Curious questions: Who administered the first vaccination?

If you thought it was Edward Jenner, think again: Martin Fone discovers that the practice of inoculating against the smallpox disease has much older origins than you'd have believed possible.

It was not the Valentine’s Day treat we really had in mind, but my wife and I were more than happy to visit the local vaccination centre — appropriately sited at the former venue of the BDO World Darts Championship — to receive the first of our two Covid-19 injections. The sense of hope it brought gave me a metaphorical shot in the arm.

When I listen to the debates and publicity around the vaccine, I shudder every time I hear the word 'jab'. Why is there a need to dumb down our language? Trying to rationalise this lamentable trend, I wonder whether, in these days of religious and dietary sensibilities, vaccination, with its roots in vacca, Latin for cow, is too much of a red rag to a bull.

What is wrong with 'injection'? After all, in the context of injections, jab has a rather tawdry past, first used in the early 1900s as slang for an injection by morphine and cocaine addicts.

For centuries, smallpox was a highly contagious disease, caused by the variola virus. The early symptoms were a fever, tiredness, and headaches, followed by the appearance of a distinctive red rash, initially on the face and upper arms and then spreading all over the victim’s body.

The mortality rate was as high as 30%. Of the survivors between 65% and 80% bore prominent, deep pitted scars, known as pockmarks, for the rest of their lives and many were blinded.

Milkmaids in the Gloucestershire area were famed for their clear complexions and the distinctive pustules on their hands and arms from exposure to the viral skin infection known as cowpox. Unsightly as they were, they seemed to give the women some immunity from the worst of smallpox.

Intrigued, a local physician, Edward Jenner, took the bold step in 1796 of taking some matter from a cowpox pustule that had formed on the hand of a milkmaid, Sarah Nelmes, and injected it into the arm of James Phipps, an eight-year-old boy.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Whilst experiencing a mild fever and some soreness which lasted a day, Phipps proved immune to the disease, when Jenner injected some smallpox matter into his arm six weeks later and on subsequent occasions.

In 1798, Jenner published his results in An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of Variolae Vaccinae, establishing that a shot of a preparation made from cowpox not only protected against smallpox, but also allowed immunity to be passed from one person to another.

Having successfully developed a vaccine, he devoted the rest of his life to promoting his work and immunising the local Gloucestershire folk, converting the thatched summerhouse in his garden in Berkeley into possibly the world’s first free vaccination centre, grandiloquently named The Temple of Vaccinia.

The idea of exposing yourself to a mild form of disease to gain an immunity to it — variolation, as it was known in the context of smallpox — had been around centuries before Jenner’s breakthrough.

The redoubtable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British ambassador to Constantinople, saw the practice in operation there in 1717 and became an ardent fan.

'Every year,' she wrote, 'thousands undergo this operation… and they take smallpox here by way of diversion as they do waters in other countries.' Lady Montagu had her children inoculated, her son in Constantinople and her daughter on her return to London in April 1721.

She was instrumental in arranging, by way of an experiment, for several prisoners and abandoned children to have smallpox scabs inserted under their skin. Some months later, they were all exposed to smallpox, but none fell ill.

Impressed, Caroline, Princess of Wales, gave the procedure the royal imprimatur by having her children inoculated. Variolation was not without its risks; some patients, including one of George III’s sons, died during the procedure and the disease, even in its mild form, could spread to others who had not been protected.

The intense interest in variolation engendered by these women prompted James Jurin, Secretary to the Royal Society, in 1723 to investigate further. Among the evidence he collated was a letter from a Welsh doctor, Richard Wright, who reported that variolation had been practised for many years in the Haverford West area.

Wright told of a 90-year-old man who had been variolated as a child, as had his mother before him. If so, this form of inoculation against smallpox would have been practised as early as the beginning of the 17th century.

The desire to give your child some protection against smallpox led to a morbid trade known as 'buying the pocks'. In Scotland, smallpox-contaminated wool was bought and wrapped around a child’s hand. Elsewhere, parents would buy smallpox-infected clothes for their children to wear.

Other popular techniques included holding smallpox scabs in your hand or rubbing them onto the skin or into a circular, open wound. It proved a sound investment as those who had been inoculated in this way recorded much lower mortality rates than their peers.

In the United States, exposure to the smallpox virus enhanced a slave’s worth. A slave whose given name was Onesimus told his owner, Cotton Mather, that in his homeland, in what is now southern Libya, he had 'undergone an operation which had given him something of the smallpox and would forever preserve him from it… he showed me in his arm the scar which had been left upon him'.

Pus from an infected person had been rubbed into a cut or needle prick in his arm, an almost identical form of inoculation to that practised in West Wales and the Ottoman empire.

According to Charles de La Condamine, writing in 1773, variolation had been practised in West Africa since 'time immemorial'.

When a smallpox epidemic struck Boston in 1721, Mather sought to interest the city fathers in the immunisation techniques he had learned from Onesimus. Instead of earning their gratitude, he was nearly run out of town for daring to take the word of a slave.

