My favourite painting: Matthew Girling

Matthew Girling chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Jewelled locket with a portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, about 1600, by Nicholas Hilliard (1542– 1619), 21⁄2in by 2in, V&A, London

Matthew Girling says: ‘This ethereal image of Elizabeth is one of Hilliard’s most enigmatic. But, for me, it’s the depiction of the jewels, rubies and pearls that I find mesmerising. Jewels have always been in my family—my ne’er-do-well grandfather mined sapphires in Australia, only to gamble away the fortune he made. His one legacy was a passion for stones, and I have spent my life working with them. After prospecting for diamonds and working at Garrard, I belatedly went to university and this miniature—iconic in the literal sense—was the subject of my thesis. You could say the picture made me who I am today.'

Matthew Girling is Joint Group CEO of Bonhams and head of jewellery. The Fine Jewellery Sale is at Bonhams New Bond Street, London W1, on April 22

John McEwen comments: Shakespeare (1564–1616) and Hilliard lived into the Jacobean age, but embody the Elizabethan spirit, described by Sir Roy Strong, with regard to Hilliard’s art, as ‘utter freshness of vision’. Hilliard was the first English painter acknowledged as a supreme master by his English contemporaries. John Donne wrote in The Storm, ‘a hand or eye/ By Hilliard drawne, is worth a history,/ By a worse painter made’.

Hilliard’s father was an Exeter goldsmith and the city’s sheriff. The family were fervent Protestants. In Catholic Queen Mary’s reign, Nicholas—along with his protector, the exiled Exonian John Bodley (father of Thomas Bodley, founder of the Bodleian Library), and family—was received into John Knox’s Geneva congregation.

After Elizabeth I’s accession, he served a seven-year apprenticeship to Robert Brandon, the Queen’s goldsmith and jeweller. By 1572, he was her limner (miniaturist), an art derived from medieval book illumination, and had his own goldsmith workshop.

In his Art of Limning, Hilliard emphasised its respectability—‘fittest for gentlemen’. Often worn as jewellery, miniatures could be as expensive as full-length portraits. Hilliard was, nonetheless, invariably short of money and Brandon, now his father-in-law, had his daughter’s dowry separately managed.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This portrait was made when Elizabeth was about 66. Rubies and pearls boast her wealth; her crown, imperially closed, proclaims her subject to no worldly power. She is inviolate and ageless. Hilliard was jealous of the secrets of his surprisingly, when enlarged, impressionistic technique. His ‘cunning’ can defy any magnification, but we do know he burnished gold with a weasel’s tooth.

This article was originally published in Country Life, April 15, 2015

More from the My Favourite Painting Series

My favourite painting: Rose Paterson

Rose Paterson chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

My favourite painting: Neil MacGregor

Neil MacGregor chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

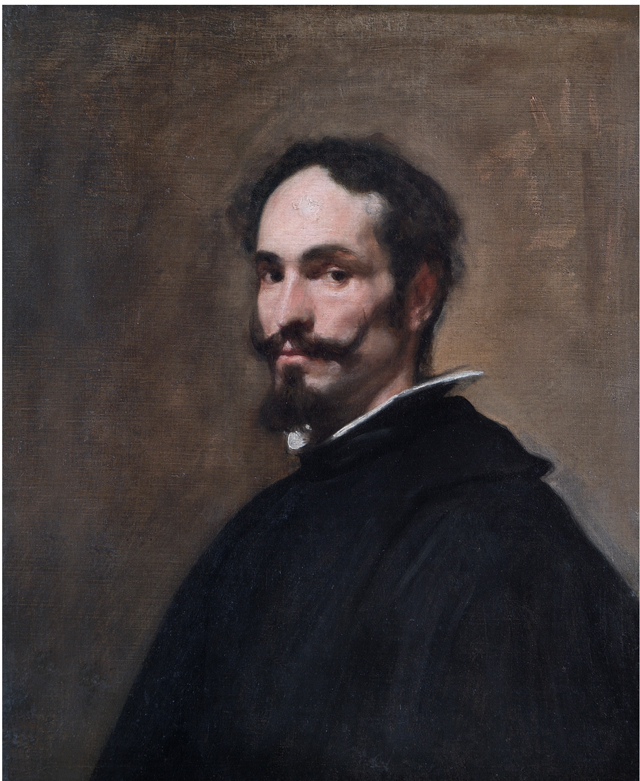

My favourite painting: Allan Mallinson

My favourite painting: Allan MallinsonMilitary historian Allan Mallinson picks an image of 'faith, generosity and ultimate sacrifice'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

