Curious Questions: Would Anne Brontë be more famous without her two sisters?

To mark the forgotten Brontë’s 200th birthday, Charlotte Cory looks back at the life and works of this ‘runt of the literary litter’ and finds she was by no means meek and mild.

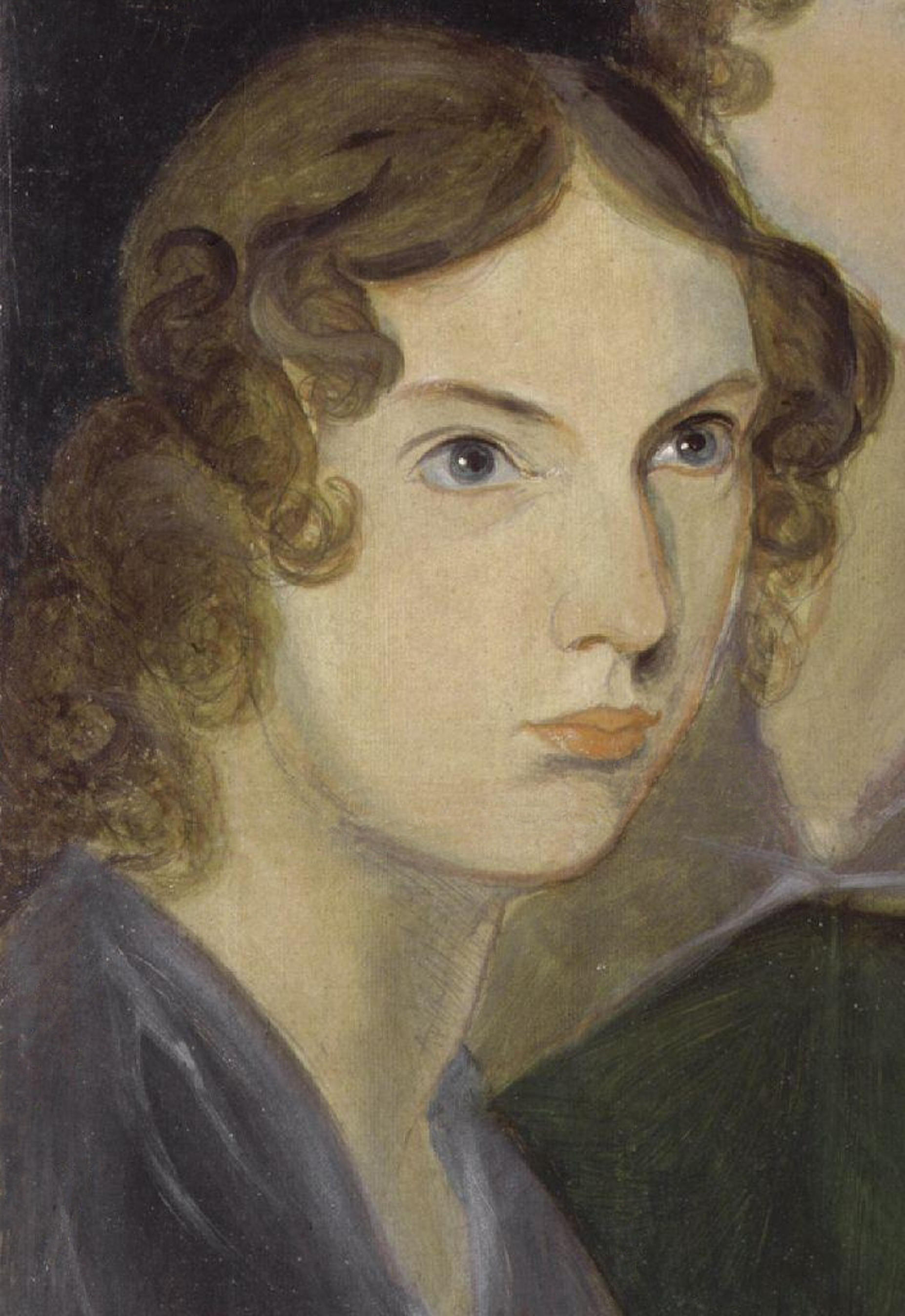

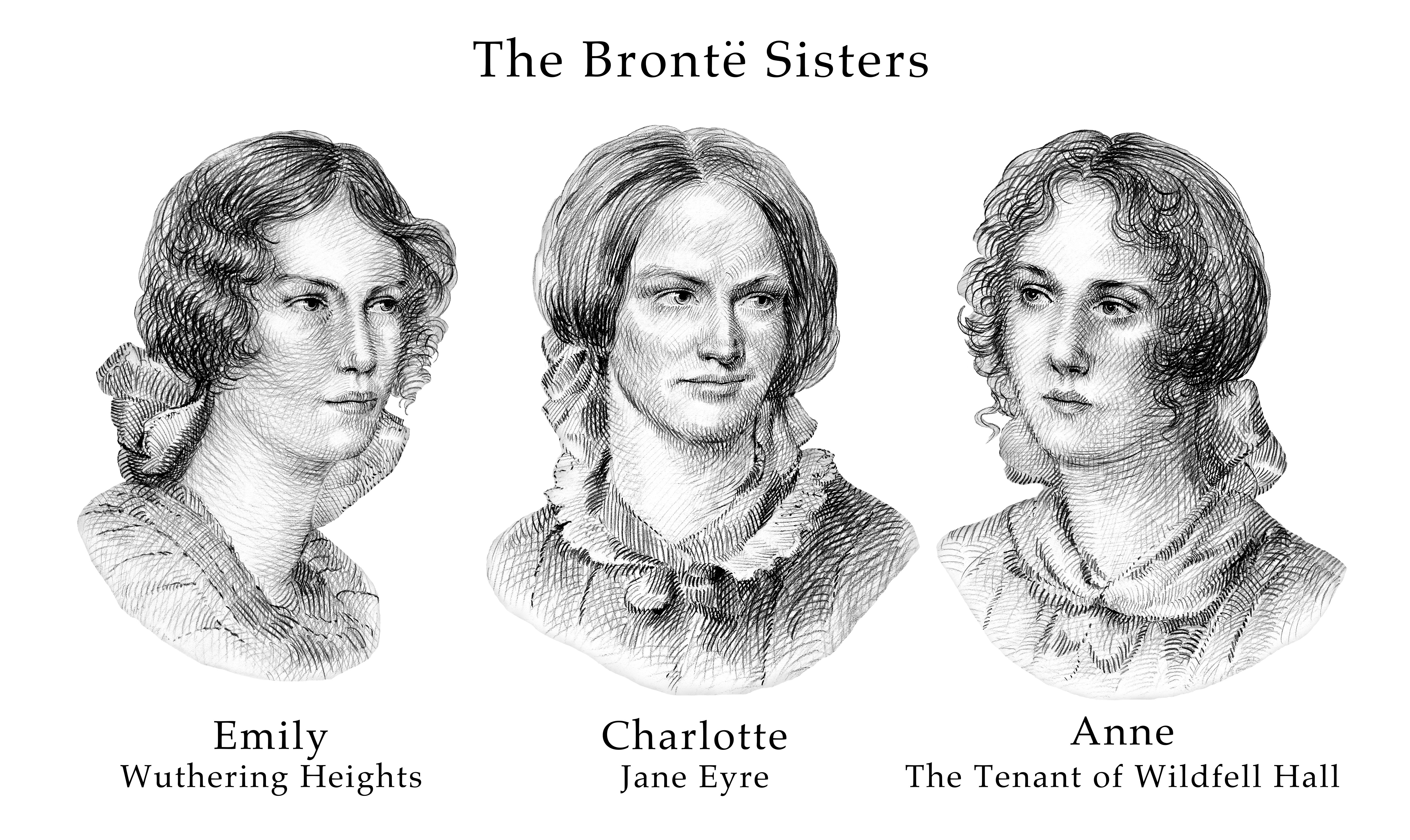

Pity poor Anne Brontë, the youngest, overshadowed and least read of the Brontë sisters. Regarded rather as the runt of the literary litter, Anne, like the last born in many large families, has always needed to elbow her siblings aside for the attention that is her due. It is her fate that The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, one of the first great feminist novels, is inevitably shelved alongside Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, two of the greatest novels ever written.

Anne was born on January 17, 1820, the sixth and final child of her Cornish mother, Maria Branwell, and Irish father, the Rev Patrick Brontë. A year later, Mrs Brontë became ill and took seven painful months to die, during which the six little Brontës huddled together downstairs, making no noise. Her despairing last words – ‘Oh God, my poor children’ – rang out through the quiet house although, throughout her illness, she had hardly seen them. As the first Brontë biographer, Mrs Gaskell, recounted, ‘the sight of them, knowing they would soon be motherless, would have agitated her too much’.

The problem of caring for the orphaned flock was solved when Mrs Brontë’s elder sister, Elizabeth Branwell, came from Cornwall to take charge of the household. Appalled by the Yorkshire weather, Aunt Branwell shut herself away in her room with the asthmatic, delicate baby Anne. She bolted the window, had a fire constantly burning and only left the parsonage on Sundays, to hurry across the churchyard and sit in the front pew of the church to listen to her brother-in-law preach.

