Anglo-American marriages: The special relationships

Prince Harry is not the first Englishman to lose his heart to an American girl. Clive Aslet charts the long-standing tradition of transatlantic marriages.

We are not surprised: Prince Harry has lost his heart to an American girl.

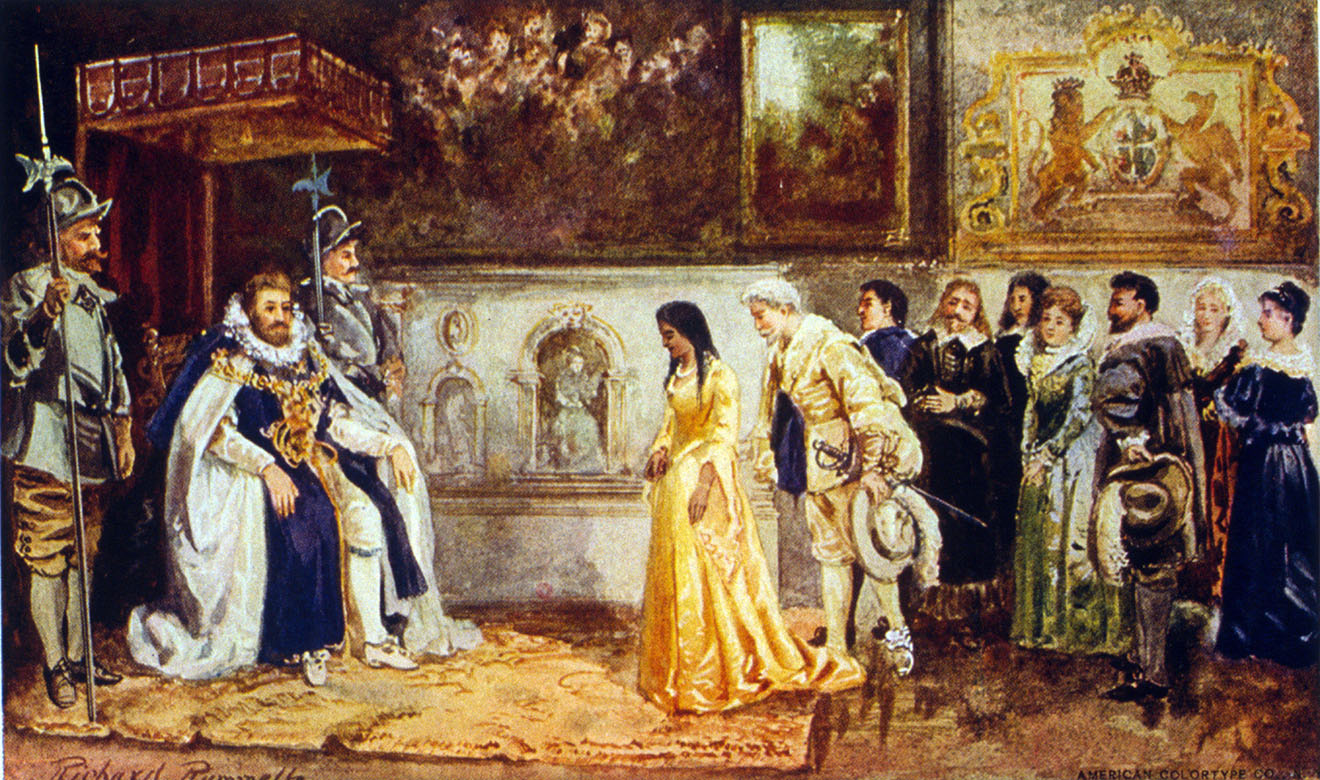

In doing so, he stands in a long tradition. It’s too much, perhaps, to recall Rebecca Rolfe, better known as the Native American Pocahontas, who married John Rolfe, a Virginian settler, and reached England in 1616.

