Carla Carlisle: 'I’m about to expand on my belief that reading fertilises our memories and allows us to visit our past without getting hurt when I see her eyes wander off towards Monty Don'

Books create a powerful connection with the home of your youth, finds Carla Carlisle.

I am shuffling books in my bookstore when a customer comes up to me. Peering over her mask, she says: ‘I guess you haven’t been back home during all this. Do you get homesick?’

It’s a friendly question that deserves a friendly answer. I’ve learned that most folks don’t expect a diatribe about the state that believes Donald Trump won the last election. They don’t want to hear the heart-breaking news that Mississippi is the first state to reach the morbid milestone of losing one in every 300 residents to coronavirus and that, if Mississippi were a country, it would have the second-highest per capita death rate in the world, just under Peru. They only wonder if I miss home.

Remembering my manners, I call on Eudora. For more than half a century, Eudora Welty chronicled Mississippi with a truthfulness that was easier for me to latch onto than the intense and entangling chronicles of William Faulkner. Both writers had longish spells out of the South, but both writers came back to their birthplace. Their roaming likely ignited the eternal truths they found in their postage-stamp universe.

It’s in this spirit that I turn to Welty, who wrote that: ‘A place that ever was lived in is like a fire that never goes out.’ I say that I don’t miss the heat, that I like picking blackberries in Suffolk because I’m not on the lookout for snakes. I make cornbread in my grandmother’s black iron skillet and grow my own tomatoes. The ones that don’t ripen I dip in egg and cornmeal and fry. I also proudly claim to be bilingual: long ago, I surrendered gas stations and sidewalks, but I talk to my chickens in the pure Southern voices of my great aunts Edna and Blanche.

This wistful journey down Memory Road takes place next to a table that includes books by Flannery O’Connor (Georgia), Ann Patchett (Tennessee) and Faulkner.

I point to the slender volume The Optimist’s Daughter. ‘Welty got the Pulitzer Prize for this in 1973,’ I say. ‘I love it. I read it once a year and it’s like a trip home.’

I’m about to expand on my belief that reading fertilises our memories and allows us to visit our past without getting hurt, when I see her eyes wander off towards Monty Don over by the gardening table.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

I can tell that I’ve given her more than she asked for. I could have told her that talking to strangers is a Southern thing.

As I’ve got older, I’ve come to believe that a force more potent than homesickness is the old story of temps perdu. It grows as slowly as a tree and it’s in the realm of ‘what if?’. Whenever I read Welty, I can’t help wondering: ‘What if I’d gone back to the South like she did? Would I have buckled down and become a serious writer if I’d stayed put?’

"During lockdown, I made a journey homeward — it just happened to be at the bottom of the farm drive, where I spent my days in a small cottage cataloguing the library of some 400 books on the South and the Civil Rights movement"

It’s not only when I read Welty’s work that I feel like this. This week, a proof copy of Miss Patchett’s new collection of essays arrived. I read them all in a day and a night and then succumbed to an acute case of the ‘what ifs’, triggered in part by our parallel lives. Miss Patchett lives in her hometown of Nashville, but she went to a small liberal arts college called Sarah Lawrence in New York (so did I). She was the only Southerner there in her day and, 16 years earlier, so was I, although I overlapped with the writer Alice Walker (Georgia) in my first semester. In those days, Southern girls in this New England setting stuck out a mile.

As I read the essays, I kept thinking of all we had in common (did I mention that she also has a bookstore?) and lost track of the differences. For instance, I grew up in the South of civil-rights turmoil; I was in college during the war in Vietnam. Timing powerfully defines our lives. So does biology. She has the precision and discipline of a Swiss watch; I’m easily distracted. I might add that she hates mess, practises Kundalini yoga, is a vegetarian and teetotal. I fall asleep during Pilates class. I raise sheep and like lamb pink with rosemary and garlic. I planted a vineyard on a south-facing slope on a farm in Suffolk. Even if I’d spent my life surrounded by cotton fields in the Mississippi Delta, I wouldn’t have (make that: couldn’t have) written Bel Canto.

Miss Patchett’s new book is called These Precious Days, after the final essay she wrote about the first lockdown. The title itself feels prayerful. It also reminded me why I’m not homesick. During lockdown, I made a journey homeward — it just happened to be at the bottom of the farm drive, where I spent my days in a small cottage cataloguing the library of some 400 books on the South and the Civil Rights movement. The collection includes photographs of Mississippi, five taken by Welty in the 1930s and eight in 1961 by Martin Dain.

In the evenings, I read. I began with the novel I wrote when I was 16, called Mildew on the Magnolias, but I only got halfway. Instead, I finally read all the novels by Faulkner I’d never read. Rather like our memories of the places of our past, I’d always liked the idea of Faulkner better than the actual books. Reading him late in life finally cured that.

