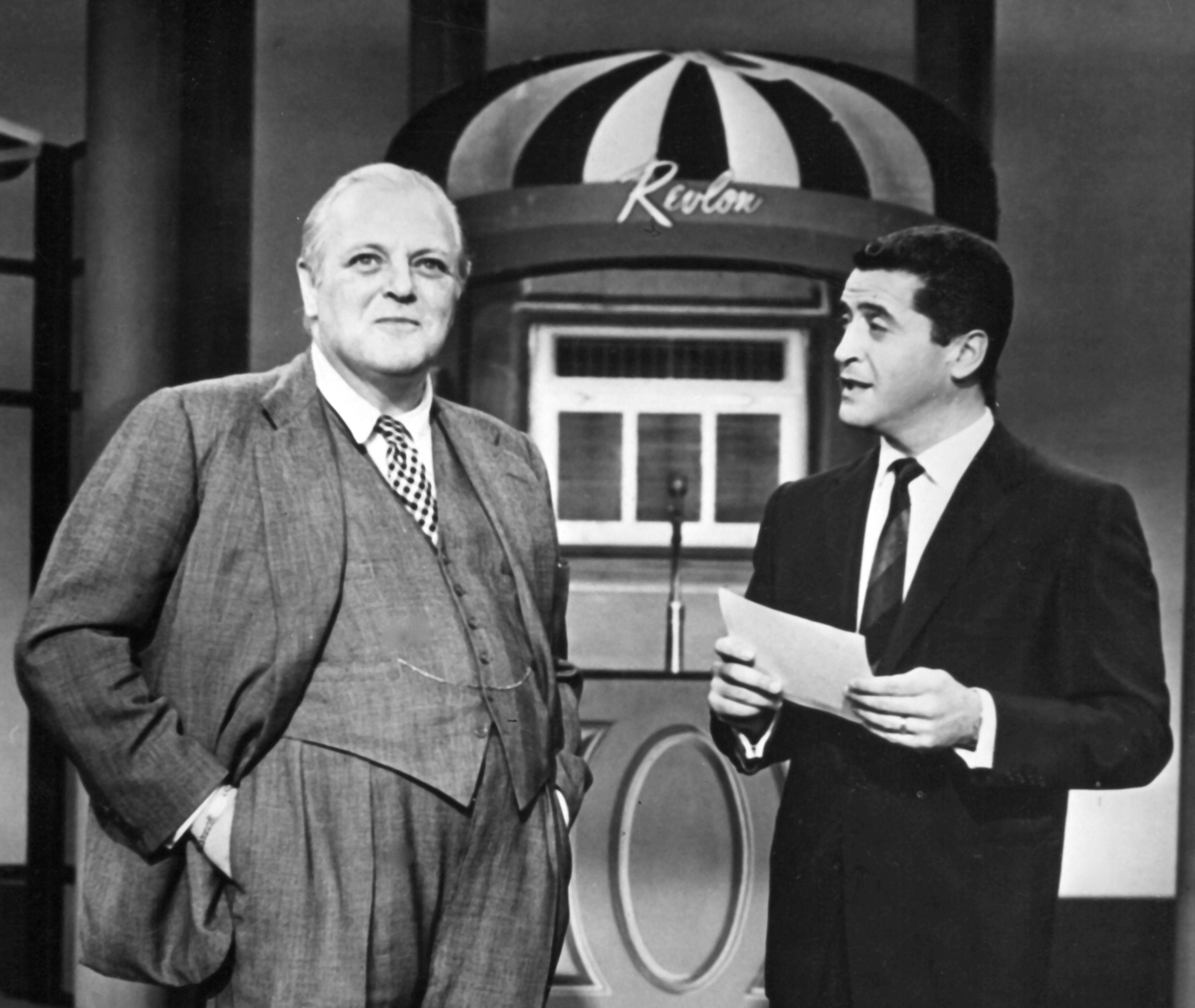

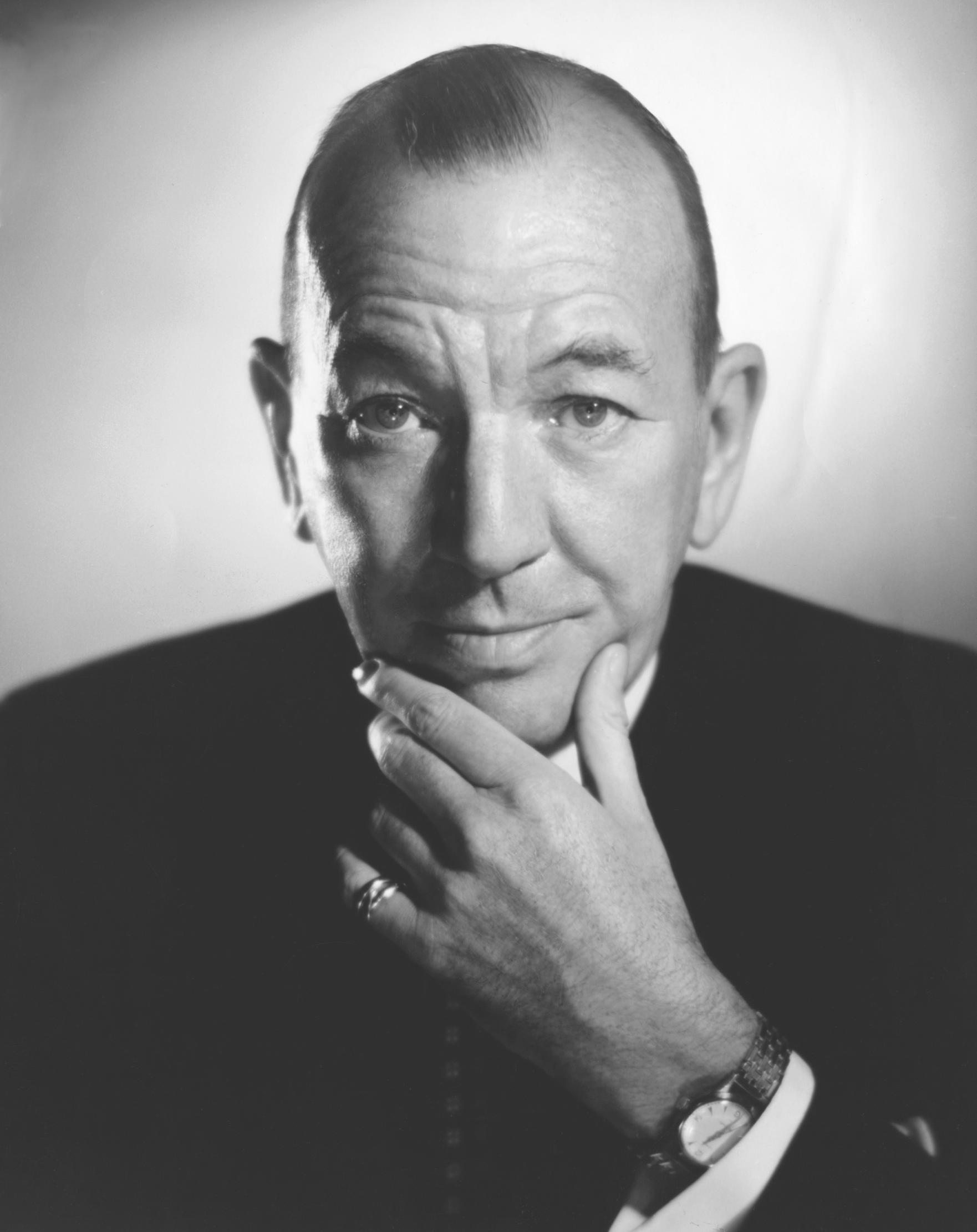

Curious Questions: Why do we talk about the '$64,000 question' — even in a country where we don't use dollars?

A question about a question? Absolutely. Martin Fone gets to the bottom of where this curious phrase originates — and how

James Fisher is the Deputy Digital Editor of Country Life. He writes about property, travel, motoring and things that upset him. He lives in London.

-

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day blows smoke, tells the time and more.

By Toby Keel

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.

By Martin Fone