In Focus: The extraordinary William Morris, the man for whom the word polymath was coined

Famous for urging us to have nothing in our homes that is not useful or beautiful, William Morris’s masterful command of pattern and Arts-and-Crafts design masked a deeply unhappy marriage, says Michael Montagu.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

William Morris championed such an extraordinarily diverse range of Arts and interests that making an exact classification of him is difficult to achieve. A poet, romance writer, critic, socialist reformer, scholar and, above all, a prolific designer, he was a man for whom the word polymath was coined.

Born in Walthamstow on March 24, 1834, he was the third child and eldest son of a highly successful city broker. The family enjoyed a privileged lifestyle, settling at the Woodford Hall estate in Essex.

By all accounts, Morris was an indulged child, who is said to have enjoyed wearing a miniature copy of a medieval suit of armour when riding his Shetland pony in Epping Forest.

At the age of eight, his father took him to Canterbury Cathedral, an experience that he later described as feeling as if the gates of Heaven had opened for him. The memory of this first visit certainly seems to have remained in his mind, as, when he became involved with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), which he called the ‘anti scrapes’, his first project was the restoration of Canterbury’s choir.

Young William spent his time visiting churches and forests and enthusiastically reading the novels of Sir Walter Scott, all childhood pursuits that surely helped in the development of his love of Nature and historical romance. Indeed, his ideas pertaining to design were firmly established by the time he was 16.

During a visit to London in 1851, Morris refused to go to the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace, because its emphasis on mass-produced goods was contrary to his belief in traditional craftsmanship.

When Morris Snr died suddenly in 1847, leaving the substantial sum of £200,000 — mostly earned from his investment in a Devonshire mining operation — his son was assured a more than comfortable private income, giving him financial independence and obviating the need to earn his living.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

After attending Marlborough College, Morris went to Oxford’s Exeter College in 1852, where he read Classics, with the intention of taking Holy Orders.

