Curious Questions: Are Mothering Sunday and Mother's Day the same thing?

Mothering Sunday and Mother's Day have distinct meanings, as Martin Fone explains in the latest of his Curious Questions.

The advent of the fourth or middle Sunday of Lent must have been eagerly anticipated for centuries. Known variously as Laetare Sunday, from the Latin for rejoice, or Refreshment Sunday, from the text associated with the day, the feeding of the five thousand, it was the day when some relaxation of Lenten observances was allowed. Music played on an organ, flowers decorating the church and marriage ceremonies were all permissible. Worshippers were encouraged to visit their mother church, the church in which they were baptised or the area’s cathedral, a custom known as a-mothering, from which the day assumed another name: Mothering Sunday.

Mothering Sunday was associated with special foods, not least simnel cakes, which were often made by servant girls to give as a present to their mothers whom they visited on what was a rare day off, as Robert Herrick noted in his poem, A Ceremonie in Gloucester (1648): “I’ll to thee a Simnell bring/ ‘gainst thou go’st a-mothering;/ so that when she blesses thee,/ half that blessing thou’lt give me.” Looking rather like a pork pie in shape but with the constituents of a plum pudding encased in a stiff, hard crust, simnels were boiled for several hours, then brushed over with egg and baked. They were often stamped with the figure of the Virgin Mary.

Other dishes served on the day included frumenty — hulled wheat boiled in milk and seasoned with cinnamon and sugar — while in the north of England and Scotland there were carlings, a thick pancake made from pease, fried in butter, and seasoned with pepper and salt.

In Stottesden in South Shrophire, thick pancakes known as fraises were eaten with sweet sauces, while in Ludlow — according to the Shrewsbury Journal of March 26, 1879 — local butchers brought in a good supply of veal. A roast loin of veal followed by mincemeat and custard was a favoured repast amongst the better off while the lower orders made do with veal and rice pudding.

Although a correspondent of The Windsor and Eton Express was moved to declare in 1814 that Mothering Day observances had long died out in southern England, areas such as Shropshire and Cheshire still practised them well into the late 19th century. In Shropshire Folklore (1883) Charlotte Bume recorded that confectioners in Shrewsbury still made simnel cakes “in preparation for the family feast of Mid-Lent” and that they were “eaten by many who do not heed the pious habit of mothering which they were intended to celebrate”.

However, by the early 20th century the customs associated with the fourth Sunday of Lent had largely been forgotten, a state of affairs that Constance Penswick-Smith, the daughter of the vicar of All Saints church in the Nottinghamshire village of Coddington, set out to rectify. Her inspiration came from across the Atlantic after reading in 1913 about the campaign of Anna Jarvis.

“You take a box to Mother and then eat most of it yourself. A pretty sentiment.”

Two years after her mother’s death, in 1907 on the second Sunday of May, Anna held a memorial service in her honour at the Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church in Grafton, West Virginia. A second service was held the following year, on the same Sunday, at which white carnations were distributed to the mothers, sons, and daughters in attendance, while a much larger service was held in Philadelphia. The seeds of a new movement had been sown. A prolific letter writer and campaigner, Jarvis’ calls for a national day in honour of mothers gained traction, the governor of West Virginia making the second Sunday of May an official holiday.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By 1912 Anna Jarvis had founded the Mother’s Day International Foundation and had trademarked the phrases “Mother’s Day” and “second Sunday in May”. Her movement received the ultimate seal of approval when, in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson made the day an officially designated public holiday.

Constance Penswick-Smith, though admiring Jarvis’ efforts to establish a day devoted to honouring mothers, was concerned that her Mother’s Day was imbued with none of the Christian values associated with Mothering Sunday. She also regarded it as a superfluous addition to the calendar, her attitude encapsulated in a letter written to the editor of the Shields Daily News, published on May 14. 1927. “We already have our own Mothering Sunday,” she wrote, “which from time immemorial has been kept at Mid-Lent. Let us work for the revival of the true ‘Day in Parise of Mothers’ which is indigenous to this country. The whole is greater than its part, and Mothering Sunday gives all that the American ‘Day’ offers and much more besides.”

By the time Constance had penned these words, she had founded The Society for the Observance of Mothering Sunday which she based in Nottingham. To drum up support she designed and distributed Mothering Sunday cards to schoolchildren to give to their mothers, and wrote a play, In Praise of Mother: A story of Mothering Sunday (1913), A short history of Mothering Sunday (1915) which ran to several editions, and her most influential pamphlet, The Revival of Mothering Sunday (1921). She also produced a collection of hymns suitable for the day.

The Mothers’ Union, while supportive of the idea, considered that the custom had been dead for so long that any hopes of a revival were wildly optimistic. Nevertheless, Constance persevered, gradually winning over more and more of the clergy, ably assisted by the wonderfully named Rev Killer of St Cyprians in Nottingham and her four brothers, all of whom were priests. So successful was she that by her death in 1938, many parishes had revived the tradition of celebrating Mothering Sunday on the fourth Sunday of Lent. The Lady’s Chapel in All Saints in Coddington was dedicated to her memory in 1951.

