My Favourite Painting: Zaha Hadid

Zaha Hadid chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

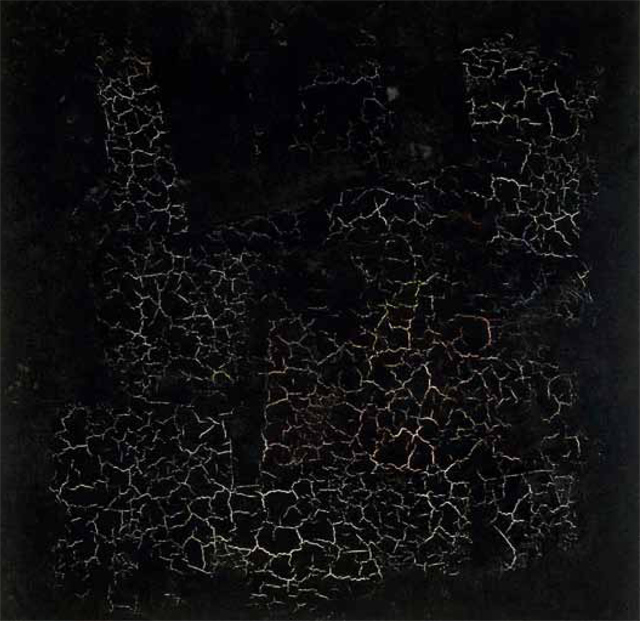

Black Square (first version), 1915, 31in by 31in, by Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), State Tretyakov Museum, Moscow. Bridgeman Images.

Zaha Hadid says: 'In the Russian avant-garde exhibition we designed at the Guggenheim, New York (‘The Great Utopia’, 1992), there was almost a religious moment when we opened the crate with Malevich’s Black Square. Every curator in the Russian world was there to witness it. We had to open the box at 2am, and then hang the painting. It was an interesting moment historically, as it was just after Russia and the Soviet republics had opened up, allowing so many works to be borrowed from institutions under one umbrella. To do that show again would be almost impossible now, as you’d have to borrow works from so many places.'

Dame Zaha Hadid is an architect whose recent works include the Aquatics Centre in the Olympic Park

Art critic John McEwen comments: 'The late John Golding, authority on Cubism, wrote of the pictorial cube Black Square that ‘for all its boldness and simplicity’, it ‘has ultimately defied analysis’. There are three later pictorial versions. Malevich was the son of Polish emigrants to Ukraine, and his father was a foreman in a sugar-refining factory. The artist harboured a great respect for the peasantry of his rural childhood; also for his (probably illiterate) mother.

In every Orthodox Russian home, there is a sacred-icon corner, and it is spiritually symbolic of his tabula rasa that, for all his Catholic upbringing, Malevich placed it iconically across a corner when first exhibited. Perhaps Patrick Leigh-Fermor comes closest to explaining the artist’s spiritual transference when he talks of the Orthodox image of ‘the All Powerful Christ Pantocrator’ being ‘as transcendant as the regions of abstract thought’. Malevich’s transcendance was abstraction itself. Malevich’s art movement, Suprematism, aspired to ‘the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art’. It was inspired by technology, especially aviation, which, he wrote, meant one could ‘refer to Suprematism as “aeronautical”’.

The black square was his emblem. It was hung over his bed as he lay dying, brandished on the banner that led his funeral procession and decorates his gravestone. Denied for many decades of Soviet state art, today—enshrined in the Hermitage and the Tretyakov—it has truly ‘iconic’ status in Russia. For Zaha Hadid, Black Square introduced the idea of ‘the world itself’ as ‘the site of pure, unprejudiced invention’.'

This article was first published in Country Life, September 5, 2012

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.