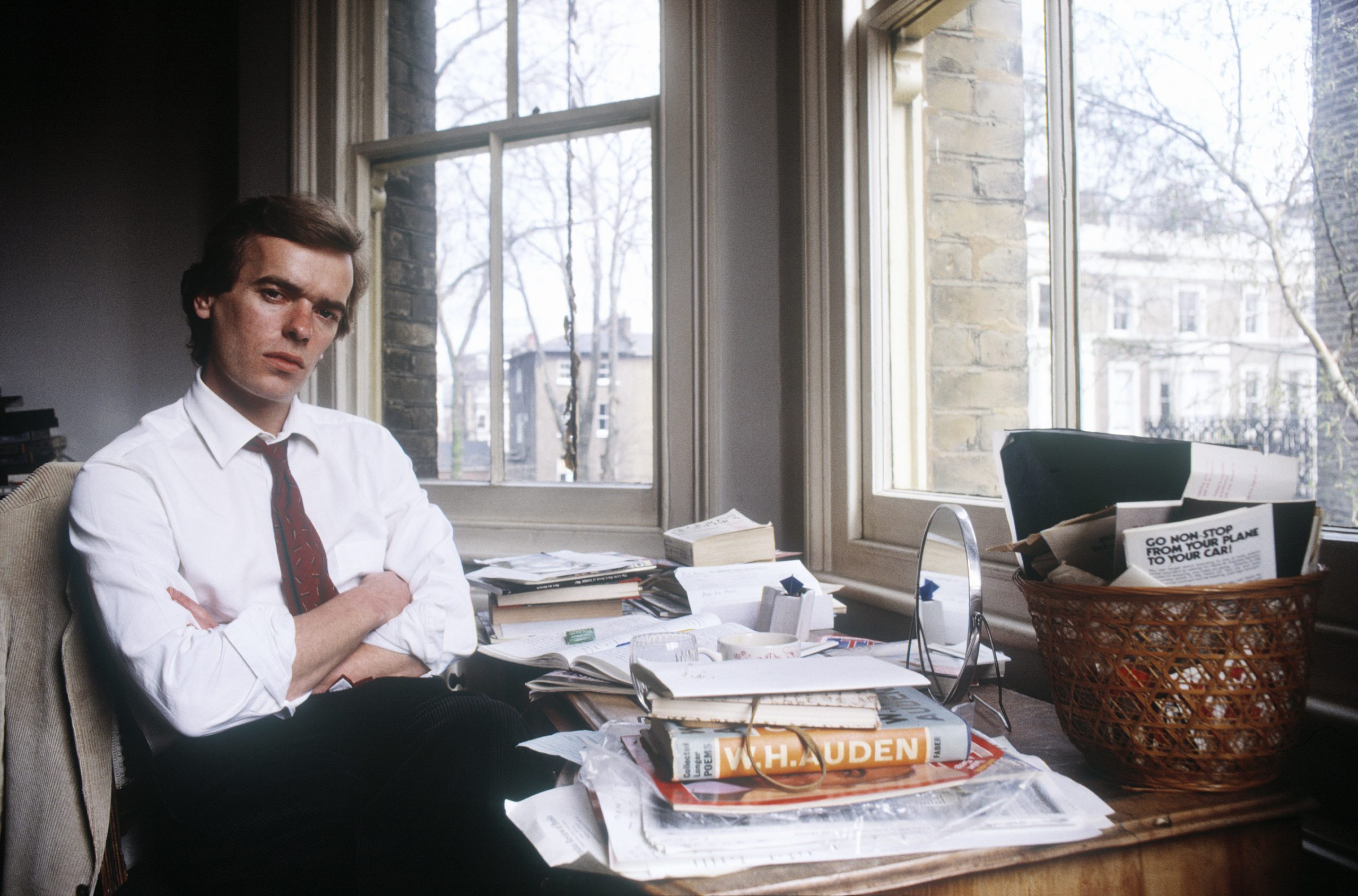

Carla Carlisle on Martin Amis: The 'passionate, graceful, fierce' writer who scared us, challenged us, and brought us understanding

Carla Carlisle pays tribute to the late Martin Amis, who died last month.

Towards the end of his life, Chekhov said that everything he read seemed to him ‘not short enough’. I know the feeling, and I’ll try to keep this short. When the Russian writer said that I don’t know — I heard it from Martin Amis who, when asked about ageing, agreed with Chekhov.

Amis was referring to writing, however, not reading and not to life. Although he feared the ‘tsunami of old people’ occupying the land, he wasn’t personally ready for the euthanasia booths on street corners providing the ‘martini and a medal’ that he once proposed as the noble exit route for the elderly. Like most enfants terribles, he was pretty confident that he would avoid the civil war between the young and the old that he saw coming.

