Athena: It shouldn't take a blazing fire for us to see the value in our places of worship

If major catastrophes have any advantages, it is that, by shocking us, they can focus attention and resources.

When Notre Dame in Paris burned on April 15, 2019, the world looked on in bewildered horror. Now, after five years of intensive labour and the expenditure of €700 million, we rejoice to see the church resplendent and reopened.

From the images she has seen, Athena is struck to see how transformative the restoration has been. The interior — formerly so dark — looks dazzling, a change she suspects much in the spirit of the recently restored interiors of Chartres Cathedral or the Abbey of Fontevraud, the burial church of Henry II, Eleanor of Aquitaine and Richard I, also in France.

It’s hard to imagine such a finish winning approval in the UK. Whatever the case, Athena must admit that she didn’t believe that the project could be finished so quickly. There are still external works to complete, of course, but she stands corrected of her doubting and is deeply impressed by what has been achieved. It will be a treat to visit when next in Paris.

'It’s another cut, invisible to most, that promises to do gradual, but irreversible harm'

If major catastrophes have any advantages, it is that, by shocking us, they can focus attention and resources. In the case of Notre Dame, they also make us realise how we bestow exceptional value on some things that — until they prove themselves to be vulnerable — we take completely for granted. How much harder it is to focus on disasters that are incremental and take place more gradually over years. The slow pace anaesthetises us to the change, however horrifying it is.

Seeing the cathedral of Paris restored with such fanfare and at such vast cost makes Athena think of the UK’s historic parish churches. At the moment of going to press, the Chancellor has still not formally agreed to extend the Listed Places of Worship scheme that offers VAT relief for repairs to these buildings. It’s another cut, invisible to most, that promises to do gradual, but irreversible harm. The problem is that a leaking roof doesn’t provide the drama of a fire, but it can start a process of deterioration that is no less destructive and unaffordable to repair.

This year, we celebrate the 50th anniversary of ‘The Destruction of the Country House’, an exhibition at the V&A Museum that has been credited with turning the tide on the sale and destruction of these buildings. We now urgently need something to focus the public consciousness on the parish church. Christmas, when so many of us engage with these buildings, is a good moment to start.

The calamitous situation in Wales and Scotland should be a warning to us all that we can’t take these buildings anywhere for granted. The question of how they and their astonishing treasures are managed for the future is unquestionably squaring up to be the conservation battle of the moment. If the debate is to be initiated by an exhibition, then the Chancellor should be invited to open it. The experience might prick her conscience.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Athena is Country Life's Cultural Crusader. She writes a column every week.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

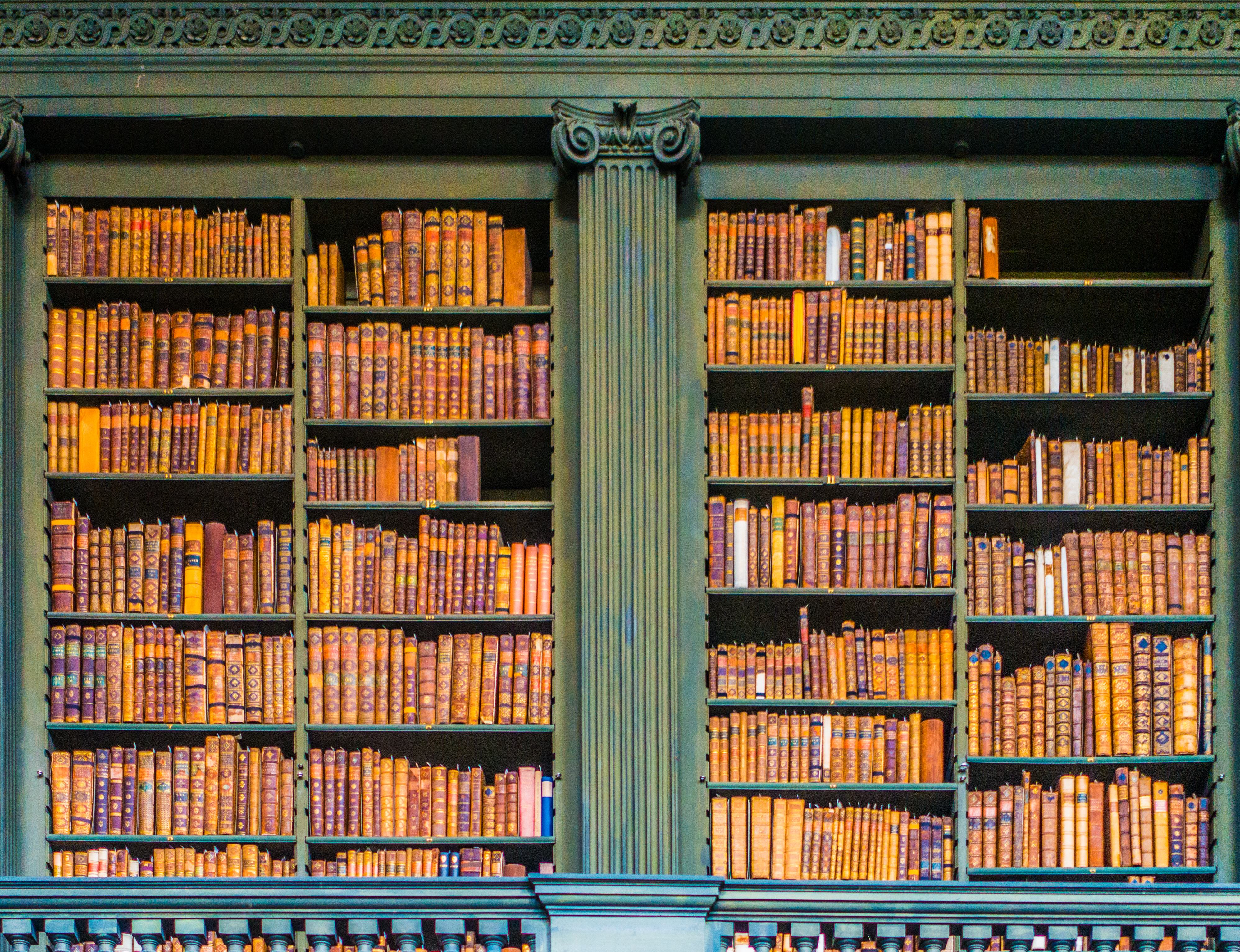

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life