However, she was scarcely less of a sensation than the young American women who exploded onto the British scene during the 1870s. Better educated than their English sisters, livelier and fearsomely well informed, they could converse on any number of subjects.

Concerned Society mothers may have cherished the thought that the British male found cleverness off-putting, but they were often proved wrong. In Henry James’s Daisy Miller, Count Otto could ‘immediately think of a dozen men he knew who had married American girls. There appeared now to be a constant danger of marrying the American girl… it was one of the complications of modern life’.

Edith Wharton called them the buccaneers – young women who braved the billows of the Atlantic in the hope of capturing a duke. This is not wholly fair to her compatriots as not all were heiresses and many didn’t marry titles. Several American beauties captivated the future Edward VII, with no hope of marrying him. Conversely, not all aristocrats were mercenary.

The model for the unhappy Conchita Closson in The Buccaneers was Consuelo Yznaga: born in New York City, her mother was the daughter of a steamboat captain, her father a Cuban diplomat. The impecunious 8th Duke of Manchester proposed to her after she and Mrs Yznaga nursed him back to health after a fever. They married in 1876 and he went bankrupt in 1890 – the fortune she acquired later probably came from her successful brother.

By 1914, as much as 17% of the aristocracy had American connections. Some brides found the social world of their new country bewildering and narrow, if not hostile.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Old Lord Scarsdale evidently had little idea how to charm his daughter-in-law, Mary Leiter from Chicago. ‘Do you have sea fish in America?’ he asked her, followed by: ‘I suppose you don’t know how to serve a good tea in America. We only know how to do it in England.’

But Scarsdale’s son, the famously aloof Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, adored his wife and she rose to occupy the highest position possible for a commoner: Vicereine of India. Alas, the subcontinent was too much for her and she died in 1906, soon after returning to England. Distraught with grief, he commissioned G. F. Bodley to add a memorial chapel to All Saints church Kedleston: two marble angels mourn over her. Curzon’s effigy lies next to hers – an arrangement that couldn’t have been tactful to his second wife, Grace, the Alabama-born widow of Alfredo Huberto Duggan of Buenos Aires.

‘How I should hate to be May Goelet,’ wrote Daisy, Princess of Pless, in her diary. ‘All those odious little Frenchmen, and dozens of others, crowding round her millions.’

Some were surprised at May’s choice, the 8th Duke of Roxburghe, known as Bumble, in 1903, but it was a devoted marriage. She redecorated Floors Castle as he played polo and shot.

May went into the marriage market with her eyes open. In 1895, she had been bridesmaid to Consuelo Vanderbilt at her marriage to the 9th Duke of Marlborough, known from his courtesy title (Earl of Sunderland), rather than temperament, as ‘Sunny’. Aged just 19, Consuelo had to preside over the family’s houses at the same time as battling Sunny’s female relations for precedence.

She found both Blenheim and her husband cold. In her memoir The Glitter and the Gold, she claimed that she had been bullied into the union by her mother – although this wasn’t obvious during the courtship in Newport, Rhode Island. Nor does the book mention how, having produced two male children, she fled to Paris with her married lover Charley Castlereagh, future Marquess of Londonderry, in 1905.

Some of the horrors of the marriage may have been overstated. Wanting to marry a French Catholic, she needed it to be annulled – Sunny, now a Catholic convert, acquiesced and married another American, Gladys Deacon. As his private papers have never been published, our knowledge of the Consuelo marriage is one-sided.

Sunny wasn’t the first Marlborough to take an American bride. His uncle, Lord Randolph Churchill, had married the spirited Jennie Jerome in 1874. ‘She shone for me like the evening star,’ wrote her son, Winston Churchill. ‘I loved her dearly – but at a distance’.

Through Jennie’s father, Leonard Jerome, a marriage prospect was spotted for Lord Randolph’s divorced elder brother, the 8th Duke. ‘I rather think he will marry the Hamersley,’ Lord Randolph Churchill reported to Jennie, ‘...there is no doubt that she has lots of tin.’ Friends unkindly rhymed Lilian Hamersley’s Christian name with ‘million’.