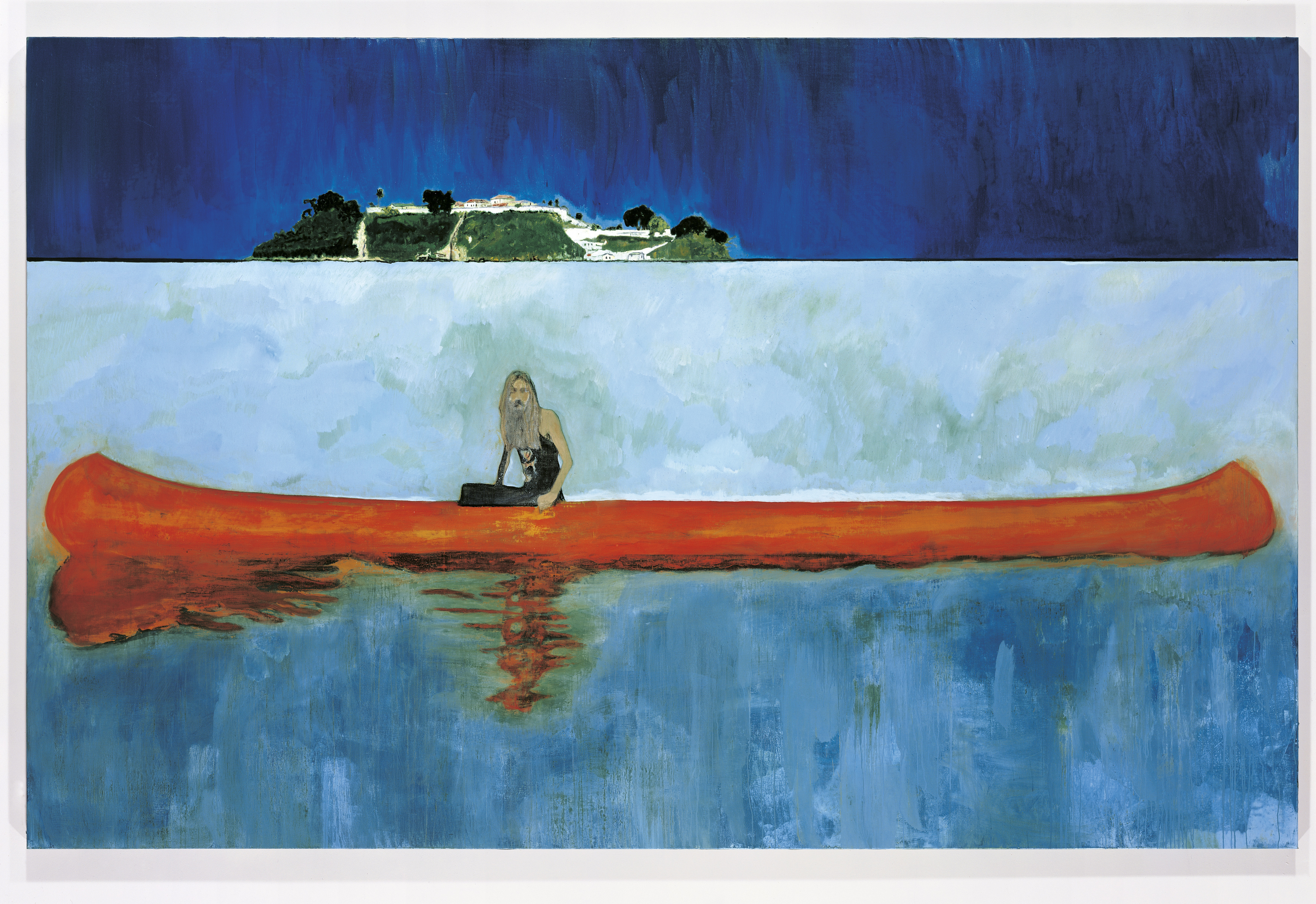

My Favourite Painting: Piet Oudolf

My Favourite Painting: Piet Oudolf'One cannot sense whether he is far out on the ocean or closer to shore, or what he may be watching or feeling in that moment as he stares towards the beach.’