Constance’s concerns that the American Mother’s Day was far too removed from the Christian values of Mothering Sunday proved well founded, with Anna Jarvis quickly realising that she had unleashed an enormous genie from the bottle in the form of rampant commercialisation. Card manufacturers, florists, and gift manufacturers were quickly alive to the opportunities that Mother’s Day presented, and, ironically, Anna spent most of the rest of her life campaigning against the very day she had done so much to create.

Anna started organising boycotts and was even arrested for disturbing the peace. Ready-made cards particularly attracted her ire. “A printed card,” she said, “means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world.”

Giving a box of chocolates was no better: “You take a box to Mother and then eat most of it yourself. A pretty sentiment.”

Christian sentiments were no match for the power of Mammon, though. With the enthusiastic and opportunistic support of businesses and shops hungry for revenue, Mother’s Day was a firmly established in the British calendar by the 1950s, although, unlike in America, it continued to be celebrated on the fourth Sunday of Lent.

Despite representing radically different concepts, the two names are nowadays used without distinction. What Constance and Anna would have made of it all is anybody’s guess.

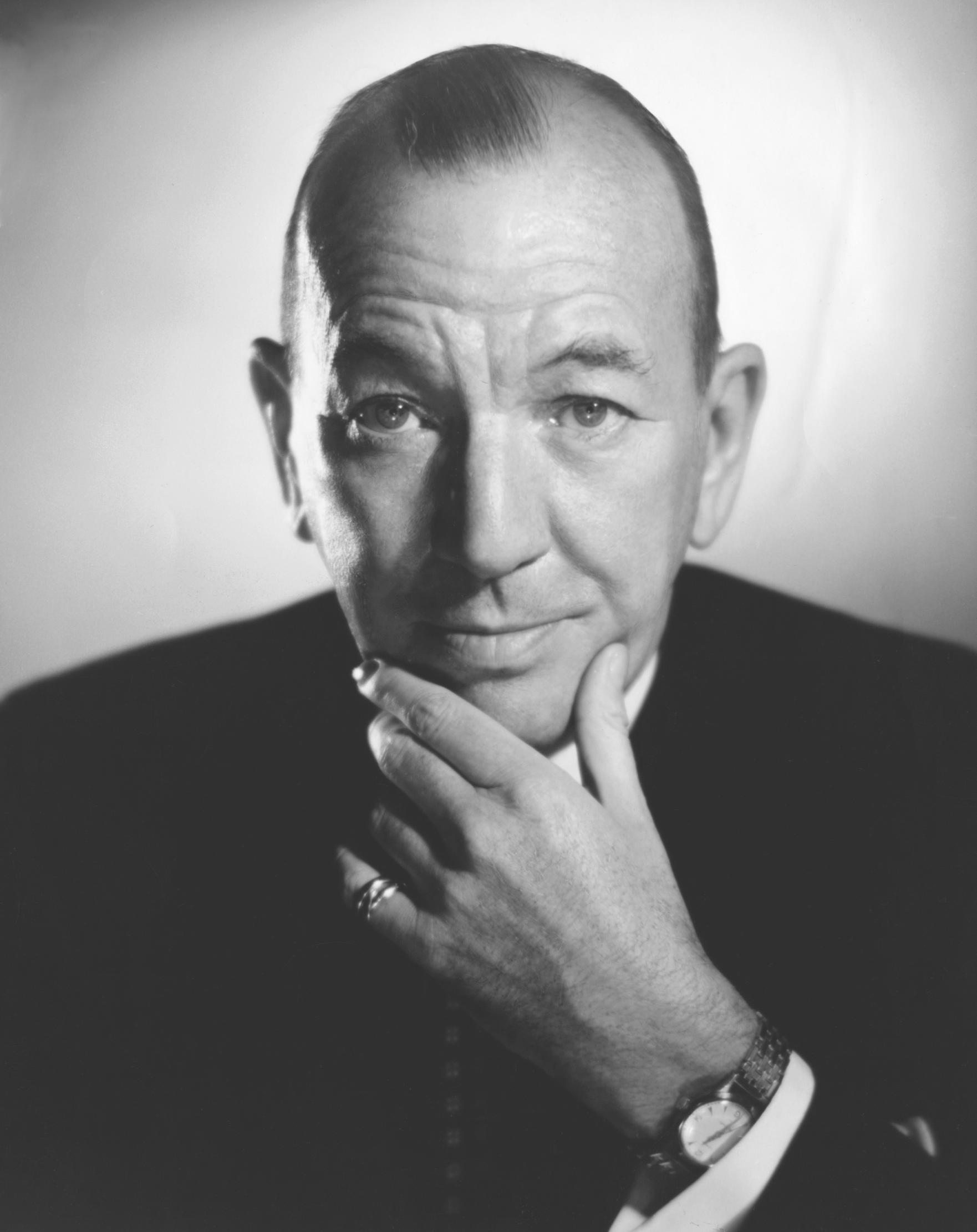

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

A woolly mammoth skeleton is among the curiosities for sale to save fire-ravaged Parnham Park

A woolly mammoth skeleton is among the curiosities for sale to save fire-ravaged Parnham ParkThe auction of the owner James Perkins' collection, hosted by Dreweatts, tomorrow (May 13), will be used to fund renovation works at Parnham Park in Dorset.