Anne was four years old when her four elder sisters went away to the school for clergymen’s daughters, made infamous in Jane Eyre, and five when they returned, the two older ones to die and join their mother in the graveyard visible through the parsonage windows. Charlotte, now the eldest, appointed herself leader and formed a natural alliance with Branwell, the only boy, with whom she collaborated on stories set in the imaginary Kingdom of Angria.

Emily and Anne became so inseparable that people mistook them for twins. They, too, had their own fictional world, the Lands of Gondal and Gaaldine, developed in childhood and never set aside. They also wrote ‘diary papers’, a few of which survive, revealing their shared, secretive writing life that likewise endured for the rest of their days.

The creative yet claustrophobic parsonage was poor preparation for the outside world and each of the Brontës suffered wretchedly whenever they left home. Apart from a year at school, where Charlotte was a teacher, Anne’s first venture out was to become a governess – firstly with the Ingham family at Blake Hall in Mirfield, West Yorkshire, then for five years with the Robinson children at Thorp Green, near York. Unfortunately, she secured a job for her brother as tutor there and, when he formed an unwise attachment to Mrs Robinson, her husband sent him packing. Anne left, too. Branwell never got over his disappointment and, turning to drink and drugs, he made life miserable for everyone in the parsonage.

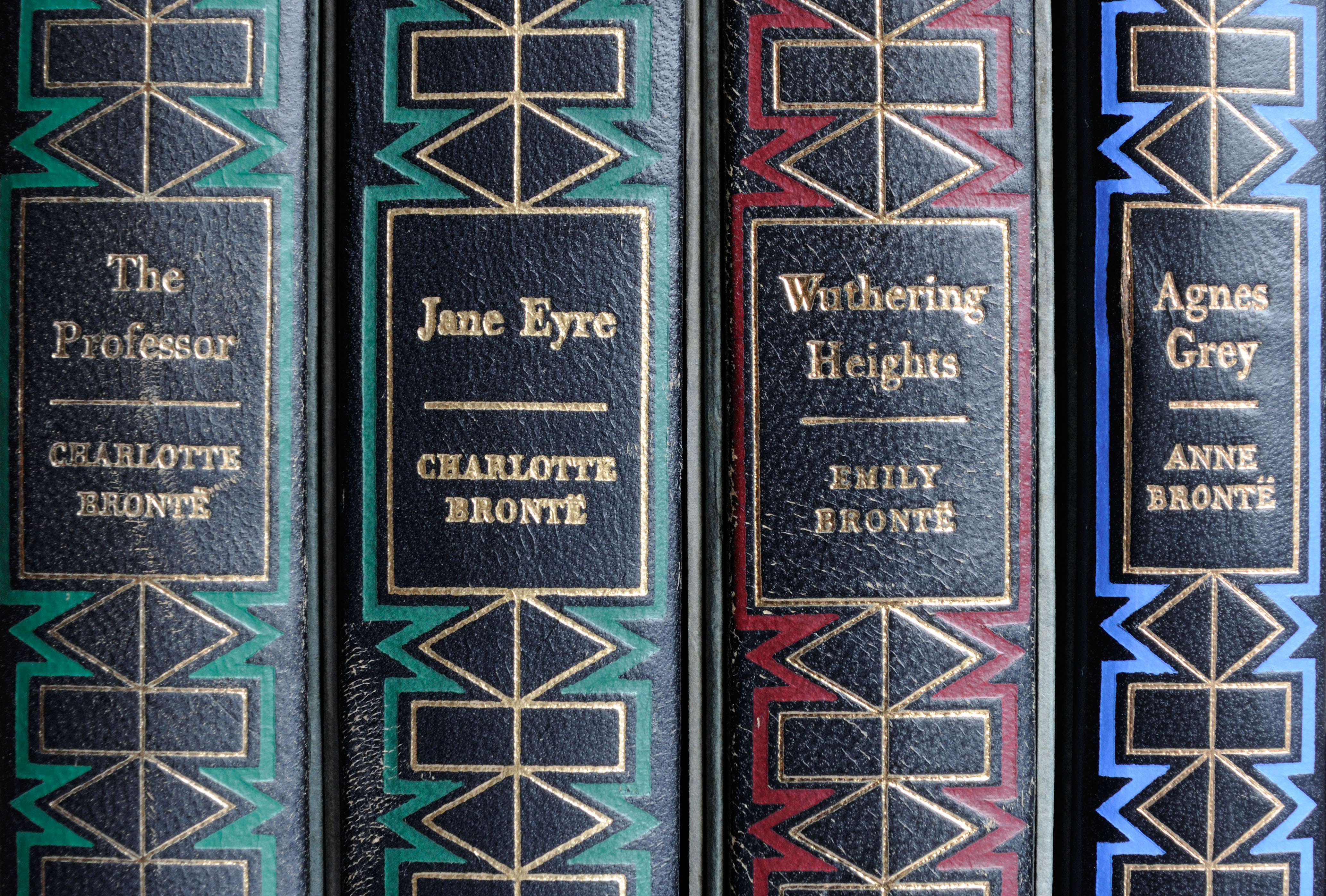

It was during this bleak period that Charlotte pushed her idea of publishing the sisters’ verse. After many attempts, she found a firm that agreed to issue The Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell (as the sisters called themselves), but at the authors’ expense. The sisters used their small legacies from Aunt Branwell and, although the venture was not a commercial success, it emboldened Charlotte to send their novels – her own The Professor, Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey – to publishers, who generally sent them straight back.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Eventually, a Mr Newby offered to publish Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey, again funded by their authors. Charlotte continued sending out The Professor and, when one firm turned it down, but said they would like to see more from Currer Bell, she immediately dispatched Jane Eyre. By return, they sent her a cheque and published it six weeks later. The enormous success of Jane Eyre galvanised Newby into rushing out Emily and Anne’s books in a single volume, full of typos, that did neither work any favours.

The reception of Agnes Grey was mixed: the authenticity of the experience of being a governess was admired, but the character of Agnes was too insipid for readers to take ‘much interest in her fate’. This book was inevitably compared to Wuthering Heights, largely praised for its ‘savage grandeur’, but also attacked vehemently for its amorality. Emily and Anne both suffered from this failure, but not enough to prevent them embarking on new novels. The following July, 1848, Newby published Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall as a new work by the bestselling Currer Bell.

'She was not buried in Haworth, but in a graveyard overlooking the sea'

Charlotte’s publisher wrote to Haworth demanding an explanation. In a panic, Charlotte made Anne accompany her to London to prove they were separate authors. Within weeks, Branwell died. Emily perished soon after and, when Anne learnt that her own tuberculosis was fatal, she insisted on journeying to Scarborough, where one of her last acts was to berate a man mistreating donkeys on Scarborough sands. Alone, of the whole tragic family, she was not buried in Haworth, but in a graveyard overlooking the sea.