‘Heaps of the needful’ were a prerequisite for the young men on board Sir Thomas Fermor-Hesketh’s yacht as it sailed into San Francisco in 1876; he recorded as much in his diary. ‘Francis got hooked on’ to Miss Crocker, ‘very nice’ and also rich, ‘and has landed her I think. Hesketh has two on hand… Can’t make up his mind… I must say American girls are very pretty, dress well, have good feet, lots of fun & very sharp. Some have lots of money.’

Sir Thomas’s choice fell on Florence Sharon, daughter of Senator Sharon of the Bank of California – a disreputable figure, but then San Francisco was a long way from Easton Neston and Rufford Old Hall, where the dowry would be spent.

With landed incomes in decline and outshone by the plutocratic fortunes of South African Randlords, armaments manufacturers and bankers, rich American marriages transformed many country houses. When Lutyens built Middleton Park, Oxfordshire, for the second Lady Jersey, film star Virginia Cherrill, in the 1930s, he supplied 14 bathrooms, Lady Jersey’s own being onyx.

Henry James was appalled when his friend, the American actress Mary Anderson, came to Broadway in Worcestershire with her husband Antonio de Navarro. ‘You, if I may say so, have made yourselves martyrs to the picturesque,’ he wrote after a visit to Court Farm. ‘You will freeze, you will suffer from damp. I pity you, my dears.’

There was no need for pity after it was restored by A. N. Prentice. Wilfred Buckley lived in the USA before marrying heiress Bertha Terrell in 1899. When they came to Hampshire and built Moundsmere Manor, to the designs of Reginald Blomfield, a decade later, it was equipped with American-style bathrooms and closets and Buckley began a campaign for clean milk. Moundsmere milk was supplied to Buckingham Palace.

The supply of heiresses appears to have dried up in about 1910. By 1918, the relationship with American society had changed. Landed estates no longer radiated the same glamour; many were being broken up. Rather than looking down on the daughters of the New World, country-house owners envied the big houses outside New York City, Chicago and Philadelphia, some with indoor swimming pools, squash courts and bowling alleys, as well as polo grounds and gardens – in short, modern.

To the Prince of Wales, later Edward VIII, who visited the USA in 1919 and 1924, American life was refreshing after the fossilised rigidity of Court. He favoured vivid golfing attire, soft collars and cocktails; he began to affect an American accent, in preference to the previously fashionable faux cockney.

There were American girlfriends before Wallis Simpson and, when the prince acquired a weekend place, Fort Belvedere was remodelled like a house on Long Island.

Between the Wars, Americans in Britain could lead Society in a way that hadn’t happened in the Edwardian period. In London, Maud Cunard created one of the few salons where artists, writers, politicians and princes were to be found in the same room – perhaps it took an American’s lack of social inhibition to achieve it.

Her rival, Laura Corrigan, had married playboy James Corrigan, whose father owned a steel company; after his death in 1928, she began a determined assault on London Society, buying going-away presents of such value that few could resist her soirées.