-

The ‘utterly unique’ skincare brand that’s used in the ‘world’s best hotel’ spa

The ‘utterly unique’ skincare brand that’s used in the ‘world’s best hotel’ spaThe Seed to Skin brand was the byproduct of one woman’s length fertility journey — it’s so good that today it’s used in a hotel voted the ‘world’s best’.

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

-

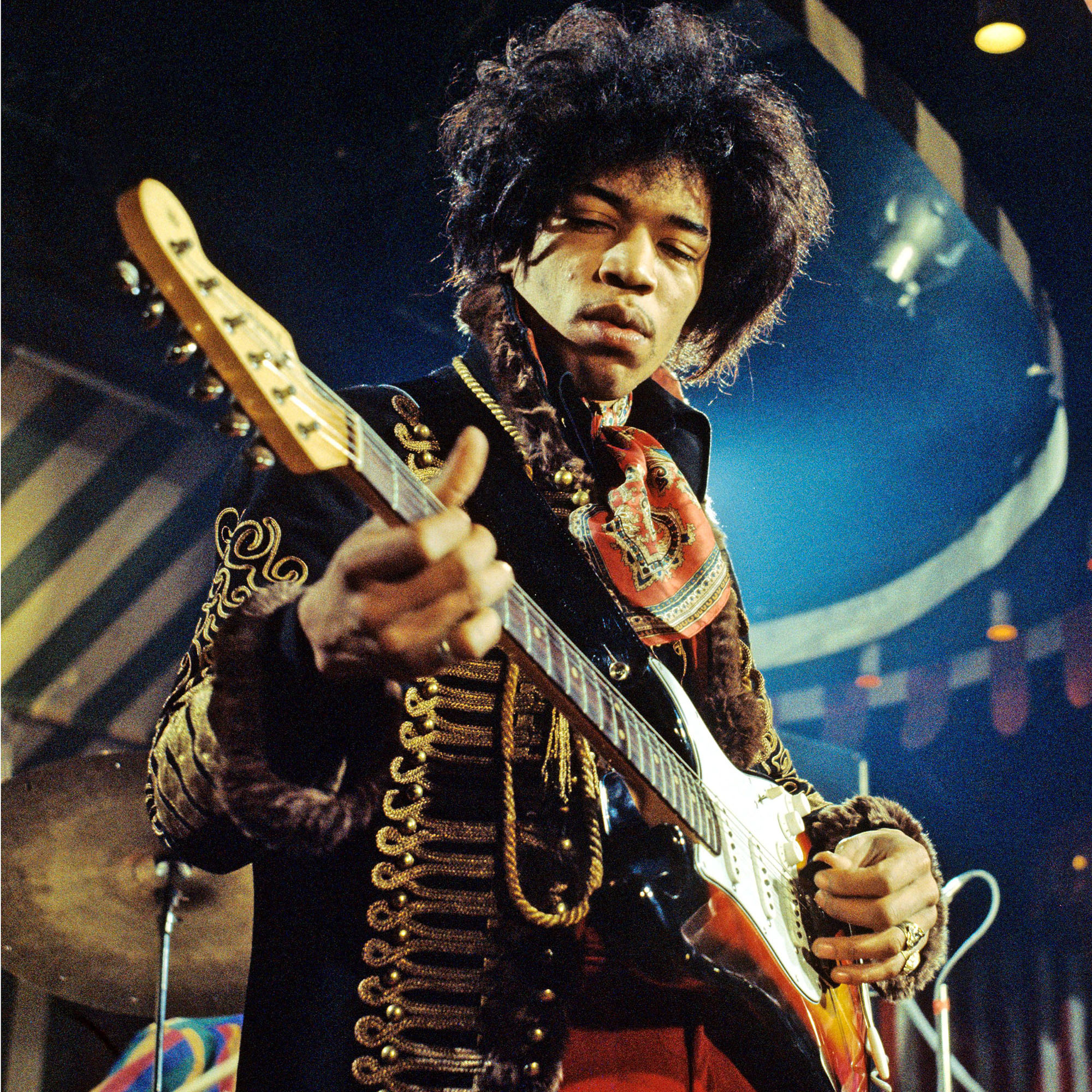

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.