By Country Life

-

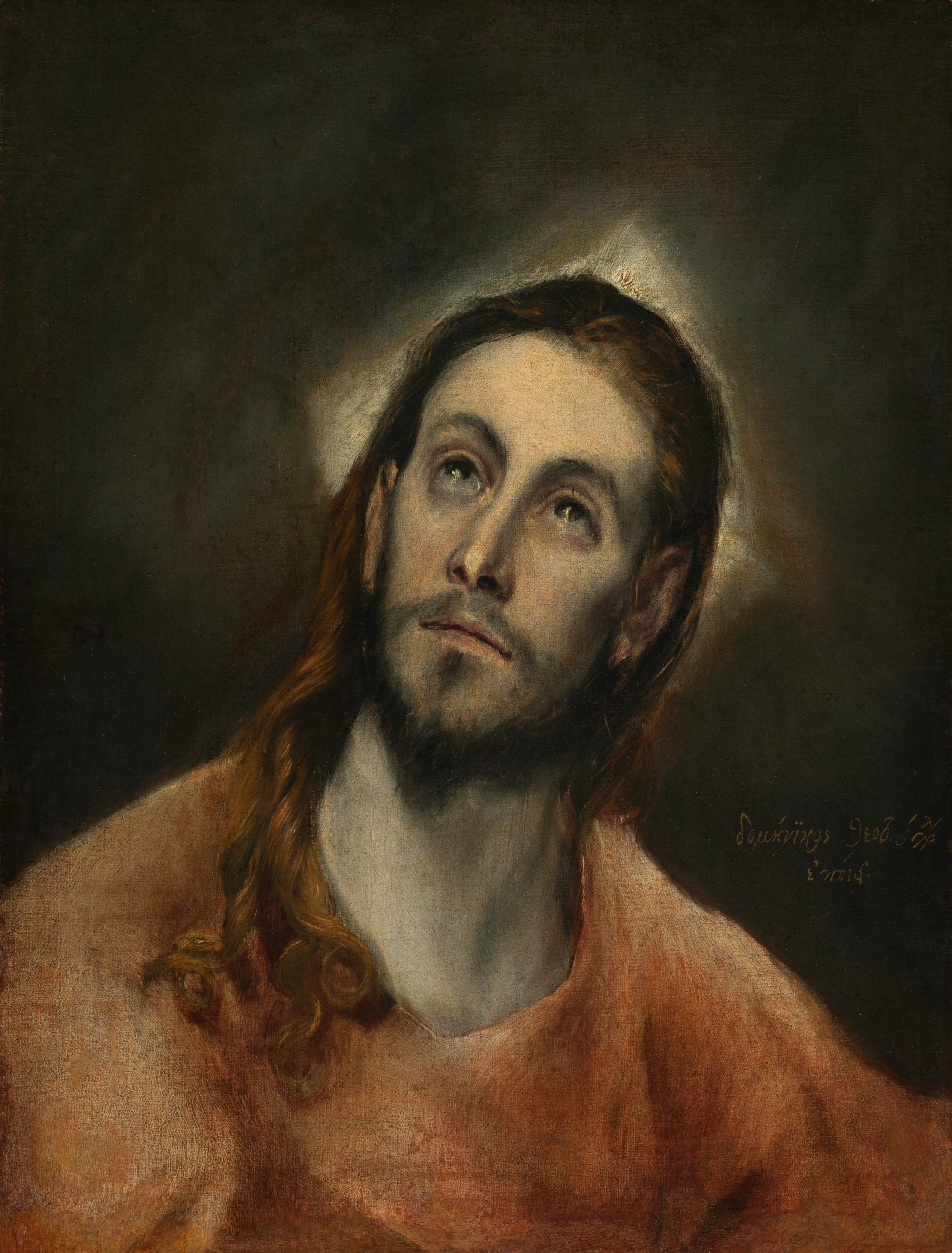

My Favourite Painting: Mary Plazas

My Favourite Painting: Mary Plazas'There is compassion, awe, humility, a knowing yet a questioning in the glistening eyes. It moves me, it inspires me beyond the need to know.’

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Robert Kime

My favourite painting: Robert KimeRobert Kime shares his fondness for New Year Snow by Ravilious

By Country Life

-

My Favourite Painting: Anna Pavord

My Favourite Painting: Anna PavordAnna Pavord chooses a picture which reminds her of where she grew up

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: The Duchess of Wellington

My favourite painting: The Duchess of WellingtonThe Duchess of Wellington chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Maureen Lipman

My favourite painting: Maureen LipmanMaureen Lipman chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Jacqueline Wilson

My favourite painting: Jacqueline Wilson'I looked at this painting and decided to write about a Victorian circus girl one day'

By Country Life