My Favourite Painting: Lucinda Bredin

Lucinda Bredin chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

Self-Portrait with Two Circles, 1665–69, by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–69), The Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood House, London. Bridgeman Images.

Lucinda Bredin says: ‘Kenwood was one of the places on our itinerary. My father would pick me up in his Hillman Minx and drive to Kenwood House, which, to imbue it with more glamour, he said belonged to Princess Margaret. It was also the home of my favourite painting. A lonely child, I could see that Rembrandt had had his problems. He looked as if he’d knocked about a bit, but he also seemed to be willing to share stories with me. Even now, I occasionally run things past him. He always listens.’

Lucinda Bredin is Arts editor of The Week and editor of Bonhams Magazine.

Art critic John McEwen comments: 'Through his many self-portraits, we know what Rembrandt looked like to a degree unmatched in art. From his first etched likeness as a curly mopped 21 year old to his last in oils the year he died, he charted his appearance in more than 80 paintings, drawings and etchings. In that time, he suffered the deaths of his two wives, four of his five children and, aged 50, was declared bankrupt through ‘losses suffered in business as well as damages and losses at sea’.

Self-portraits in the 17th century were not a private indulgence, but one more commercial genre, sold together with other subjects. Although he was only in his twenties, three of Rembrandt’s self-portraits were held in grand collections, including that of Charles I. When he was bankrupted, not one appears on the inventory of his possessions. Before the 19th century, and the dawning of psychology, ‘self-portraits’ were described as pictures of artists by their own hand. But if there were no psychoanalysts in Rembrandt’s day, philosophy and religion—not least the seven deadly sins—were cause enough for self-examination.

Rembrandt could empathise inimitably with the sufferings of Christ, so he has the profoundest understanding as a witness of his own mortality. ‘Old age is a shipwreck,’ said Gen de Gaulle. Rembrandt unflinchingly recognises this, but with a compassionate, rather than a cold, eye. His face registers as many emotions as we bring to it. The significance of the famous circles is a mystery, except that this great painting would not be quite so magisterial without them.'

This article was first published in Country Life, February 10, 2010

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comeback

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comebackThe Kentish glory moth has been absent from England and Wales for around 50 years.

By Jack Watkins

-

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?It was the home of Mr Gruber and his antiques in the film, but in the real world, Alice's Antiques could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

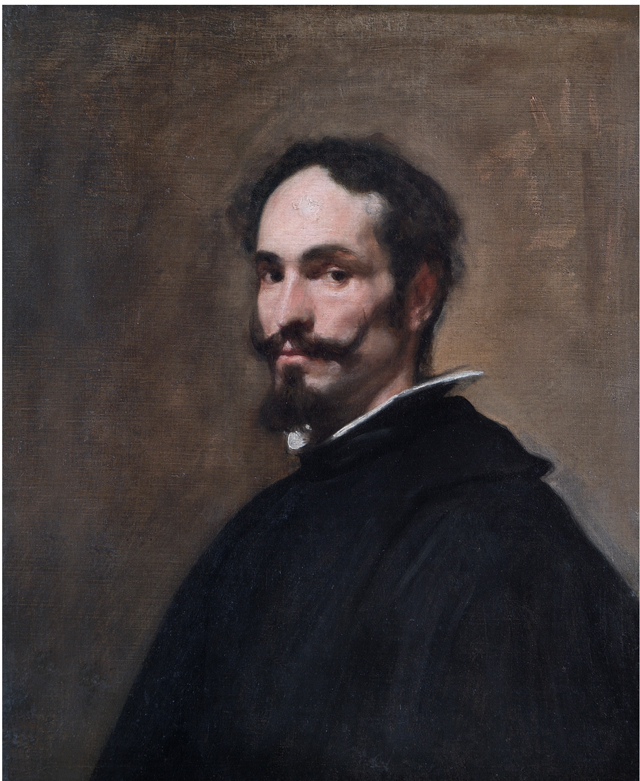

My favourite painting: Allan Mallinson

My favourite painting: Allan MallinsonMilitary historian Allan Mallinson picks an image of 'faith, generosity and ultimate sacrifice'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

