Put new art into old houses

Jeremy Musson looks at the skill of placing contemporary art into historic houses

Collecting and commissioning art for the country house has been a feature of English aristocratic life since the 17th century. Paintings were acquired for reasons of dynastic pride-especially portraits-and as an exercise in taste and patronage. Tastes change and the collections of country houses have often adapted to reflect the different priorities of different ages, one generation commissioning works from living artists, the next collecting Old Masters, as we see in so many collections.

Garden temples might be filled with antique sculptures acquired on a Grand Tour or with pieces newly commissioned in the Classical spirit.

The pleasure of the encounter with artists themselves, having a portrait painted in the studio of Batoni in Rome or taking a glass of wine with the sculptor Canova, as the 6th Duke of Devonshire must have done, is not to be underestimated. Connoisseur-ship was a sign of refinement and country-house owners were not a little competitive in the building up of their collections and often also saw it as a matter of national pride that the collections of the English country house should rival those of the princely houses of Europe.

The story has never been entirely static and, in the 21st century, as more historic houses are opened to the public, the commissioning and acquisition of adventurous contemporary art for their interiors and landscapes has never been so lively, reflecting a long tradition of sheer personal enjoyment.*

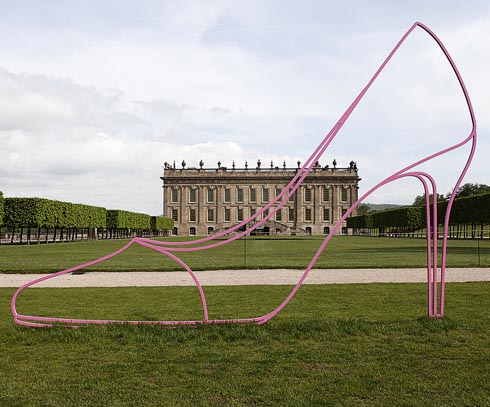

The Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth, Derbyshire

The Devonshires have led the field in commissioning and showing contemporary art in the historic country house. The newest addition, unveiled late last year, is a ceramic room installation in the North Sketch Gallery by Jacob van der Beugel that involves portrayals of the DNA of the Duke and Duchess and their heirs, using textured, handmade ceramic panels (page 114). ‘This is a permanent addition and not a transitory one: an extraordinary layered work of art,' explains the Duke.

The Duke developed his interest in art when working for Sotheby's for two decades (he is a former chairman)-‘I have been very lucky to see so much that I wouldn't have seen otherwise in private collections'-and he has had a personal passion for contemporary art since the 1960s. ‘I especially enjoyed exhibitions at the Kasmin gallery then and my wife Amanda's family were keen collectors of modern art. My father commissioned portraits by Freud-many of my parents' friends hated his portrait of my mother, but I think I learnt from the experience that it doesn't matter what other people think if you believe it's worth doing.'

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Duke feels a conscious drive to bring new and interesting things to Chatsworth: ‘We all enjoy the way contemporary artists, such as Michael Craig-Martin and Edmund de Waal, respond to the historic collection, for instance, the latter being inspired by Delft blue-and-white ceramics.' Sculp- ture in the garden is another major feature at Chatsworth and the outdoor exhibition ‘Beyond Limits' is now an annual event (this year on September 8-October 26). ‘We have had a Richard Long piece, which is really beautiful, as a permanent addition and pieces by Elisabeth Frink acquired by my parents and then us; we have also added a site-specific work by David Nash.'

‘Michael Craig-Martin at Chatsworth', a major display of contemporary sculpture in the garden, runs until June 29 (01246 565300; www.chatsworth.org)

Hannah Rothschild at Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire

In the 19th century, the Rothschilds made Waddesdon Manor a temple to the Arts. The house was vested in the National Trust in the mid 20th century, but the family remains closely involved and supports the collection through a family trust.

Hannah Rothschild looks at the challenge of bringing contemporary art to her family home with relish: ‘What is really interesting about Waddesdon is that it's always reflected the taste and manias of the family at any one time. The house and collection are eclectic and touched with different personalities. When Ferdinand [de Rothschild, 1839-98] brought his art together, he was looking back-at the French and British 18th century. They were a tight-knit, Europe-wide family who influenced and competed with each other. James de Rothschild was the first to commission contemporary work, getting Bakst to paint the "Sleeping Beauty" series from 1913.'