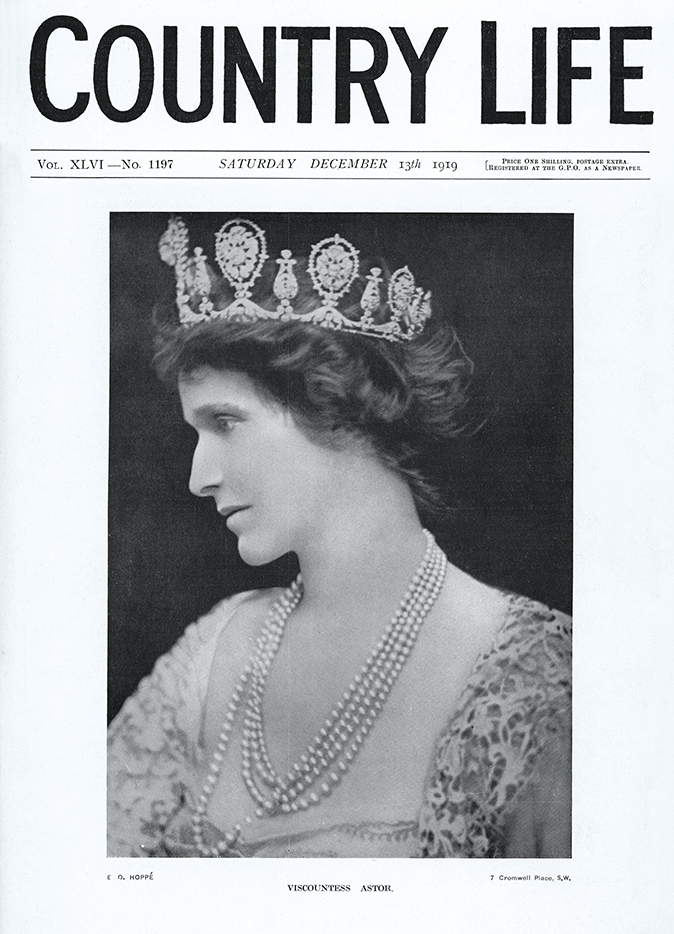

Two of the most prominent political sets of the period had American connections. The first was Cliveden, bought by the 1st Viscount Astor, an American, in 1906 and given as a wedding present to his son, who married Nancy Langhorne from Virginia, the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons. The second was Leeds Castle, where the chatelaine, Lady Baillie, was the daughter of socialite Pauline Whitney.

Meanwhile, Nancy Astor’s Virginian niece, Nancy Lancaster, was becoming the acknowledged queen of the decoration of country houses. It may be that her American eye was quicker to see that a simpler way of life did not have to mean a less elegant one.

Decoration is evanescent, but happily her own house of Ditchley was recorded in watercolours by Alexandre Serebriakoff in the 1940s; these show the balance, refinement and ease that she brought to homes after the Second World War, in what for decades was thought of as the English country-house look.

One of the most evocative images of the 1930s Georgian Revival ideal is Rex Whistler’s painting of Mr and Mrs Robert Tritton, sitting beneath a tree in front of Godmersham Park, Kent, as a butler crosses the lawn with a tea tray. Elsie Tritton was an American whose deceased first husband, Sir Louis Baron, had owned the company that made Black Cat cigarettes.

To turn Godmersham into a place of Jane Austen-like elegance (the house had been owned by Austen’s brother, Edward Knight), the Trittons employed American architect Ogden Codman, co-author of The Decoration of Houses with Edith Wharton, to remodel it. Whistler’s painting, therefore, commemorates a triumph of Anglo-American taste.

The Edwardian ocean liner, which could itself foster romance, has now been replaced by the Boeing and Airbus. Distance has been eliminated and the American girl is more familiar than she was a century and a half ago, but no less delightful. Or so Prince Harry has found – and the rest of the nation is sharing the love.

Clive Aslet is author of ‘An Exuberant Catalogue of Dreams: the Americans who Revived the Country House in Britain’

HRH Prince Harry – a profile: An exceptional young man in an exceptional situation

Fun loving, but fiercely protective of Meghan Markle, Prince Harry thrived in the army and, with her support, will continue

Credit: Prince Harry - PA

Prince Harry: 'Even if I were King, I'd do my own shopping'

HRH Prince Harry has given a fascinating interview in which he has spoken in-depth about his life, his mother, and

Credit: Prince Harry and Meghan Markle

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle: The happy couple pose for first official photographs

Prince Harry and his actress fiancée Meghan Markle posed for a series of photographs in the Sunken Garden at Kensington