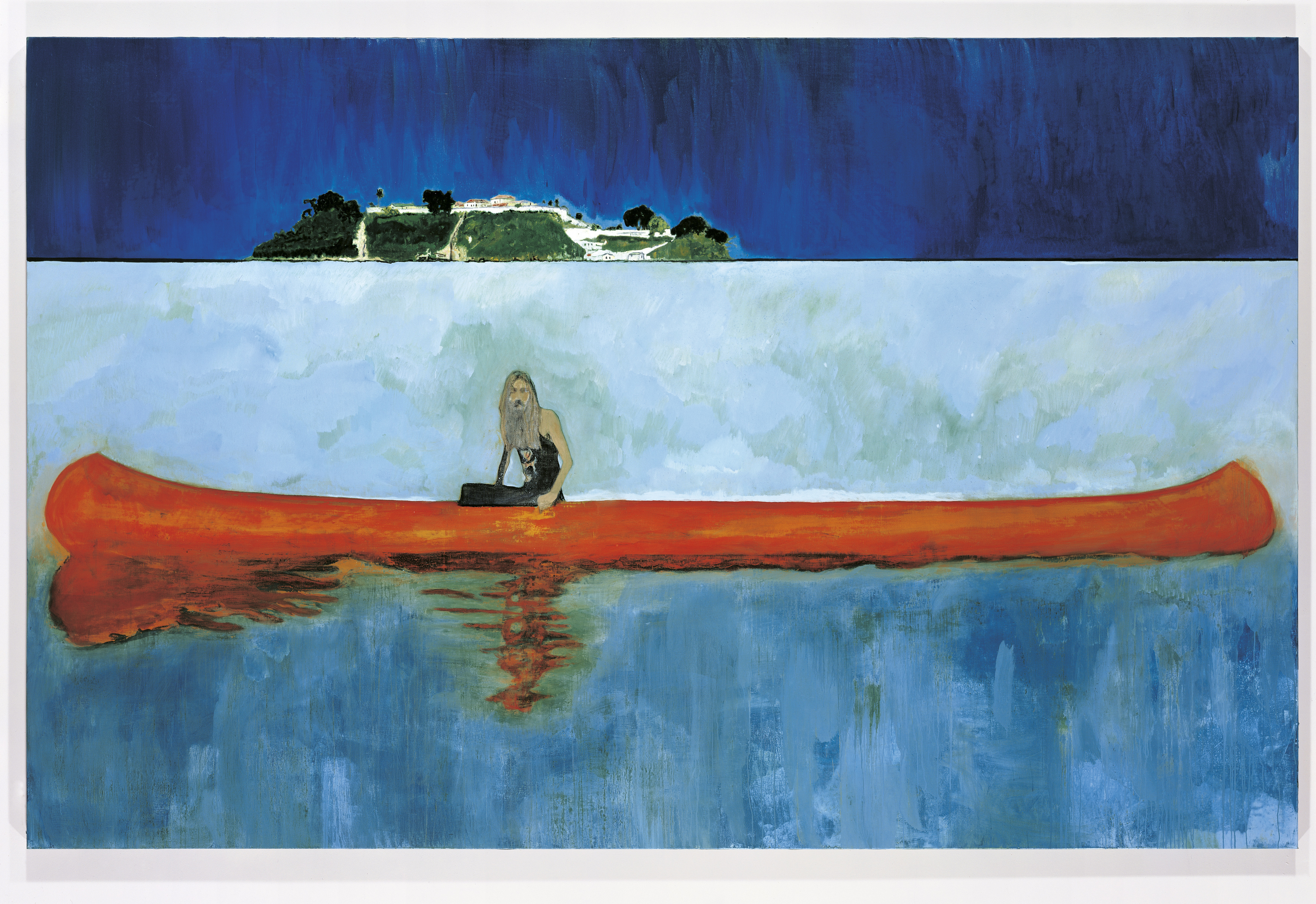

My Favourite Painting: Piet Oudolf

My Favourite Painting: Piet Oudolf'One cannot sense whether he is far out on the ocean or closer to shore, or what he may be watching or feeling in that moment as he stares towards the beach.’