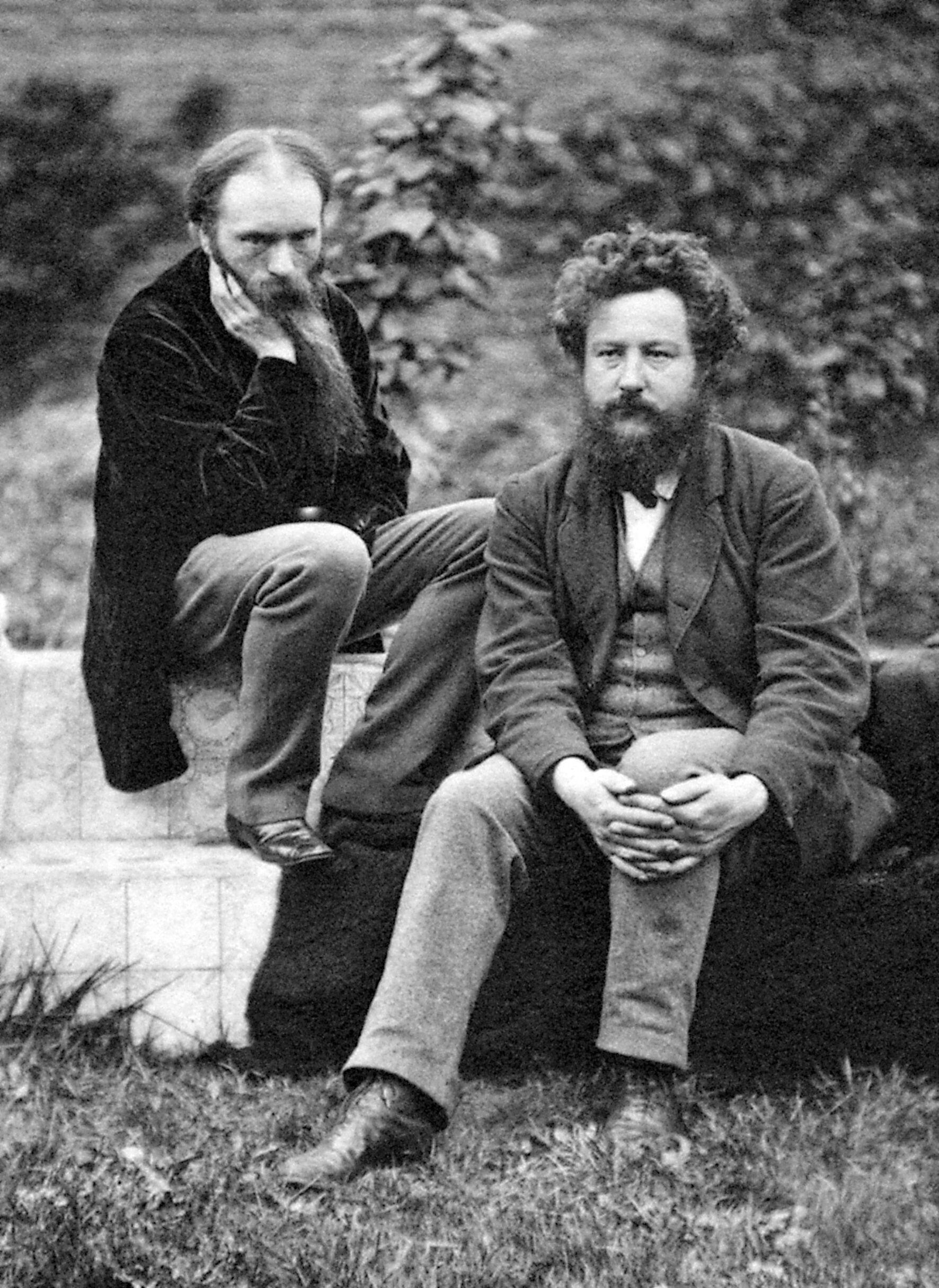

After an exam, he met Edward Burne-Jones, later destined for fame as a pre-Raphaelite painter, but then, like Morris, destined for the church. The two developed a lifelong friendship.

At Oxford, on his 21st birthday, Morris came into an annuity of £900, allowing him to finance a monthly student review, The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine.

The area around Oxford also inspired some of his later floral designs, not least the abundant snake’s-head fritillary in the fields at Iffley and wild tulips at Cherwell. After Oxford, Morris and Burne-Jones moved to London in the summer of 1856, sharing rooms in Bloomsbury.

None of the furniture then available suited their aesthetics, so they designed their own, which eventually led to the establishment of ‘The Firm’ in October 1861. During this time in London, they became part of a circle of artistic friends that included John Ruskin, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Robert Browning and Ford Madox Brown.

Although Morris had been articled to the Gothic Revival architect George Edmund Street, he was unsuited to the routine of office work and resigned after only a few months, giving himself the freedom to pursue a life of artistic endeavour.

