Country Life's Christmas message, from The Bishop of Leeds: 'I wish everyone – the faithful and the faithless – a happy and earthy Christmas'

The Bishop of Leeds, The Rt Revd Nicholas Baines, talks of the relevance of the Christmas story to all and why everyone is welcome at church.

Don’t ever mess about with Christmas carols. I once got into big trouble for making a suggestion in a book that I still think is perfectly reasonable. I proposed changing the words of O Come, All Ye Faithful to O Come, All Ye Faithless.

Why? Well, simply because a quick look at the original Christmas story in the gospels makes it clear that the people who first encountered the baby in the manger at Bethlehem were not the usual suspects.

Shepherds were people who got on and did the work so the more religiously rigorous flock owners could do their devotional duties. They were more like outsiders – not considered the most clean people in society. Magi were foreign astrologers, whose curiosity led them to embark on a journey that took them into the dark heart of violent politics in a place where they were regarded as suspect. Mary herself was an unmarried mother who would soon be subject to gossip, persecution and exile.

'We are no more exempted from all that the world can throw at us than God himself'

In other words, the first Christmas seems to present us with a surprising group of people whose familiarity to us has led to a blunting of the shock we are supposed to feel. It was, I suggest, the faithless (Mary excepted, of course – you have to read her story) who came to the stable and not primarily the faithful.

This is the element of surprise that can and should accompany Christmas even today, even in a distant culture and a society a million miles from 1st-century Palestine. The Scottish musician and liturgist John Bell captured this in a song that contains the line: ‘God surprises Earth with Heaven, coming here on Christmas Day.’ In this baby, born subject to all that living in a frightening and mortal world can throw at him, we are all invited to look around the corner of our securities and be surprised that God is for us. And that is why it is the faithless, as well as the faithful, who are beckoned to and welcomed at our celebrations of the mystery of God’s coming among us as one of us.

In the young Diocese of Leeds (formed just under six years ago), we have three cathedrals. This is unique in England and we’re enjoying the challenge of working out how to work it out. At Christmas, I will cele-brate in each of them—Bradford, Wakefield and Ripon. Each has its own character, history and identity. Each has a history and a story worth telling. And each bears witness to the impact of the Christmas event on societies and individuals for more than a millennium. But why should we keep telling the Christmas story and celebrating the fulfilment of Advent hopes and expectations?

Well, let’s be honest: many of the faithful and faithless who will come to our cathedrals and churches around Christmas will be doing so in order to keep a family tradition going through to the next generation. And some will want to find some security in the midst of a scary, insecure or bewildering world.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Others will find themselves drawn by the aesthetics of candle-lit buildings that remind us of both human transience and value in a changing world. And others still will want to be surprised by hope, opened up to the possibility of meaning or grasped afresh in their imagination by a mystery that cannot be contained in mere words and concepts. All are welcome and any motive is fine by me.

'We had a teenager act out a monologue of Mary in labour wrestling with doubt and fear as her baby moved out of the warmth of the womb and towards the light of a conflicted world'

Once, when I was a vicar in Leicestershire, a group of us tried to work out how we could tell the Christmas story afresh so that it would be familiar, but surprising. In the end, we began in total darkness in the church that was more than 1,200 years old. Into the expectant silence came a voice saying simply: ‘In the beginning... In the beginning it was dark.’ The service then moved us in word and music through the story of God loving his creation, not being surprised by how mad and bad it had become, but how, entering into the heart of it, he changed everything for ever. We had a teenager act out a monologue of Mary in labour wrestling with doubt and fear as her baby moved out of the warmth of the womb and towards the light of a conflicted world. It was shocking and totally arresting.

I recall that story because one couple who attended felt deeply moved by the whole experience. A couple of days later, on Christmas Eve, the husband was hit by a vehicle and died on Christmas Day. What did the story told in the carol service have to say when a world has fallen apart and family joy is destroyed by loss and deep grief? This is not a question I’ve asked on only one occasion.

Living in Kendal, Cumbria, in 1988, I was sitting under the flight path of an aeroplane that exploded over Lockerbie on December 21. On Christmas Eve, I saw a young woman in the congregation who had dropped off two American friends at Heathrow before driving north to her family. Another young woman was changing trains in Lockerbie in order to visit Kendal for Christmas when the plane came down. Both were wrestling with their emotions and their imagination.

The thing is this: romantic nonsense about baubles and tinsel simply don’t cut it when your life has been torn apart and your expectations of the world have been demolished. Cleaned-up images of a baby in a sanitised manger in a well-swept stable block are meaningless – possibly even offensive – when they collide with reality and the world we know.

Just as well, then, that the original story is itself full of reality and grit. For this story is about God opting into the real world of pain and joy, fear and suffering, hope and longing. It describes in mere words the mystery of a love that declines to offer advice from a distance and gets down and dirty where we are.