By Country Life

-

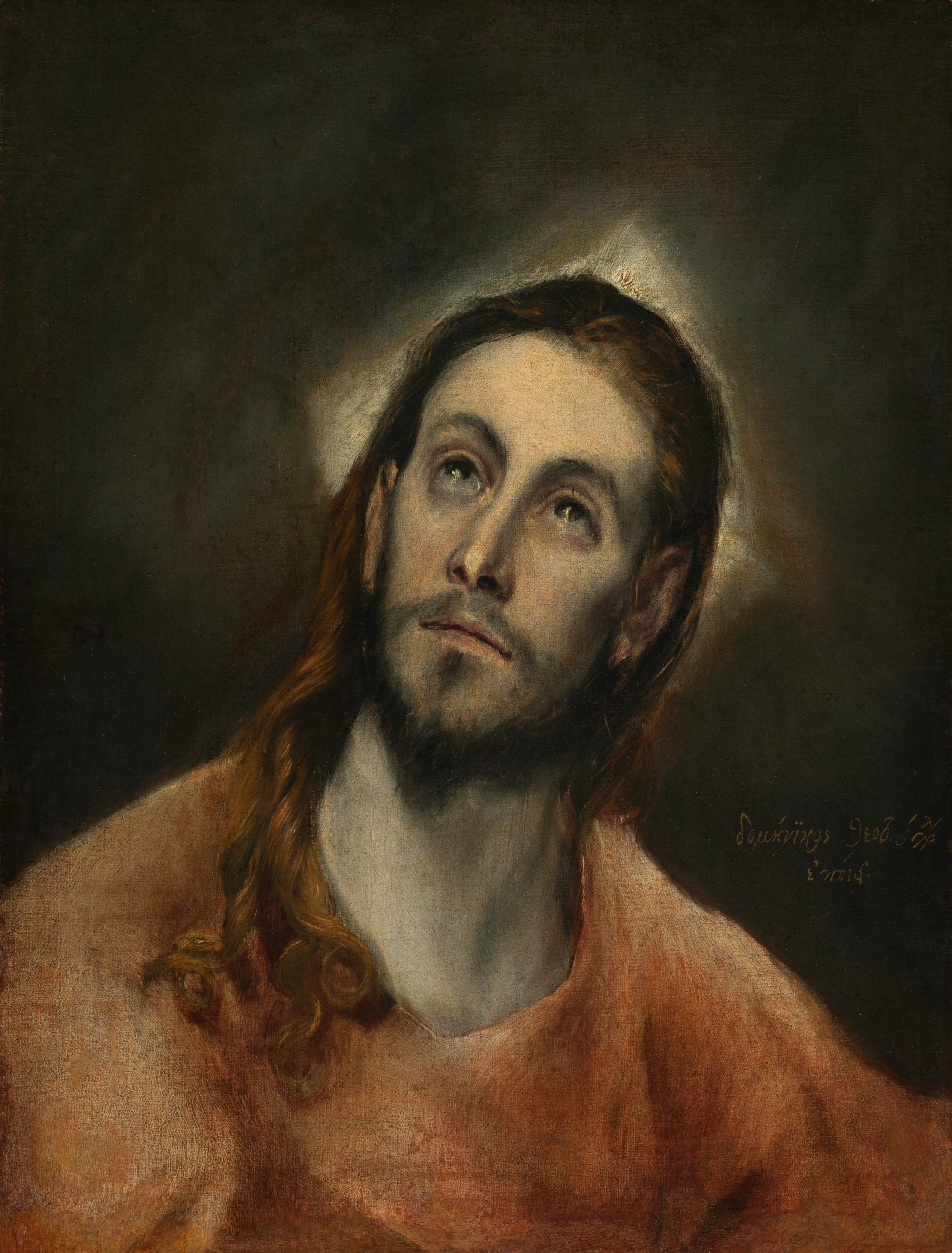

My Favourite Painting: Mary Plazas

My Favourite Painting: Mary Plazas'There is compassion, awe, humility, a knowing yet a questioning in the glistening eyes. It moves me, it inspires me beyond the need to know.’

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Robert Kime

My favourite painting: Robert KimeRobert Kime shares his fondness for New Year Snow by Ravilious

By Country Life

-

My Favourite Painting: Anna Pavord

My Favourite Painting: Anna PavordAnna Pavord chooses a picture which reminds her of where she grew up

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: The Duchess of Wellington

My favourite painting: The Duchess of WellingtonThe Duchess of Wellington chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Maureen Lipman

My favourite painting: Maureen LipmanMaureen Lipman chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Jacqueline Wilson

My favourite painting: Jacqueline Wilson'I looked at this painting and decided to write about a Victorian circus girl one day'

By Country Life