One physician, Zabdiel Boylston, did listen, though. After inoculating members of his own household, in what were the first known inoculations in America, and discovering they had developed immunity, he persuaded 280 of the city’s 11,000 residents to follow suit.

Mortality rates fell by five-sixths among those who had been inoculated. Onesimus’ contribution to the immunisation story was only recognised in 2016, when Boston Magazine included him in its top 100 Bostonians of all time.

In China, Emperor K’hang Hsi, a smallpox survivor himself, boasted in the late 17th century that he had inoculated his whole family against the virus. The preferred Chinese method, contemporary manuals showed, was to blow a powder made from ground, dry smallpox scabs up the child’s nose. Alternatively, fluid was collected from a pustule onto a cotton plug and placed up the nostril.

Written evidence suggests that these methods were practised in China and India from at least the 16th century and probably much earlier, some scholars suggesting that variolation had been practised for two millennia.

Jenner may have administered the first vaccine in 1796 but jabbing has a much longer legacy still.

Curious Questions: Who invented tennis?

It's 150 years since the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club was formed – though originally it was solely for

Curious Questions: What caused Tulipmania?

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin Published

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson Published

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone Published

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes Published

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins Published

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone Published

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone Published

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone Published

-

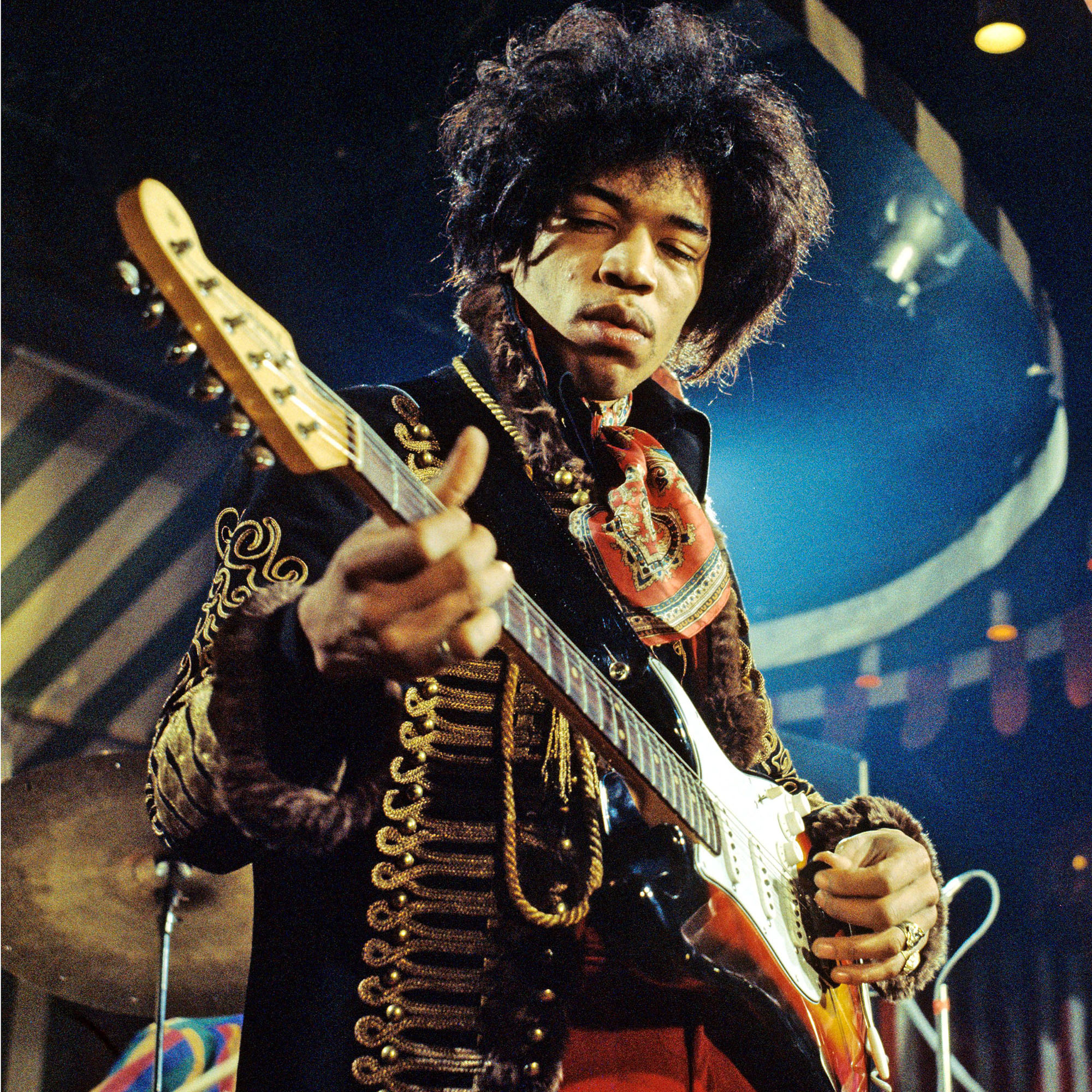

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel Published

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.

By Martin Fone Published