Curious Questions: Why do Australians call the British 'Poms'?

With England about to take on Australia in The Ashes, Martin Fone ponders the derivation of the Aussies nickname for us: Poms.

The one sporting occasion I always look forward to is the Ashes series, a contest fought out by the cricketing heroes of England and Australia. The rivalry on the field is intense and the spectators, their larynxes suitably lubricated by amber nectar, are quick to join in. To the Australians we English are Poms, a description usually bracketed at both ends by epithets, juicy, racy and pejorative. But why do the Australians call us Poms?

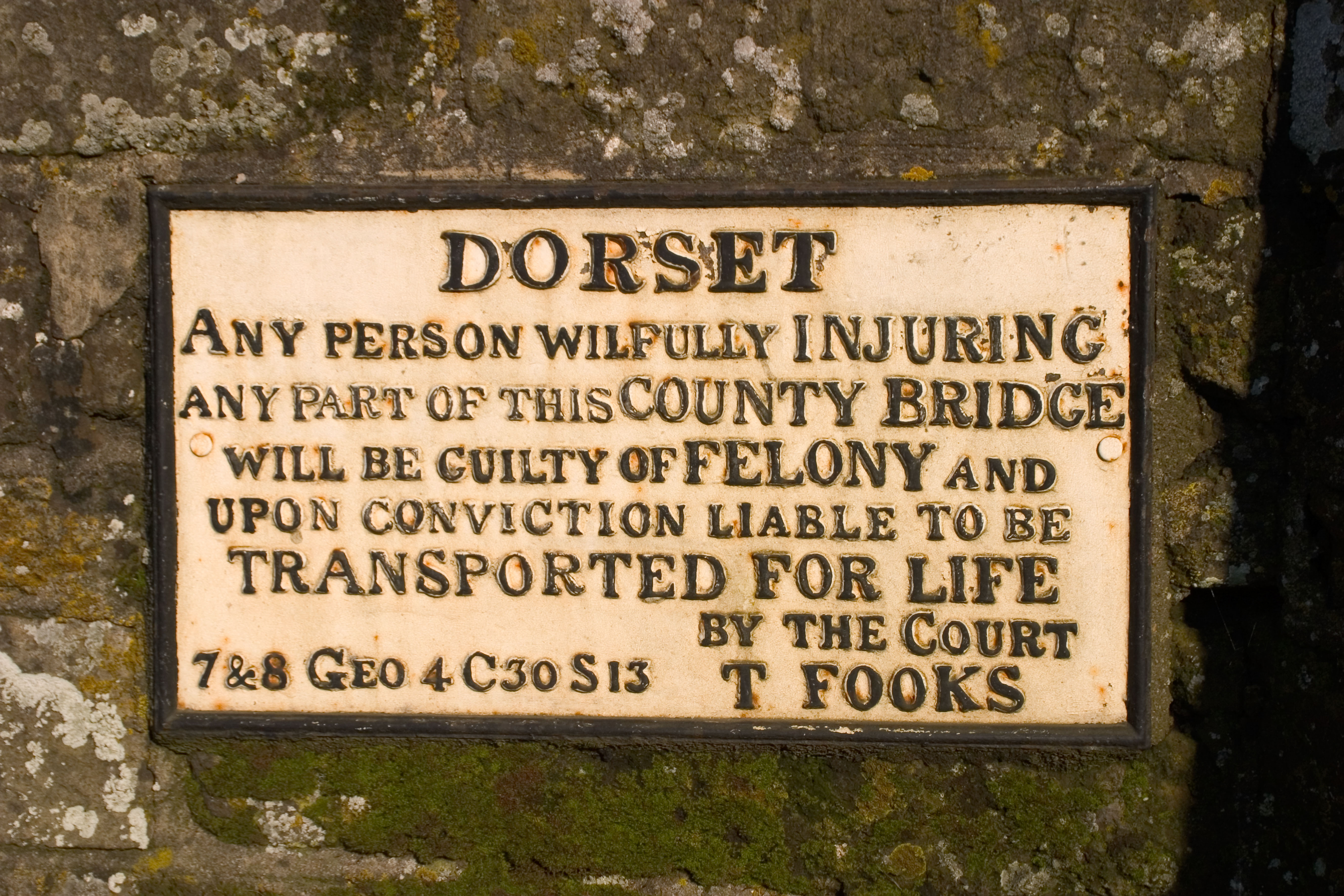

Once Captain Cook had ‘discovered’ the Australian continent and the British started to colonise it, to the understandable dismay and inconvenience of the existing aboriginal population, it was used as a dumping ground for what then were considered to be the detritus of British society. In truth, they were often little more than petty criminals: those who were sentenced to transportation to the other side of the world for seven years or more often received the punishment for what, to modern eyes, seem trifling misdemeanours.