Hannah adds that her father, Jacob, ‘has been very influential in choosing contemporary pieces. His taste is idiosyncratic-he's bought a Chardin for the collection and works by Edmund de Waal, all of which can sit quite happily together. The Ingo Maurer "shattered" porcelain chandelier, introduced in 2004, is a good example of something commissioned with a Waddesdon interior in mind-and it refers to the great Sèvres collection'.

The most dramatic pieces are to be found outside: ‘We have a perfectly formed time capsule in the collection and we don't want to play with that too much or dilute it, but, outside, we can be more adventurous. Sarah Lucas has recently done an extraordinary scaled-up model of a china horse, It might be called Perceval, which has a deliberate link to the landscape and agriculture. We have other pieces by Richard Long, Stephen Cox and Angus Fairhurst. In the family rooms, we do have contemporary works, including portraits by Lucian Freud and David Hockney.' (01296 653226; www.waddesdon.org.uk)

Mollie Dent-Brocklehurst at Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire

Mollie is a leading London gallerist and president of Pace Gallery on Burlington Gardens, W1. ‘I started to work in the contemporary art world almost as soon as I left college,' she says. ‘After setting up Gagosian in London in 2000, and seeing the exciting London art scene of the period, I began to be interested in linking the two parts of my life. I had seen some interesting sculpture parks in Europe, such as Villa Manin in Italy, and realised there was nothing like that in England.

‘We invited artists to respond to the architecture and the 1,000 years of history of the site: Carsten Höller made an extraordinary carousel, Wim Delvoye a dump truck using Gothic architecture, Jane and Louise Wilson introduced a sound-piece of church bells in the yew hedges and Jim Landby created "keyholes" in the garden.

‘Last year, with the Pace Gallery, we had spectacular outdoor works by Alexander Calder. We also recently installed Hiroshi Sugimoto portraits of Henry VIII and his six wives in the chapel to celebrate the 500-year anniversary of Katherine Parr.'

These are temporary exhibitions, but Vito Acconci's Face of the earth has remained a permanent piece at Sudeley. Mollie works closely with Elliot McDonald, both at Sudeley and at Pace London. This summer, she's involved in a project in Switzerland, where ‘we've been invited to "inhabit" an ancient medieval house with an underground gallery-this is an exciting way to explore the art'.

At Sudeley Castle, she feels that external spaces have been the right place for new shows and installations. After all, she says, ‘the landscape of a country estate is, in some ways, a living sculpture in its own right'.

(01242 602308; www.sudeleycastle.co.uk)

The Marquess of Cholmondeley at Houghton Hall, Norfolk

In 2013, David Cholmondeley hosted a major exhibition in collaboration with the Hermitage in St Petersburg, bringing back to Houghton the collection sold from the house in the late 18th century. However, he also has a serious commitment to the new, driven, he says, by ‘an interest in the artists and their response to the landscape at Houghton'. His own ideas about contemporary art have developed ‘through travel and through seeing things in other collections and other places'.

He has always had an especially strong interest in the history of Houghton's landscape and, inspired by the temples and gazebos in old plans of the 1720s, he commissioned James Turrell's Skyspace and Richard Long's slate Full Moon Circle ‘as modern responses to that same tradition-a way of adding interest to the experience of the garden and park. I felt they should be away from the house so they didn't interrupt the enjoyment of the historic architecture and I wanted to give each piece its own space-its own world'.

Mr Turrell chose a space and worked with an architect to realise a structure, which is approached up a ramp and is a little like a treehouse in feel. David adds: ‘The aperture to the sky creates an interior light best seen at dusk-it's all about perception.'

He relishes working with living artists just as his ancestor Sir Robert Walpole enjoyed working with William Kent in the 18th century: ‘Rachel Whiteread has recently created a "negative space" piece in the wood based on a derelict gamekeeper or shepherd's hut.' It's one of several projects contributing to a small but significant collection appropriate to a place like Houghton.

(01485 528569; www.houghton.com)

* Follow Country Life magazine on Twitter

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Alan Titchmarsh: 'It’s all too easy to become swamped by the ‘to-do’ list, but give yourself a little time to savour the moment'

Alan Titchmarsh: 'It’s all too easy to become swamped by the ‘to-do’ list, but give yourself a little time to savour the moment'Easter is a turning point in the calendar, says Alan Titchmarsh, a 'clarion call' to 'get out there and sow and plant'.

By Alan Titchmarsh

-

Rodel House: The Georgian marvel in the heart of the Outer Hebrides

Rodel House: The Georgian marvel in the heart of the Outer HebridesAn improving landlord in the Outer Hebrides created a remote Georgian house that has just undergone a stylish, but unpretentious remodelling, as Mary Miers reports. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

By Mary Miers