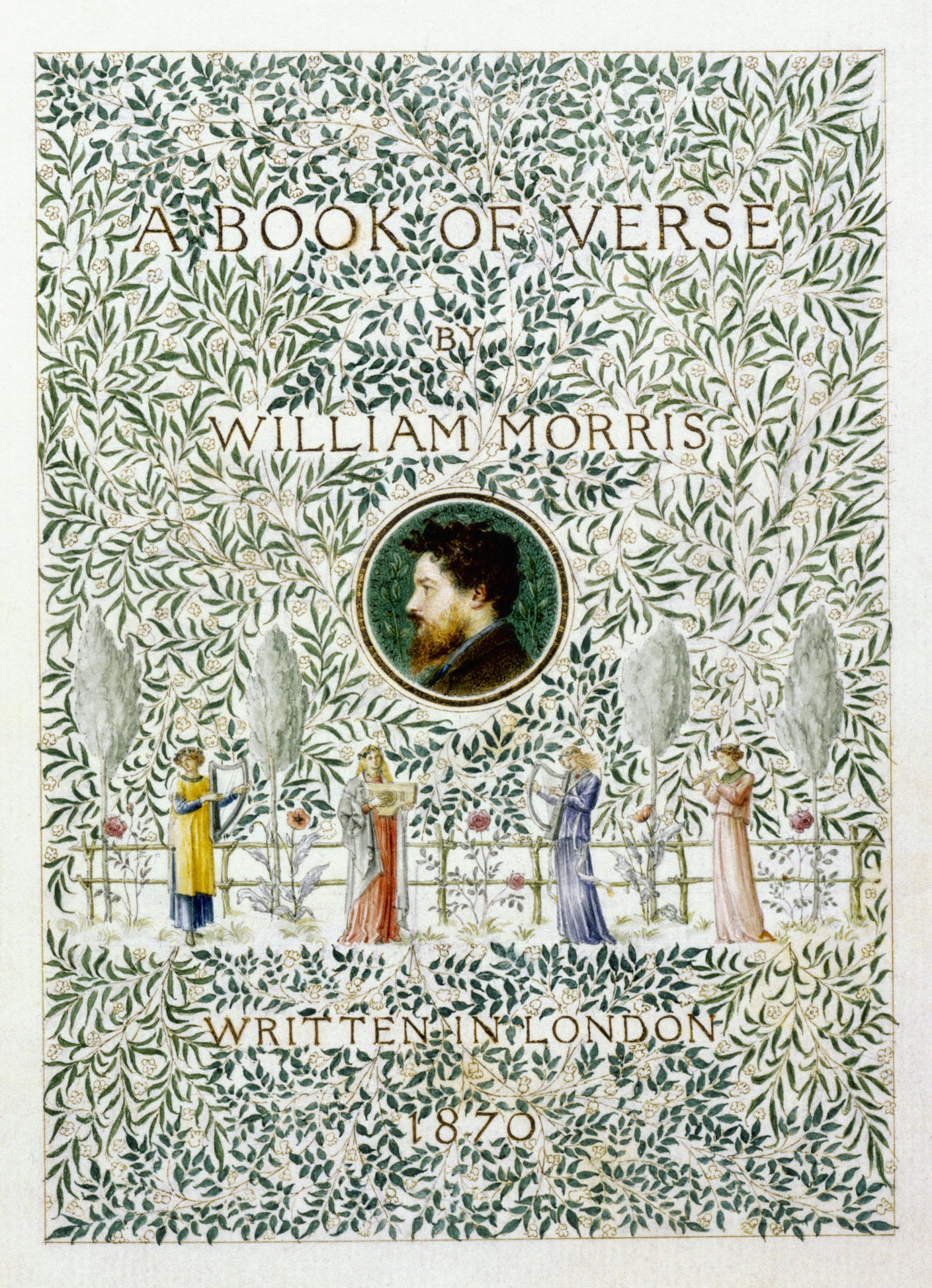

Morris first published a selection of his best poems in 1858 — based on the legends of King Arthur — called The Defence of Guenevere. This Arthurian theme continued when he became one of a group of young artists to decorate the new Oxford Union debating hall with murals.

As the artists were their own models, Morris commissioned a blacksmith to build him a suit of armour, and — according to Burne-Jones — when he tried on the helmet, the visor stuck closed. Happily, after solving the problem, Morris found the armour much to his liking, wearing it at dinner.

At Oxford, he met and fell in love with Jane Burden — the classically beautiful daughter of a local groom, who became a much-admired artist’s muse and a gifted embroiderer — and they married on April 26, 1859.

None of the Morris family attended, feeling the match to be socially unsuitable. In 1860, the couple moved to the Arts-and-Crafts Red House in Upton, near Bexleyheath, Kent, co-designed by Morris and Philip Webb.

Initially, life was happy and Morris took to designing in earnest. Despite his dislike of children, two daughters were born — Jane, always known as Jenny, and Mary, called May.

Morris was a kind, proud father, saying later that his girls were ‘very sympathetic with me as to my aims in life’. Burne-Jones wrote that: ‘Top [his name for Morris] is slowly making Red House the beautifullest place on earth.’

However, the designer’s hopes of marital felicity were dashed when, from 1862, Jane and Rossetti began a long affair. Morris, anguished, threw himself into his work, attempting to distance himself from the troubled marriage.

The aim of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co, a collaboration between Morris and the friends who had decorated the newly built Red House, was to produce everything needed to decorate a home.

