Curious Questions: Did an Englishman called John Stringfellow really invent powered flight half a century before the Wright Brothers?

A throwaway comment in a piece by Jason Goodwin made us question something we thought we always knew: that the Wright Brothers invented powered flight. So we asked Martin Fone to investigate the life of John Stringfellow and find out if he really did beat the famed American pioneers to the punch.

Felix Mendelsohn perfectly encapsulated man’s ambition to emulate birds in the final verse of his anthem, Hear My Prayer; 'O’ for the wings of a dove, for the wings of a dove, far away, far away I would rove'. There is something liberating about the idea of soaring into the air.

The Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus tells how they strapped on wings coated in wax and flew off into the sunset to escape the cruel Cretan king, Minos. Icarus, though, ignored his father’s instructions and flew too near to the sun. The wax melted, he crashed to the ground and died.

A stark reminder of the perils of hubris for sure, but for me the myth shows that man’s desire to fly has been deeply engrained in his psyche for millennia, a wish only truly satisfied in the 20th century.

Indeed, records show that several attempts to fly were made well before Leonardo da Vinci plied his mind to the subject. In Córdoba, the ninth century polymath, Abbas ibn Firnas, covered his body with feathers, attached a couple of wings, climbed up high and launched himself into the air. He flew a considerable distance but 'in alighting again at the place whence he started, his back was very much hurt'.

Closer to home, William of Malmesbury reported in Gesta Regum Anglorum (1125) that a fellow monk, Eilmer, fixed wings to his hands and feet, climbed up on to the tower of Malmesbury Abbey and flew for more than a furlong. Landing proved his undoing: 'Agitated by the violence of the wind and the swirling of the air, as well as by awareness of his rash attempt, he fell, broke both his legs and was lame ever after.'

Abu Nasr Al-Jawari is famous for compiling the al-Sihah, the go-to Arabic lexicon of the Middle Ages, notable for being the first to put its entries into alphabetical order. He also earned a small footnote in the chronicles of aeronautical history.

To add some spice to his otherwise dull life amongst the archives, at the turn of the 11th century he climbed on to the roof of a nearby mosque wearing a pair of wings. Throwing himself off, he plummeted to the ground and killed himself. A student had to finish off his dictionary.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Montgolfier brothers were the first to harness third-party power to achieve lift-off, building a balloon made of silk and lined with paper, some 33 feet in diameter, and propelled by hot air. On June 4, 1783 it rose, unmanned, from the marketplace in Annonay, reaching a dizzying height of almost 6,600 feet. Its journey of over a mile was accomplished in around ten minutes. For aeronautical enthusiasts like John Stringfellow their success opened up a world of possibilities.