Those precious days revealed a lot of things. Above my desk is a photograph I found in Oxford, Mississippi, 30 years ago. It was taken in New York in May 1962 when Welty presented Faulkner with the National Institute of Arts and Letters’ Gold Medal for Fiction. She tells her fellow Mississippian: ‘Mr Faulkner, I think this medal, being pure of its kind, the real gold, would go to you of its own accord, and know its owner, regardless of whether we were all here to see or not. Safe as a puppy it would climb into your pocket.’

It serves as a poignant reminder that our sense of place is safe as a puppy and rests in an invisible pocket. Whether we know it or not.

Carla Carlisle on pirates

Carla says her bite is worse than her bark as she watches aghast at everything from Bernard Madhoff’s behaviour to

Credit: De Agostini via Getty Images

'It took my son and daughter-in-law a weekend to set up an online shop... In a week, we sold £10,000 of wine that was languishing in the bonded warehouse'

Carla Carlisle's lockdown has taken her farm shop to places she'd never imagined — but now she's there, she's not

Carla Carlisle: 'Something happened: instead of celebrating the solitude and bounty, I became haunted by the inescapable inevitability of dinner'

Carla Carlisle took enthusiastically to the first lockdown, but found herself languishing during the second one.

Credit: Alamy

Carla Carlisle: 'We took it for granted that we could travel the world and live wherever we wanted... Now the dice is loaded against our children and against the planet. What were we thinking?'

Carla Carlisle on being a pessimist, making lists, and seeing snow for the first time.

Credit: Alamy

Carla Carlisle: 'Maybe we have to accept that dogs share our rage at growing old'

In a heart-wrenching column, Carla Carlisle talks about the sadness of dealing with dogs who don't go gently into the

Credit: Alamy

Carla Carlisle's A to Z of uncertain times: 'Never talk about money to those who have much more or much less than you'

Carla Carlisle: 'It sounds tactless, but I’ve long believed that the most beautiful word in the English language is "cancelled"'

Raging against the lockdown isn't for Carla Carlisle, as she admits to 'a swoosh of contentment' whenever she thinks about

Monty Don: How to stop worrying and learn to love gardening in November

November can be a depressing time for gardeners – but not if you dive in and make the best of it,

Monty Don: The point of gardening? It's to find solace, to be happy, to make beauty, have fun and muck about. How you do it doesn't matter.

Monty Don, gardening writer and broadcaster, speaks to Country Life’s Tiffany Daneff about dogs with film presence and the lockdown

The Gardens at The Manor, Priors Marston: A house bought on a same-day impulse that became a 20-year labour of love

The inspiration for the garden of The Manor, Priors Marston, Warwickshire, was to create a landscape to meander through, with

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill

-

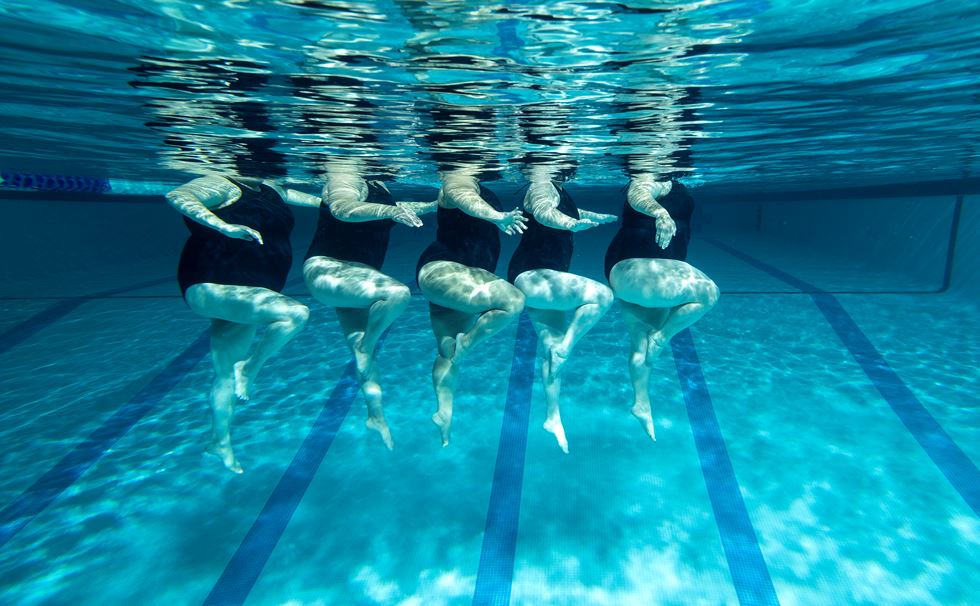

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes