Tina – the Musical review: A recreation of Tina Turner so good that the star's name 'should be set down in pillars of lasting fire'

Michael BIllington went to see Tina, the new musical about the life of the singer, and was staggered by the energy of Adrienne Warren in the lead role – and he compares it to a very different experience at David Hare's play about Glyndebourne.

Tina - The Musical

By Katori Hall – Aldwych Theatre, booking until February 2019

With Tina, at the Aldwych Theatre, we enter the world of the soul and rock singer Tina Turner, and of her triumph over adversities that included troubled parents, an abusive husband and the initial scepticism of the record industry about the likely success of a 40-year-old woman of colour.

Miss Turner, who I was intrigued to discover is only 10 days younger than myself, not only survived, but went on to sell millions of records and eventually achieve marital happiness. It’s a classic rags-to-riches showbiz story and is recounted with loving devotion by Katori Hall in a manner that, unsurprisingly, has been given its subject’s imprimatur.

There’s one outstanding reason for seeing this show: Adrienne Warren. She doesn’t so much mimic Miss Turner as vividly re-create her, displaying a voice that easily encompasses songs such as River Deep, Mountain High and using her piston legs to astonishing effect. I believe it was Blake who said that energy is eternal delight and Miss Warren has more energy than I’ve seen for years in any performer: she could have danced all night.

There’s good work from Kobna Holdbrook-Smith as the exploitative Ike Turner, pleasing designs from Mark Thompson and a bustling production from Phyllida Lloyd, but it’s Miss Warren whose name should be set down in pillars of lasting fire.

The Modern Soprano

By David Hare – Duke of York Theatre, until June 19

You wouldn’t expect a play about Glyndebourne from David Hare – he’s usually associated with scathing critiques of contemporary society – but, in The Moderate Soprano, now at the Duke of York’s, he’s written a beautiful, touching play that not only explores the foundation of the Sussex opera house in 1934, but also provides that rarest of things in modern theatre: a celebration of married love.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

His basic point is that a quintessentially English institution owes its initial success to European emigré talent. It was John Christie, a former Eton schoolmaster and benign eccentric, who had the vision to create an opera house in rural East Sussex: it was his wife, the soprano Audrey Mildmay, who had the practical wisdom to realise her husband’s dream.

However, the play leaves you in no doubt that Glyndebourne’s pre-war reputation rested on three refugees from Hitler’s Germany: conductor Fritz Busch, director Carl Ebert and intendant Rudolf Bing, later a pillar of the Edinburgh Festival and the Metropolitan Opera.

Sir David makes much sport out of the initial conflicts between Christie, who wanted to christen the house with Parsifal, and the imported triumvirate that saw that Mozart was the ideal composer for an intimate jewel-box of a theatre.

There are times in the first half when you feel a good deal of information is being offloaded, but the play comes into its own in two unexpected ways. Christie delivers a rhapsodic speech in which he dismisses the practical hazards of getting to Glyndebourne by suggesting that opera offers a glimpse of the sublime: a ringing defence of great art that’s as inspiring as it is unfashionable.

There’s an equally unexpected tribute to the power of conjugal love: admittedly, we see Audrey in the post-war years when she’s a sick woman, but there’s something deeply moving about Christie’s attempt to console her by reciting a list of the great Mozart productions. If Sir David’s contemporary, Howard Brenton, hadn’t already used the title, the play could well be called Christie in Love.

A lot of the pleasure lies in the quality of the performance. There are few better actors in Britain than Roger Allam, who captures perfectly Christie’s mix of bull-headed dogmatism, belief in the power of art and plain uxoriousness. Nancy Carroll vividly conveys the tension between Audrey’s role as gracious country-house hostess and rightly ambitious artist. There’s strong support from Paul Jesson as the burning Busch, Anthony Calf as the implacable Ebert and Jacob Fortune-Lloyd as the diplomatic Bing.

Bob Crowley’s sets, especially when they take you into the garden, remind me of a comment by a friend on visiting Glyndebourne on a perfect summer night: that this must be as close to heaven on earth as one can get.

The Billies: Country Life's 2017 theatre awards, from best play to Ayckbourn's 'crushing disappointment'

After watching new productions at a rate of about four a week, our theatre critic Michael Billington presents the brilliantly

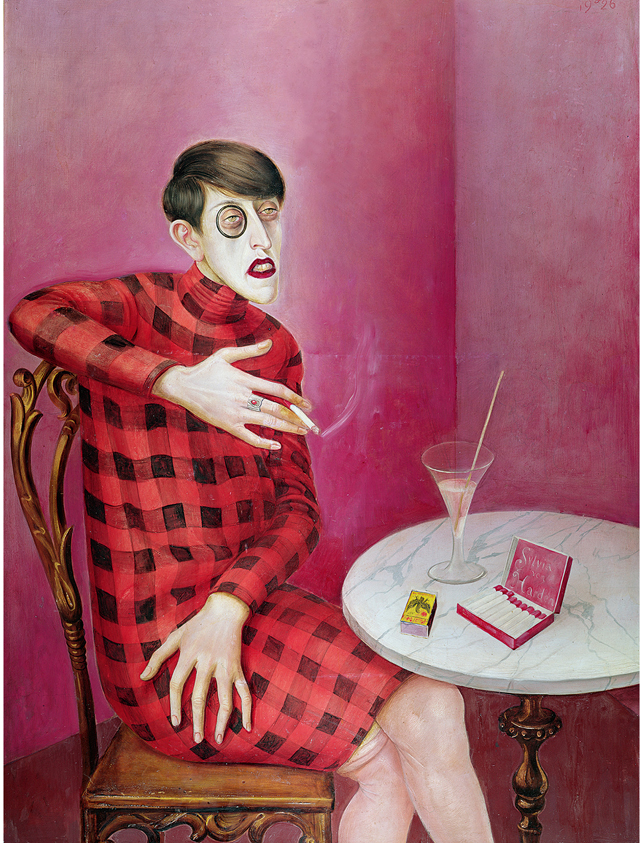

My favourite painting: Michael Billington

Michael Billington chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Living La Dolce Vita: Skye McAlpine's Italian-inspired pop-up opens in Belgravia

Living La Dolce Vita: Skye McAlpine's Italian-inspired pop-up opens in BelgraviaHer new tableware shopping experience in central London showcases the writer and founder of Tavola's love of Venice.

-

A 10-bedroom manor house in the heart of the Cotswolds with all the trimmings

A 10-bedroom manor house in the heart of the Cotswolds with all the trimmingsWaterton House sits on the edge of Ampney Crucis, and is as elegant as can be.