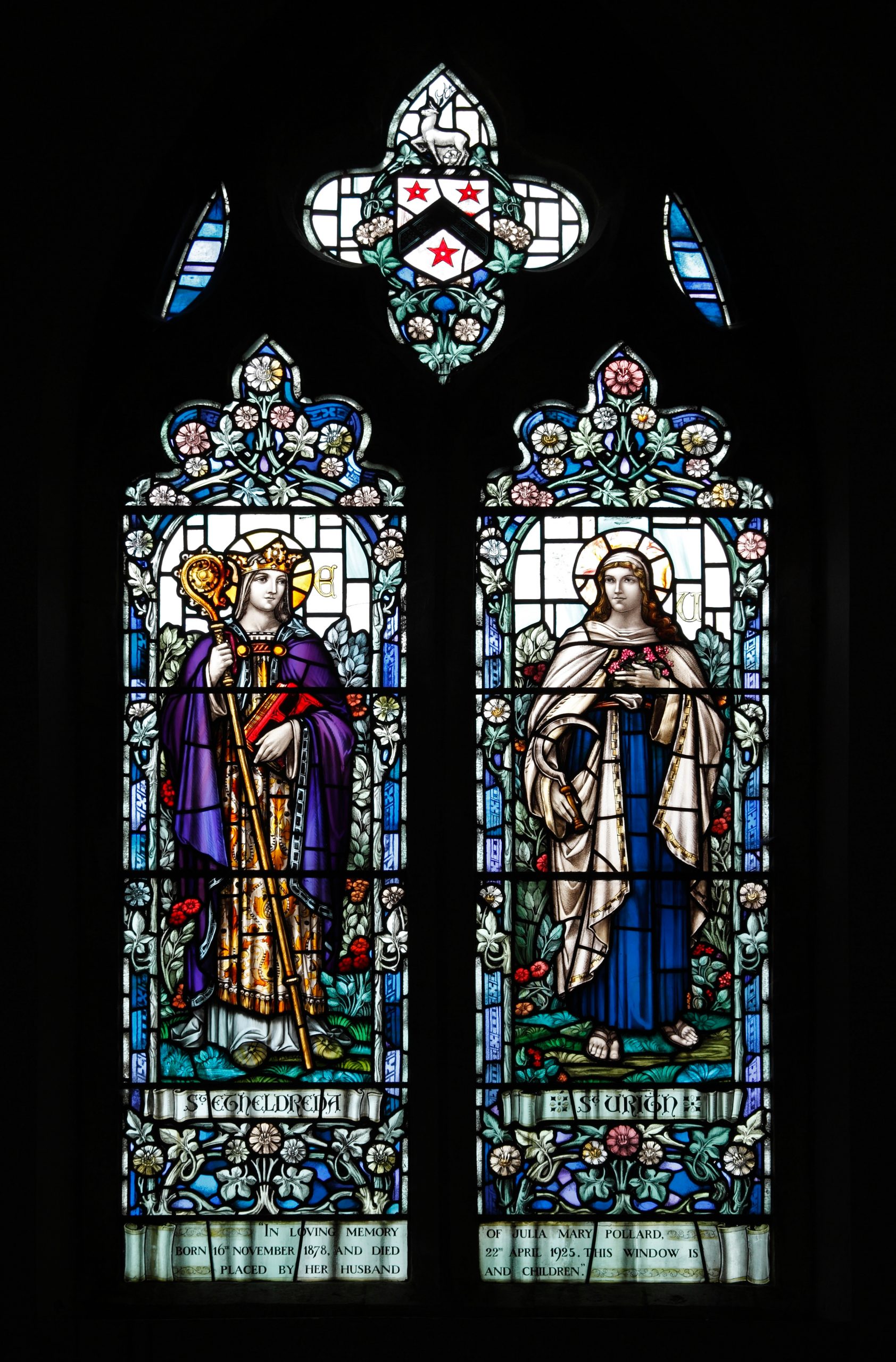

They were true amateurs in every sense, not least the chaotic financial management of the business. At first, they produced stained glass and ecclesiastical-style embroideries (many stitched by Jane) — winning gold medals for both at the 1862 International Exhibition in London — and subsequently began to produce hand-painted tiles, furniture and wallpapers.

Start-up capital was miniscule, with each member having a £1 share — later increased to £20 — and Mrs Morris Snr loaning £100.

Initially, Faulkner, who dealt with the accounts, and Morris were both paid an annual salary of £150, with everyone else being paid under the piece-rate system.

However, only five years after moving into their carefully crafted retreat, which Rossetti described as ‘more a poem than a house’, the Morrises took up residence above the company premises at 26, Queen Square in Bloomsbury.