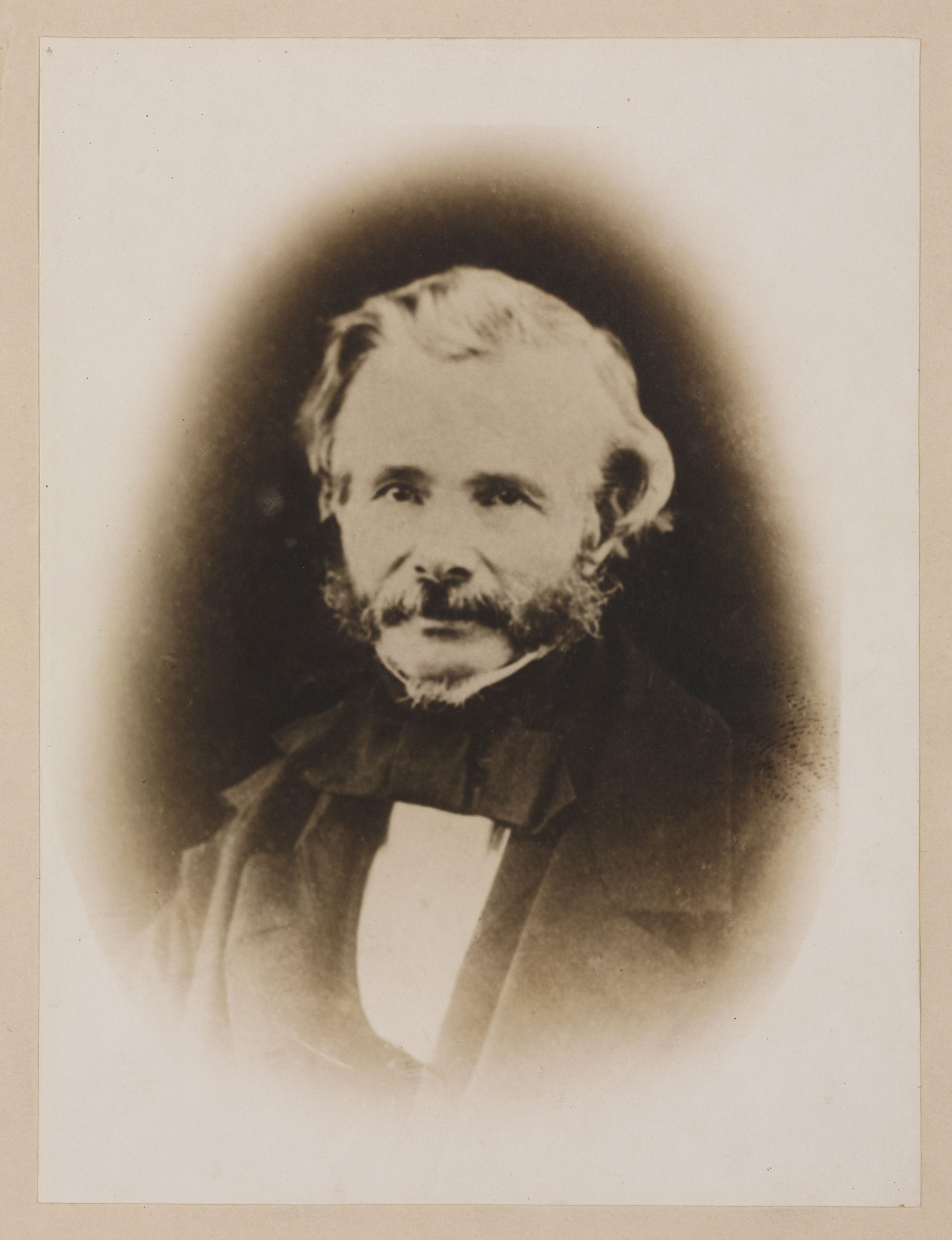

An engineer making bobbins for lace-making machines in the Somerset town of Chard by day, Sheffield-born Stringfellow spent his spare time working on propellor-driven balloons, one of which landed on nearby Windwhistle Hill in 1831, now curiously a hotbed for supernatural sightings.

Later that decade he met up with William Henson, who ran Oram’s Lace Mill, and the pair pursued their dream of building a self-propelled flying machine capable of carrying people and goods. By 1840 they were busily observing bird flight and studying stuffed rooks to establish the optimal ratio of wing size to weight to achieve lift-off.

Abandoning the idea of moveable wings, they fixed on static wings set an angle and a steam engine as the source of power for their machine. To the undoubted astonishment of his fellow passengers, Stringfellow occupied his time on a train journey to London by throwing out of the window models with different wing shapes and sizes to test which would be most suitable.

