Carla Carlisle: 'Seamus Heaney deserves a sainthood, as well as his Nobel Prize'

Carla Carlisle applauds The Letters of Seamus Heaney and shares how she couldn't wait until Christmas to devour the collection from the late Irish poet

Early in December, my husband asks me: ‘What would you like for Christmas?’

Every year, I say: ‘I have everything I want.’

And it’s true: every room, cupboard, surface in this house is covered in stuff. It’s like the house in the Somerville and Ross novel The Big House of Inver: ‘Under everything there was something’ — and, in this house, it is papers and books.

This year, I was able to reply: ‘I want The Letters of Seamus Heaney.’ It was on order for the bookstore that occupies our old dairy, so it had another advantage, it would be easy for him to procure.

Then something happened. As soon as the box of The Letters arrived, I knew I couldn’t wait four more weeks. Although it meant that I would deprive my husband of the peace of knowing his ‘present dilemma’ was solved, I couldn’t let go of the book. I added it to my shop bill, wrapped it in my sweater and, with it safe as a puppy, I carried it home.

There was no chance of hiding it: The Letters has the heft of a piece of farm machinery. It is also a beautiful book: very good paper, pages sewn so it opens out gracefully onto the table — this is not a book to read in bed. Straightaway, you feel you will be guided by the sensitive and scrupulous editor.

"He believed that being poet was a preoccupation, not an occupation"

Christopher Reid, a poet himself, was formerly Heaney’s editor at Faber & Faber and this is a remarkable achievement. In the summer of 2007, Heaney wrote to him after reading the Letters of the poet Ted Hughes, which Mr Reid had recently completed editing. ‘Your introduction has perfect pitch — true to the friendship, to the editorial requirement, close, kind, grave, loyal and loving.’ I don’t think Heaney anticipated him editing his own letters, but all he wrote can be said about Mr Reid’s introduction to this volume.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It is not a quick read: more than 800 pages and, even with that plenitude, Mr Reid admits that he ‘had to cut back severely to make a book of publishable proportions’. Absent from the collection are the letters Heaney wrote to his wife, Marie, and their three children, Michael, Christopher and Catherine.

One suspects that those letters would be a tender treasure trove: Heaney spent months each year in the US, first at Berkeley, then long stints at Harvard, always trying to pay the rent, then the mortgage, placate the bank manager, support his family. The reader may wish for the love letters, but his love for his wife and family is all through this collection.

In the very first letter, December 9, 1964, he writes to his friend, fellow poet and Northerner Seamus Deane: ‘Now to minor matters. I got engaged a fortnight ago to Marie Devlin and hope to be married next August. We are very happy and believe we can remain so for a lifetime… I met her two years ago and knew from the beginning that she was the girl to hunt — but now she is not so much a quarry, more way of life.’

He wasn’t a poet when they met, something Marie thought was a ‘good thing’. Heaney would have agreed. Long after he was being called ‘the best Irish poet since Yeats’, he remained gently superstitious. He used ‘poet’ to describe others, applying ‘writer’ to himself. When he filled out landing cards, under ‘occupation’, he wrote ‘teacher’ or sometimes ‘writer’, never poet: ‘I’m too superstitious and religious.’ He believed that being poet was a preoccupation, not an occupation. Until you win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Reading the letters of writers can feel intrusive, but, as well as being a map into the writer’s life, it is a lens into the writing life. Heaney’s letters show the complicated balancing act of earning a living, raising a family and making space for the ‘work’. The letters also show what a saint the man was. A letter to his friend, the artist Barrie Cooke, is memorable: ‘In the last two days I have written thirty-two letters… The trouble is, I have about thirty-two more to write: I could ignore them but if I do the sense of worthlessness and hauntedness grows in me, inertia grows…’

"Heaney deserves a sainthood, as well as his Nobel Prize"