Morris had been gravely ill with rheumatic fever in 1864 and, afterwards, found the commute from Kent exhausting. The fact that the Red House — which had been built facing predominantly north — was always cold in winter was a problem, too. The family’s beloved home had become a burden and, after leaving, Morris never returned — his emotional attachment proving too strong.

Although wallpapers were popular products of The Firm, Morris, who preferred to have embroideries on his walls, considered them ‘makeshift’.

Still, he appreciated that they offered easily affordable home decoration and went on to design 41 wallpapers and five ceiling papers. Not cheap to produce, each needed at least 12 design blocks and some up to 30.

In 1866, The Firm was invited to decorate the Armoury and Tapestry Rooms at St James’s Palace in London, as part of a contract that also included re-papering the Entrée Room, Ballroom and Banqueting Room. Later, in 1879, they worked on The Queen’s, Ambassadors’ and Grand Staircases, producing a unique wallpaper. Work at the palace continued from 1881, when they redecorated the Guard Room, Throne Room, the Yellow and Blue Rooms, Boudoir and Reception Room.

The palace was their most high-profile commission, but others included working at Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, and Naworth Castle, Cumbria.

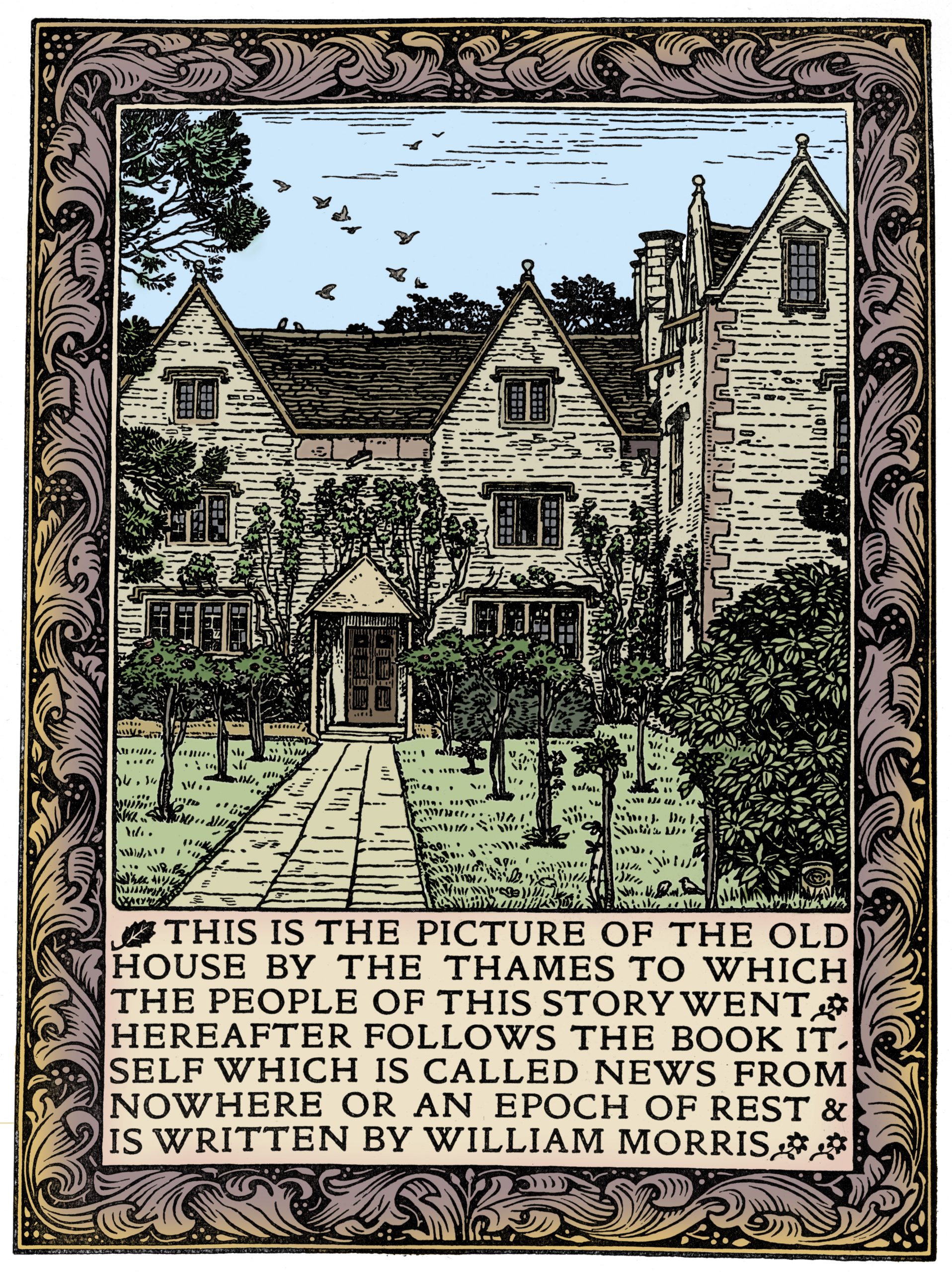

Somewhat strangely, Morris took on the tenancy of Kelmscott Manor near Lechlade in Gloucestershire in 1871, which he shared with his wife’s lover, Rossetti, for three years before the artist moved out. As he did the Red House before, Morris loved Kelmscott, calling it ‘Heaven on Earth’.

In 1875, the firm was completely reorganised, bringing it under the sole control of Morris, who renamed it Morris & Co. New showrooms opened at the corner of Oxford Street and North Audley Street and the cabinetmaking workshop was moved to the former premises of the renowned 19thcentury firm Holland in Pimlico.

The showroom staff were invaluable when more of Morris’s time was being taken up by lectures on design and socialism, as well as a new interest, the Kelmscott Press, which he opened in 1891.

Opposed to modern printing practices, he wanted to revive the artistic style of medieval manuscripts. The Kelmscott Chaucer, produced in 1896, is considered one of the finest books ever made.

Eventually, all The Firm’s manufacturing moved to Merton Abbey, near Morden in Surrey, in 1881. Seven miles from central London, it was a quiet rural setting and clear water from the River Wandle was perfect for dyeing material.