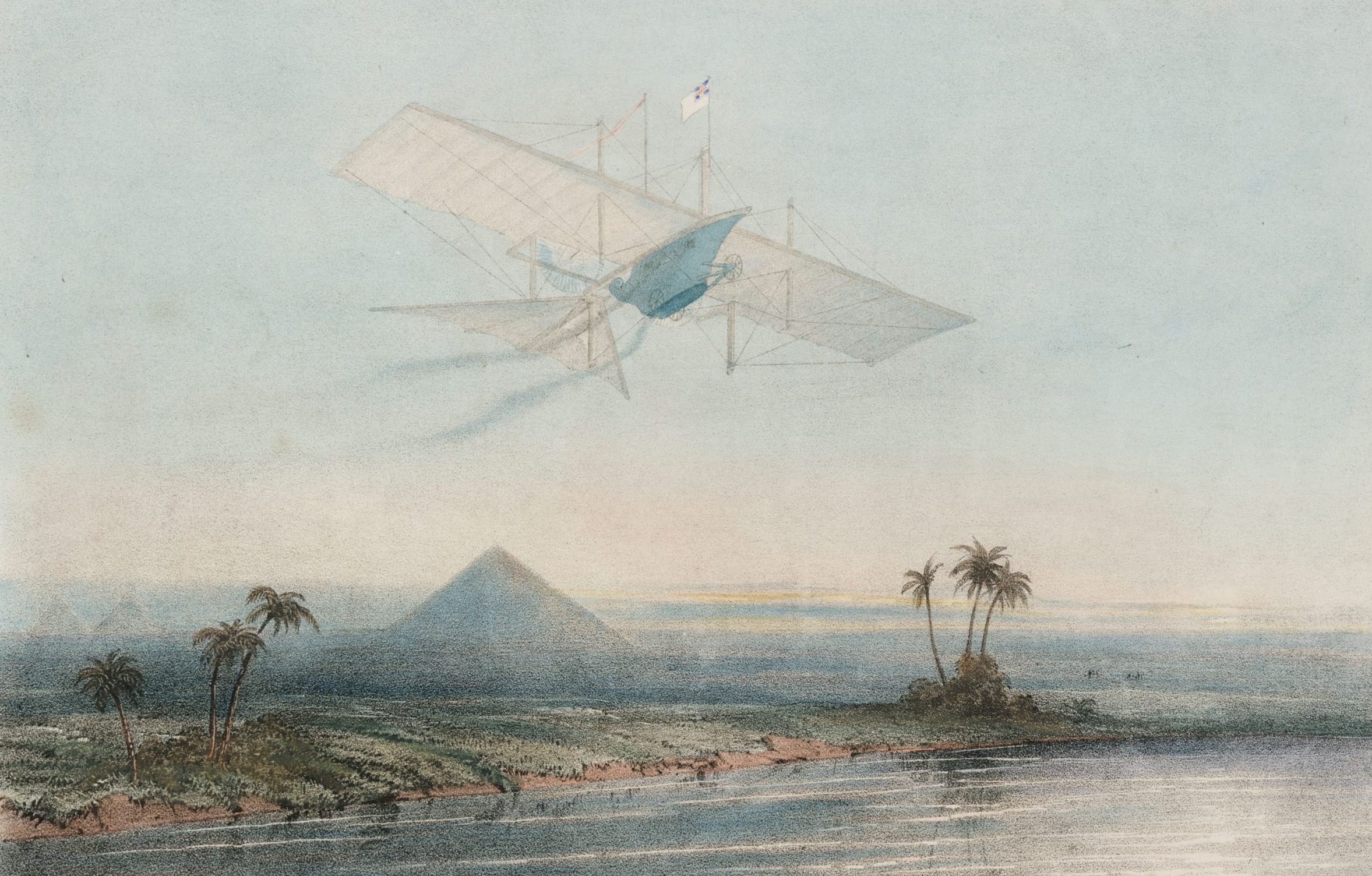

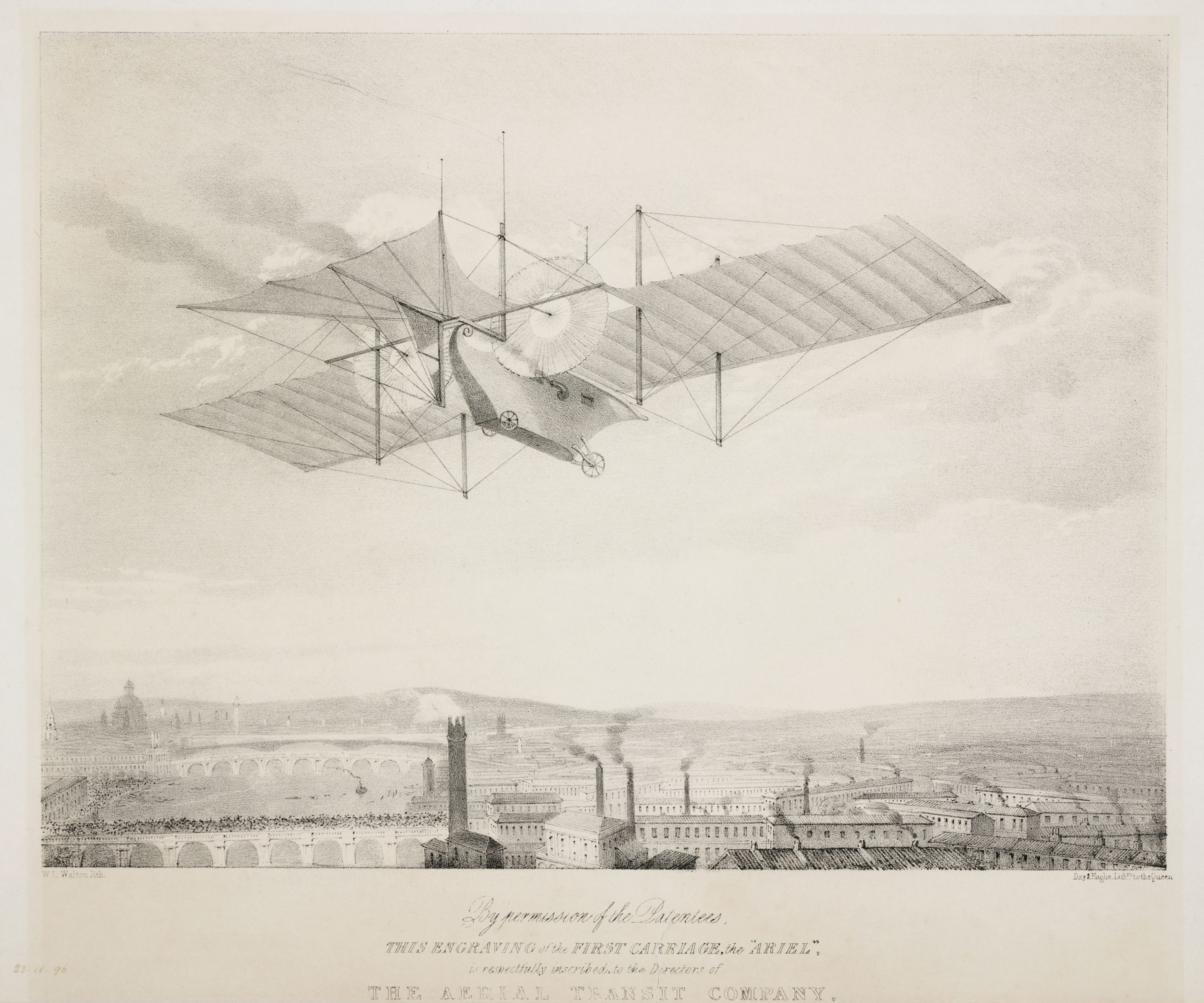

They patented the 'Aerial Steam Carriage' in 1842 and the following year established the 'Aerial Transit Company', potentially the world’s first airline. Discernible progress was slow, though, and by 1845 Henson had lost interest, got married and migrated to America where he patented a safety razor.

Stringfellow was made of sterner stuff — and had to be.

His attempts to achieve lift-off exposed him to the ridicule and scorn of the worthy denizens of Chard, so much so that he conducted his experiments under the cover of night to evade the attentions of the scoffers. Judging that his machine, now boasting a twenty-foot wingspan, was ready to fly, he had it carried down to Bala Down, half a mile west of Chard.

Alas, the early morning dew had made the fabric on the wings heavier than anticipated and the engine had insufficient thrust to take off. Every day for seven weeks Stringfellow tried to get the machine to fly but each time it stubbornly refused to. He had to admit defeat.

Undaunted, John made significant alterations to the design. Steam was the only viable form of propulsion at the time, but by developing a paper-thin copper boiler weighing just twelve ounces he was able to produce a lightweight engine.

For the plane itself he deployed a lightweight wooden frame and bat-like wings covered in silk, halved the span to ten feet and used two huge contra-rotating propellors to provide lateral stability. It weighed around nine pounds.

Lacking a vertical fin, it would lurch sideways if it encountered even the slightest bit of turbulence. Sensibly, Stringfellow conducted his trials in a large empty room in Oram’s Lace Mill. Although the air was still, the constraints of the space meant he had little room for error and so he ran the machine down a wire to ensure it was travelling in the right direction and at the right speed for take-off.

Even so, the first trial in the summer of 1848 ended in disappointment, the aircraft rising sharply, then stalling before dropping back on its tail. The second attempt saw the machine fly for more than ten yards at a speed of around 12mph before punching a hole in the canvas screen at the end of the mill. Stringfellow had flown the world’s first unmanned air vehicle.