When I heard Amis had died — the lead news on Today at 6am on May 20 — the announcer added, as they always do, ‘age 73’, my first thought was: he concocted his exit potion of choice. Amis claimed that he started smoking at the age of 10 and he was rarely photographed without a roll-up and a whisky, the same poisonous brew that ended the life of his closest friend, fellow writer and agent provocateur Christopher Hitchens 10 years earlier, aged 62.

Without checking the archives, I think it is safe to say that Amis, ‘Britain’s most famous literary son’ (New York Times obituary, May 22), didn’t show up regularly in the pages of Country Life. Why would he? His novels are largely urban tales with emphasis on the messiness of life, love, sex and money. There were a few bucolic detours — he had happy childhood memories of an interlude in South Wales when it was still Cider with Rosie country — but the iridescent and sympathetic complexity of country life was not his world.

Before heading to the kitchen for coffee, I went to my bookshelves. I found only one volume by Amis: The Rub of Time, a collection of his non-fiction: essays, literary criticism, reviews. Where was his memoir Experience? The essays The War Against Cliché? Had they strayed to bedside tables in guest rooms? I didn’t search for the novels, which I often found ‘not short enough’, but his essays are passionate, graceful, fierce.

"He was horrified by the ‘cancel culture’ that now infects both countries: ‘Every fibre in my being resists. It’s a philistine manifesto. It’s anti-creative'"

My single Amis volume was almost eclipsed by a row of fat volumes by Hitchens, better known as ‘Hitch’. Fellow ex-patriots, literary soul brothers and friends through thick and thin, which includes Hitch’s polemics on the Iraq war, Mother Teresa, Ralph Nader, Hillary Clinton and God. Over the years, Amis disagreed violently with his friend in print, but never fell out with him personally. It was a lesson Amis said he’d learned from his father, Kingsley: ‘He lost a lot of friends over Vietnam, great friends. You can’t afford that. As Hitch said, you can’t make old friends.’ Both of the writers held an obvious fascination for me. Long before I settled into this space under the agreeably ambiguous banner ‘Another Country’, I shared with them the expatriate journey, in reverse.

Even before Amis exchanged his house in Camden for the brownstone in Brooklyn, his was the gaze of an exile who captures the Old Country with a ferocity that those left behind read with apprehension and dread. I remember seeing his 2012 novel, Lionel Asbo: State of England, described in Hatchards as a ‘grotesque version of modern-day Britain under the reign of celebrity culture’, and wondered who thought that would boost sales. The reviews put Amis on the defensive. In an interview with Jeremy Paxman, he insisted that the novel was not an attack on England: ‘I am proud of being English.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Of course, for all their Americaphillia, Amis and Hitchens knew they were lucky to be English. Both born in 1949, both Oxford graduates (Hitchens, Balliol College; Amis, Exeter), they were revered in America for their scholarly writing and their beautiful Oxbridge accents and rich baritones. They both expressed their dazzlingly digressive ideas with a fluency that left their audience spellbound. The prophetic Amis was not recognised in his old homeland, however. He won the Somerset Maugham Award for his debut novel The Rachel Papers in 1973, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Experience in 2000, and nothing between or after. The critics in his homeland were pious and merciless. Even the English obituaries felt snide, stooping to cracks about his diminutive height and stratospheric dental bills, expenditure any half-wit American would consider a better investment than a designer kitchen.

If changing countries freed him from constraints and judgements that were distracting and demeaning (those teeth again), he knew there was no Utopia. He hated what Brexit said about Britain, but he thought what Donald Trump said about America was worse. He was horrified by the ‘cancel culture’ that now infects both countries: ‘Every fibre in my being resists. It’s a philistine manifesto. It’s anti-creative.’ If future students are allowed to read his novels, they will require a ‘safe space’.

Long before the phrase existed, Amis was accused of being a ‘nepo’ kid. That was particularly bad luck as his famous writer father never gave his son any literary encouragement. In his memoir, Amis wrote of his gratitude to the stepmother Elizabeth Jane Howard who gave her near-illiterate 15-year-old stepson a volume of Pride and Prejudice and said: ‘Read this!’ It was the turning point in his life and he credited Howard for making him a reader, which made him a writer.

Writers like Amis tell us things that are important, things that scare us, things we don’t want to think about and, sometimes, things that bring understanding. They also remind us that there comes a time when what we read and what we write is ‘not short enough’. The good news is that we are not alone.

How to cure a hangover, by some of Britain's greatest-ever writers

Got a hangover? Heave yourself out of bed and throw yourself on the mercy of one of these literary cures,