Some fabrics produced there — such as the oak-pattern damask at 45 shillings a yard and the Granada woven and cut velvet for £10 a yard — were very expensive for the time. Morris’s poetry continued to be well regarded, too.

When Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the poet laureate, died in 1892, the designer was under consideration for the post, which went to Alfred Austin, although Morris was rumoured to be the favourite of Queen Victoria.

During the 1890s, his health began to decline. A voyage to Norway in the summer of 1896 failed to revive it and on October 3, Morris died at his London home, Kelmscott House, at the age of 62.

His doctor said that his cause of death was ‘simply being William Morris and having done more work than most 10 men’. Burne-Jones had thought that his friend ‘never seemed to be particularly busy’, but clearly he was wrong.

Morris’s hard work allowed people to follow his famous maxim of 1880: ‘Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.’

For the current incarnation of William Morris’s company, visit morrisandco.sandersondesigngroup.com

Morris: a man of many talents

- His iconic Strawberry Thief pattern, first produced in 1883 and still available, was inspired by thrushes that Morris caught stealing fruit from his garden

- Morris’s wife, Jane, modelled for his only surviving easel painting, La Belle Iseult — now in the Tate Gallery — in 1858, the year before they were married

- The pattern known as Snakeshead Fritillary dates from 1876 and was a particular favourite of Morris himself

- The magnificent series of stained-glass windows designed by Burne-Jones and Morris for Jesus College Chapel, Cambridge — together with the ceiling painted by Morris and Webb — is considered to be the pinnacle of The Firm’s work

- As a poet, Morris is perhaps best known for his romantic narrative The Life and Death of Jason (above, 1867) and The Earthly Paradise (1868–70), a series of narrative poems based on classical and medieval sources

- In the 1870s, Morris made several trips to Iceland, where he recorded some of his most vigorously descriptive writing in a series of journals

- Morris’s talents were not confined only to wallpaper and textiles. After acquiring the Kelmscott Press, he designed three type styles: Golden type, modelled on that of Nicolas Jenson, the 15th-century French printer; Troy type, a Gothic font on the model of the early German printers of the 15th century; and Chaucer type, a smaller variant of Troy

In Focus: The art of Ford Madox Brown

Known for his bold and thoughtful pictures, as well as a fondness for magenta, Ford Madox Brown was one of

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.