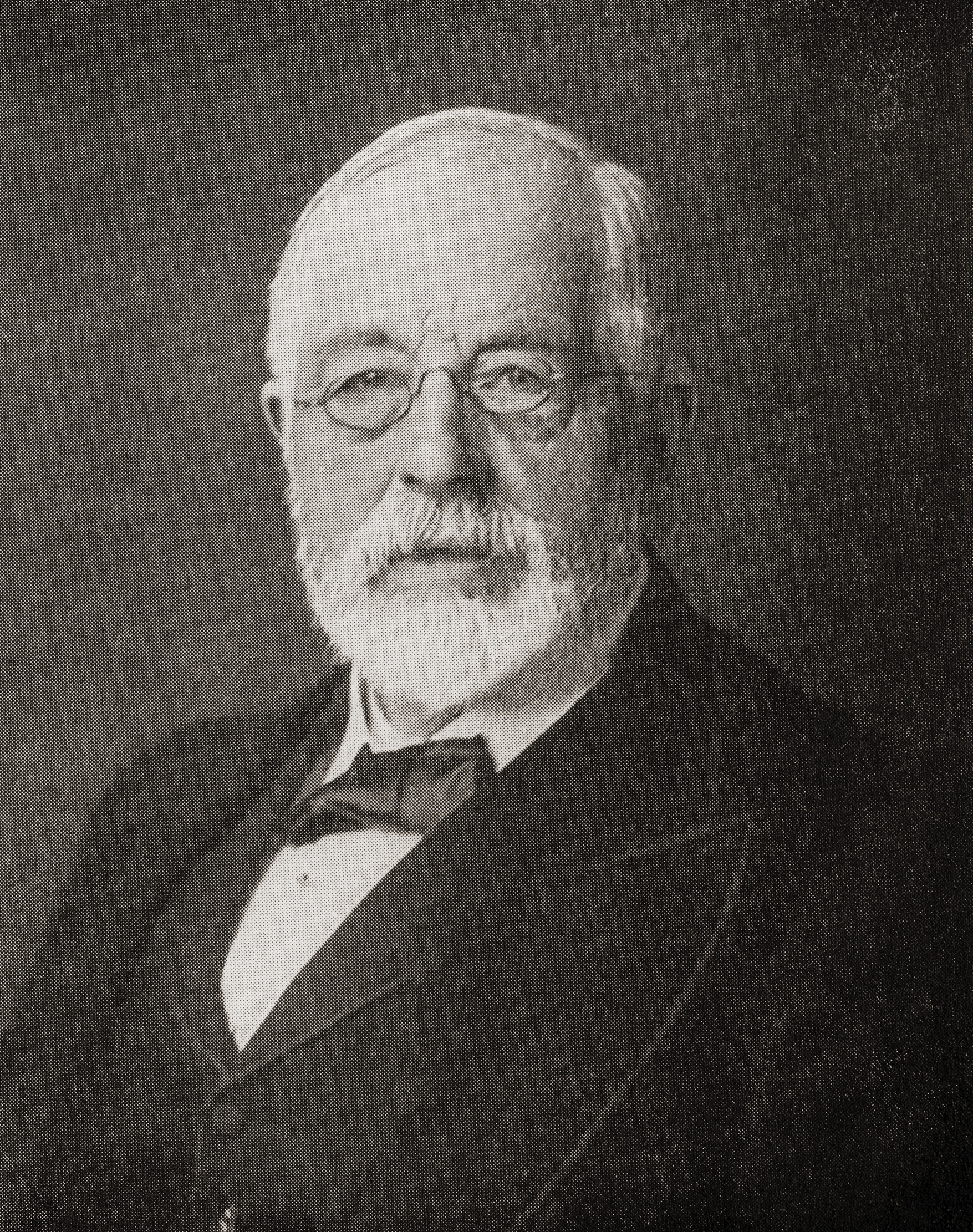

The Legacy: Sir Henry Tate and art for all

After making his fortune in the sugar business, Sir Henry felt he deserved to give something back to the nation. And so, the Tate gallery was born.

When Henry Tate, the 11th child of a Lancashire Unitarian minister, had success as a grocer, he branched out into the sugar business (by then less tainted by slavery, which had been abolished in 1833–34).

He introduced better refining techniques and embraced European methods to lump sugar into small cubes. Having made a fortune, Tate (1819–99) could have wielded much influence, but he had little interest in office and even less in fame; he donated generously, but quietly. He did, however, have one great passion: art.

Tate supported contemporary British artists — he was a personal friend of John Everett Millais — and his collection soon included some of the best paintings of the time, such as Millais’s Ophelia and John William Waterhouse’s Lady of Shalott (top).

All this Tate intended to leave as a bequest to the nation, but the National Gallery, which lacked space, turned it down. This prompted him to fund a new British-art museum, ‘as a thank-you offering for a prosperous career of sixty years’.

The notoriously modest Tate was offered a baronetcy twice and twice he declined it. The third time, the Marquess of Salisbury made a point of telling him that one more refusal would amount to an insult to Queen Victoria — so Tate duly accepted

When the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) opened it on July 21, 1897, Tate — a man who usually avoided public speaking at all costs — had words of praise for everyone else, from the curators (Sir William Agnew and Sir Edward Poynter) to the architect (Sidney Smith) and even the building contractors (Higgs and Hill), as well as the Prince: ‘Today, your Royal Highness puts the crown on the undertaking by graciously opening this gallery… and I venture to hope that the event… may be taken as a happy augury of its success.’

With that, the National Gallery of British Art was born — except it never really went by that name, becoming known as Tate Gallery.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Credit: Tony Evans/Timelapse Library/Getty Images

The Legacy: Miriam Rothschild, the pioneer of organic and wildflower gardening

The celebrated entomologist and Bletchley Park codebreaker was also way ahead of the times when it came to gardening.

Credit: R A Kearton via Getty Images

The Legacy: Godfred Baseley, the man who invented The Archers

We take a brief look at the life and inspiration of the man behind the world's longest running radio serial.

Credit: Ralf Hettler/grafissimo via Getty Images

The Legacy: Thomas Twining, the man who made such good tea, not even the Boston rebels would toss it in the harbour

Arriving in London as a young boy, Thomas Twining saw a gap in the market, and made his name as

The Legacy: David Austin's English roses

Tiffany Daneff pays tribute to David Austin, the man whose name remains synonymous with roses even five years after his

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.