'It tells of a unique event in history that raises questions for everyone about why the world is the way it is and how we can live differently within it—in the light of this baby of Bethlehem'

The baby of Bethlehem will one day watch his distraught mother watching him as his tortured body breathes its last on the gallows planted in the rubbish tip outside the walls of the city. No romantic illusions; no pretence; no playing religious games aimed at making us feel better.

So, this is the power of Christmas – for the faithful and for the faithless. What makes the difference is our openness to be surprised by the story told afresh. It’s a story to be questioned and argued with, wrestled with and pushed to its limits.

It’s a narrative that has shaped our history (see Tom Holland’s excellent new book Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind, published by Little, Brown) and become dulled by familiarity.

However, it tells of a unique event in history that raises questions for everyone about why the world is the way it is and how we can live differently within it—in the light of this baby of Bethlehem.

We are no more exempted from all that the world can throw at us than God himself. It’s this that encourages me to wish everyone – the faithful and the faithless – a happy and earthy Christmas.

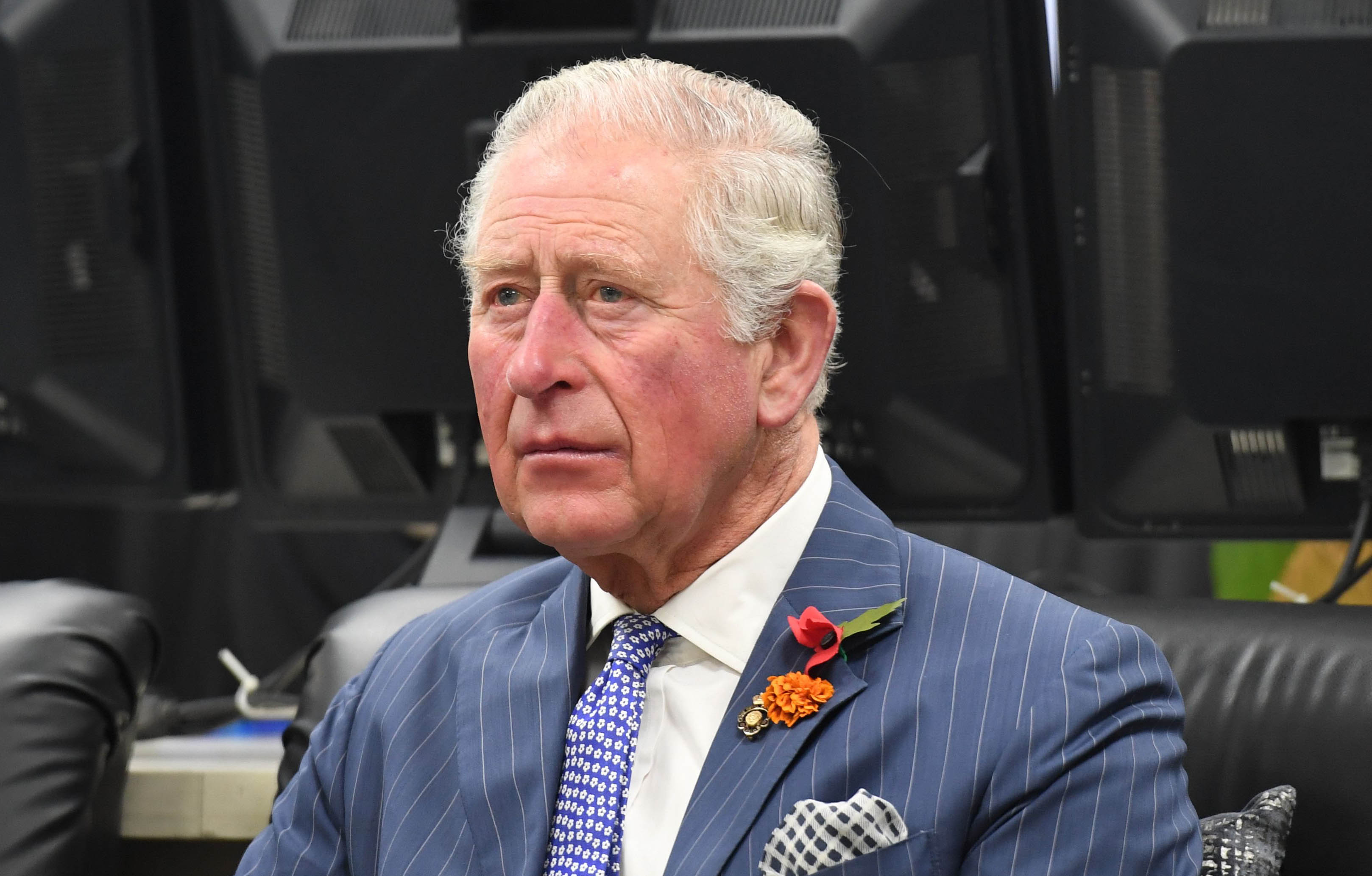

HRH The Prince of Wales: 'We urgently need a fresh, positive and practical vision for the countryside'

In his birthday message, The Prince of Wales applauds efforts to combat climate change and acknowledges the urgent need to

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.