His son, Frederick, had also caught the flying bug and together and individually they built several steam-powered flying machines. At the 1868 exhibition at the Crystal Palace, John demonstrated a triplane which got off the ground on several occasions and, for good measure, scooped first prize for his design for a six-unit boiler. Despite these successes, the onset of old age and his eventual death, in 1883, meant his dream of building a plane capable of carrying him aloft remained unfulfilled. 20 years later the Wright Brothers would eventually fulfil the dream of Dedalus and Icarus, proving the scoffers wrong, and winning the enduring fame which they still enjoy to this day.

Fame didn't elude Stringfellow entirely, however. While John Stringfellow’s achievements have long since flown under the world’s radar screen, there is a bronze model of Stringfellow’s machine in Chard’s Fore Street, various models are in the collection at the Science Museum in London, and — utterly bizarrely — his design was featured on a Cambodian stamp in 1987. What's more, the design he worked on with Henson essentially set the blueprint for aircraft design for decades.

Powered, manned flight did eventually come to Chard, on May 30, 1912, when the first aeroplane visited the town. Henri Salmet landing his Bleriot in front of a crowd of some three to four thousand. Even though the Frenchman was late, having followed the wrong railway line, he still found time to pay his respects at Stringfellow’s grave.

Credit: Getty Images

Jason Goodwin: 'My friend was puzzled to discover me up a stepladder, cradling my airgun and scanning vegetable beds'

Jason Goodwin takes on the rats, and loses.

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: The price of Absolute Power? Turns out it's £250 a week +VAT

An unforgettable week at the controls of a metal monster goes to Jason Goodwin's head.

The lost wonder of Concorde: A marvel, an inspiration and a 23 miles-a-minute gentleman’s club

Fifty years ago, Concorde first took flight and became a British icon. It was ahead of its time then –

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'Minette Batters explains why she's taken a job at Defra, and bemoans the closure of the Sustainable Farming Incentive.

By Minette Batters Published

-

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the world

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the worldWhere else on Earth can you find more than 752,000 acres of splendid isolation? Words and pictures by Luke Abrahams.

By Luke Abrahams Published