As with Emily, the facts of Anne’s life are scant, largely edited by the domineering older sister Charlotte, who apparently burned letters and manuscripts in an attempt to protect her younger sisters from charges of moral turpitude. She tried to prevent The Tenant of Wildfell Hall being reissued, even though reviewers praised the startlingly unsentimental plot that challenged the idea of a dutiful wife standing by her husband, whatever his behaviour.

Anne’s death at the age of 29 deprived the world of an interesting voice. She wasn’t the meek and mild creature Charlotte would have us believe – the passionate honesty and liveliness of her writing and convictions make this youngest Brontë sister a fascinating character in her own right. Happy 200th birthday, Anne.

Inside Haworth: The humble parsonage where the Brontë sisters changed literature

Some of our most enduring stories were conceived at Haworth – Jeremy Musson enjoys a literary pilgrimage.

The house for sale where Charlotte Bronte and Elizabeth Gaskell forged their lifelong bond

Two of Britain's greatest novelists, Charlotte Bronte and Elizabeth Gaskell, shared a close friendship – and it all began at

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Five beautiful homes, from a barn conversion to an island treasure, as seen in Country Life

Five beautiful homes, from a barn conversion to an island treasure, as seen in Country LifeOur pick of the best homes to come to the market via Country Life in recent days include a wonderful thatched home in Devon and a charming red-brick house with gardens that run down to the water's edge.

By Toby Keel Published

-

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garage

Shark tanks, crocodile lagoons, laser defences, and a subterranean shooting gallery — nothing is impossible when making the ultimate garageTo collectors, cars are more than just transport — they are works of art. And the buildings used to store them are starting to resemble galleries.

By Adam Hay-Nicholls Published

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone Published

-

'It may be vain to think that the past was a cleaner, quieter and kinder place, but it felt pretty decent when you knew your GP and your GP knew you, and milk in glass bottles was delivered every morning'

'It may be vain to think that the past was a cleaner, quieter and kinder place, but it felt pretty decent when you knew your GP and your GP knew you, and milk in glass bottles was delivered every morning'Carla Carlisle is homesick for the olden days, when we didn’t know we had it so good.

By Carla Carlisle Published

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes Published

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins Published

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone Published

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone Published

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone Published

-

Patrick Galbraith: We are a brilliant and terrible species who messed it up a long time ago — and that means we have to do things we don't want to

Patrick Galbraith: We are a brilliant and terrible species who messed it up a long time ago — and that means we have to do things we don't want toOur columnist laments the painful decisions on culling wild animals which he argues have to be taken if we're to manage the countryside and maintain biodiversity.

By Patrick Galbraith Published