Some 162,000 people were transported to Australia in the 80 years between colonisation and the punishment being outlawed, and the legacy of Australia’s convict past has been one that has been difficult to eradicate. Thus it is tempting to look to that iniquitous system for the origin of the term Poms.

There are lots of suggestions out there. Perhaps it is an acronym for Prisoner of Millbank, where many convicts were held before deportation, or Prisoner of His Majesty, or Prisoner of Mother England? The latter two are particularly unconvincing as an additional letter has to be swallowed up in the process.

Another theory is that it derives from Portsmouth, the port from which the convict ships set out, a city often known as Pompey. Perhaps the first syllable of the nickname gave rise to the term for Brits? Alternatively, it could be a reference to their port of arrival, Port of Melbourne?

I am troubled by these explanations. Why would the early settlers, the majority of whom were British, use a term which is intended to differentiate incomers from those who had been born and raised Down Under? It smacks of convenient retro-fitting to me.

Moving away from the world of convicts, another theory is that it is an abbreviation of pommes de terre, the spud being a staple and favourite part of the diet of the British troops during the First World War. Granted it was the first occasion that men from the two nations spent much time in close proximity but it requires a stretch of the imagination to think that the Aussies, inventive in their use of language as they are, made this linguistic jump. And, anyway, the term Pom was used before the Great War, the earliest instances cited in the Oxford English Dictionary dating to 1912.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

But if it is not the potato, it may well be another species of the plant world: Punica granatum — or the pomegranate, to you and I.

These fruits, between the size of a lemon and a grapefruit, have a characteristic which might hold the key: when they ripen in the sun, they go red — rather like the newly-arrived immigrants after they arrived, pasty-faced and somewhat green about the gills. After coming off the ships to be assaulted by the full force of the sun and Australia’s strong ultra-violet rays, newly-arrived Brits had a tendency to go red as lobsters and were easily distinguishable from the more sun-hardened, bronzed Aussies who had been there for a while and were acclimatised to the rigours of the climate.

The citations in the OED from 1912 show how ‘pomegranate’ became used to describe a newly-arrived immigrant. First, we need to understand a bit of the argot of the docks in Melbourne. Those with a penchant for rhyming slang called immigrants Jimmy Grants. Given their propensity to go red in the sun, perhaps some wag thought that a reference to the fruit would result in a more barbed insult. He may not have been wrong: ‘Now they call ‘em Pomegranates and the Jimmygrants don’t like it.’

A variation on the term is also recorded; ‘The other day a Pummy Grant was handed a bridle and told to catch a horse.’ As a nation the Australians rarely use polysyllables when one will do and so pom became the pejorative name for a newly-arrived British immigrant.

The Anzac Book of 1916 supported this theory, attributing ‘Pom’ as an abbreviation of pomegranate. The book’s author, Herbert J Rumsey, gave the theory some intellectual rigour in his book about the stream of immigrants seeking to make a new life in Australia, entitled The pommies, or, New chums in Australia, published in 1920.

The pomegranate theory was also good enough for D H Lawrence who repeated the story in his Australian-based novel of 1923, The Kangaroo, writing:

‘Pommy is supposed to be short for pomegranate. Pomegranate, pronounced invariably pommygranate, is near enough rhyme to immigrant, in a naturally rhyming country. Furthermore, immigrants are known in their first months before their blood “thins down”, by their round and ruddy cheeks.’

Perhaps it is right and at least it takes us away from the more dubious convict-era derivations. It was almost certainly a post-convict term but was also likely to have formed part of the every day speech of Australians well before the first examples appeared in print, perhaps dating to the nineteenth century.

These days, of course, Pom is used generally to describe a Brit, not just one who has newly arrived in Australia. I just hope that come the middle of September the Poms have their hands on the little urn once more.

Credit: Photo by FLPA/Hugh Lansdown/REX/Shutterstock – Bullet Ant (Paraponera clavata) adult, standing on leaf in rainforest, Tortuguero N.P., Limon Province, Costa Rica

Curious Questions: What is the world’s most painful insect sting – and where would it hurt the most?

Can you calibrate the intensity of different insect stings? Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions', investigates.

Curious Questions: What is the perfect hangover cure?

If there's a definite answer, it's time we knew. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions', investigates.

Credit: Rex

Curious Questions: Why do we still use the QWERTY keyboard?

The strange layout of keyboards in the Anglophone world is as bafflingly illogical. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher Published

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon Published