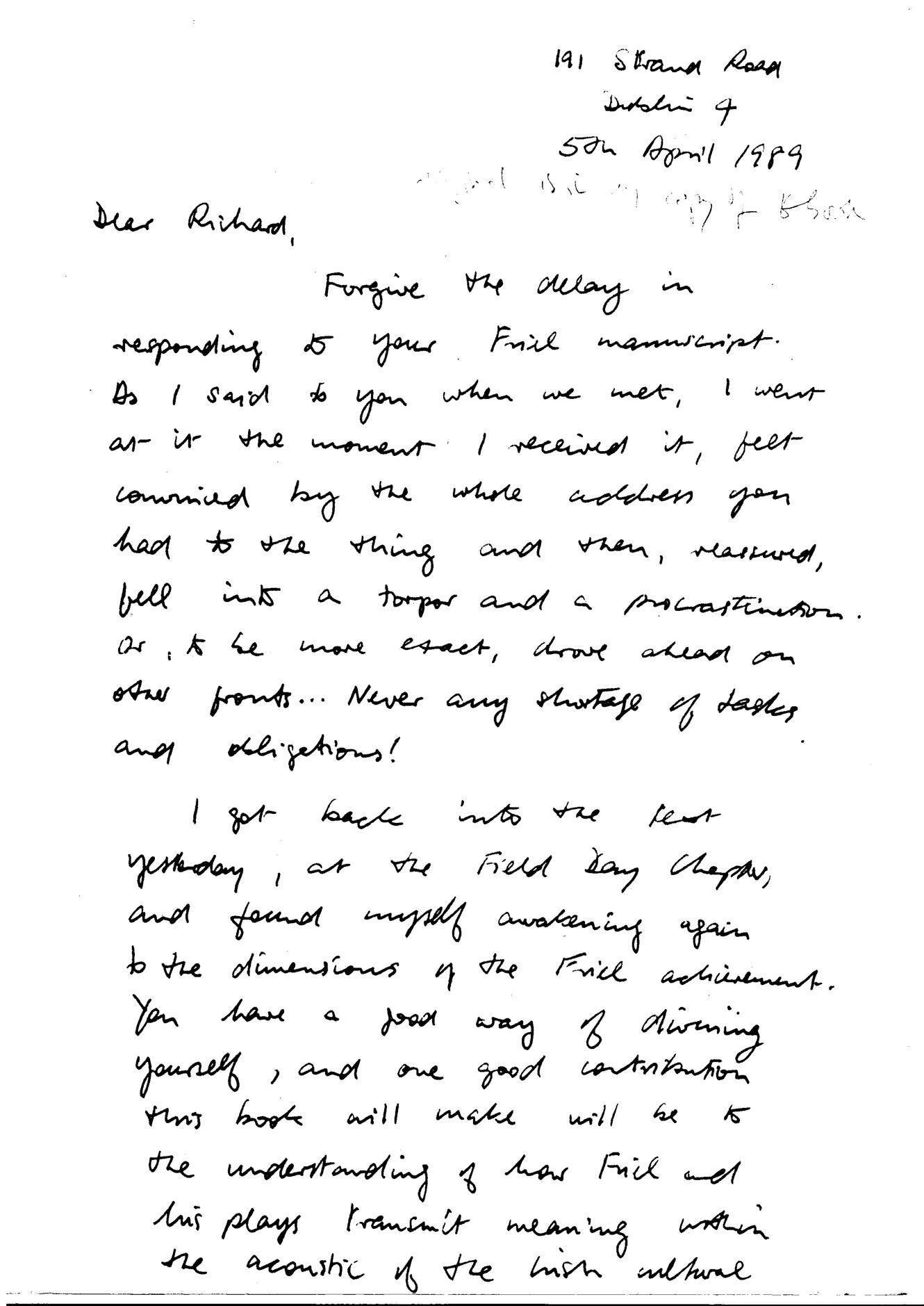

I read those lines aching for Heaney, a poet so genuinely kind, generous and sensitive, that he feels honour bound to answer letters. And then, suddenly, I felt a small patch of relief. I, too, have a letter from Heaney. Not collected here in The Letters, but one written after I’d interviewed him in his home in Dublin for The Washington Post back in the autumn of 1981. As do so many of his letters, it begins with an apology: ‘...a little shamefaced and tail-between-the leggish’, then an account of the family’s two weeks in the Dordogne after a stay with me in Paris that included our exchange of books by the widow of the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam.

I’m not an archivist, a saver of letters. Nothing amazes me more than the vast collections of poets’ letters, something that will vanish in the age of email. Thankfully, I saved my Heaney letter, together with a handwritten poem, The Easter House, which he left for me in the flat in Paris. Written in his ‘brown-ink’ period, it has faded a little, but, at some point, I framed it, which I hope helped it to survive.

I didn’t keep in touch with Seamus and Marie. Reading these letters, I remembered why. In his study at the top of the house where much of the interview took place, I saw the stacks of to-be-answered letters that haunted him. Heaney deserves a sainthood, as well as his Nobel Prize, for the many thoughtful, generous, kind and time-consuming letters he wrote during his all-too-short lifetime. Without them, we would not have this rare and precious volume, which is an enduring life of a great poet and a truly good man.

Are these the seven best independent bookshops in Britain? A writer makes her case

Jonathan Self: The simple key to a life full of joy and happiness and free of care

An encounter with a 21st century goatherd makes Jonathan Self wonder if things might one day again be simpler.

Credit: Getty Images

Carla Carlisle: 'I think I sound as English as Judi Dench, but strangers still ask “where are you from?"'

Our columnist Carla Carlisle bumps in to a milestone in her life, prompting her to take a look at the