My Favourite Painting: Frank Gardner

Frank Gardner chooses his favourite painting for Country Life

The Marriage of an Arab in Cairo, 1869, about 18in by 12in, by Henri de Montaut (1830–about 1890). Bridgeman Images.

Frank Gardner says: 'The costumes may have changed, but the spirit of this 19th-century picture was exactly the same when I arrived in Cairo to live there as a student more than 100 years later. I moved in with a large Egyptian family, living in a ramshackle loft in a street exactly like this in a quarter called Khan Gaafar. They kept pigeons on the roof. At night, they would invite me in for backgammon, hubbly-bubbly pipes or a wedding party such as this. Once, someone got over-excited and fired a pistol that brought down some masonry close to the bridegroom’s head and there was a fearful row. But it was all part of the fun of living in what was still effectively a medieval city quarter.'

Frank Gardner is Security Correspondent for the BBC

Art critic John McEwen comments: 'Through Muslim invasion and colonisation, Europe had long been familiar with Arab culture. But Orientalism, the fashion for everything exotically Arabian, did not reach its zenith until the second half of the 19th century. European occupation, colonisation, the advance from grand tours to tourism all stoked the vogue.

By the 1840s, there were western hotels in Cairo and, by 1868, Thomas Cook tours went as far south as Aswan. This unsigned lithograph by French artist Henri de Montaut comes from his Egypte Moderne: Tableaux de Moeurs Arabes Peintes et Descrites. Scenes of souks and bazaars allowed painters to whet the appetites or nurse the memories of tourists. Off-limit harems gave scope for through-the key-hole fantasies of naked beauties cavorting inside. Clamorous wedding processions offered a public spectacle. Orientalism was especially popular in France and England, reflecting imperial interests. In painting, it began with Delacroix and Ingres, and reached a sensuous apogee in the 20th century with Matisse. Lawrence Durrell’s novel The Alexandria Quartet provided a sumptuous Orientalist counterbalance to 1950s postwar austerity.

Apart from exoticism, the Muslim world had the romantic appeal of appearing to survive from an older, purer time. Eugene-Melchior de Vogü. was just one writer who noticed ‘the intellectual and social horizons of the Islamic world are in many respects comparable to those of our medieval forefathers’. Neo-Gothic architecture, which enjoyed its 19th-century revival as a link with the Age of Faith and the inspiring example of the great cathedrals, was also sometimes considered Islamic in origin.'

This article was first published in Country Life, April 25, 2012

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?The King's recent visit to Nansledan with the Prime Minister gives us a clue as to Labour's plans, but what are the benefits of traditional architecture? And can they solve a housing crisis?

By Lucy Denton

-

The battle of the bridge, Balloon Dogs and flat fish: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 15, 2025

The battle of the bridge, Balloon Dogs and flat fish: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 15, 2025Tuesday's quiz tests your knowledge on bridges, science, space, house prices and geography.

By James Fisher

-

My favourite painting: Allan Mallinson

My favourite painting: Allan MallinsonMilitary historian Allan Mallinson picks an image of 'faith, generosity and ultimate sacrifice'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

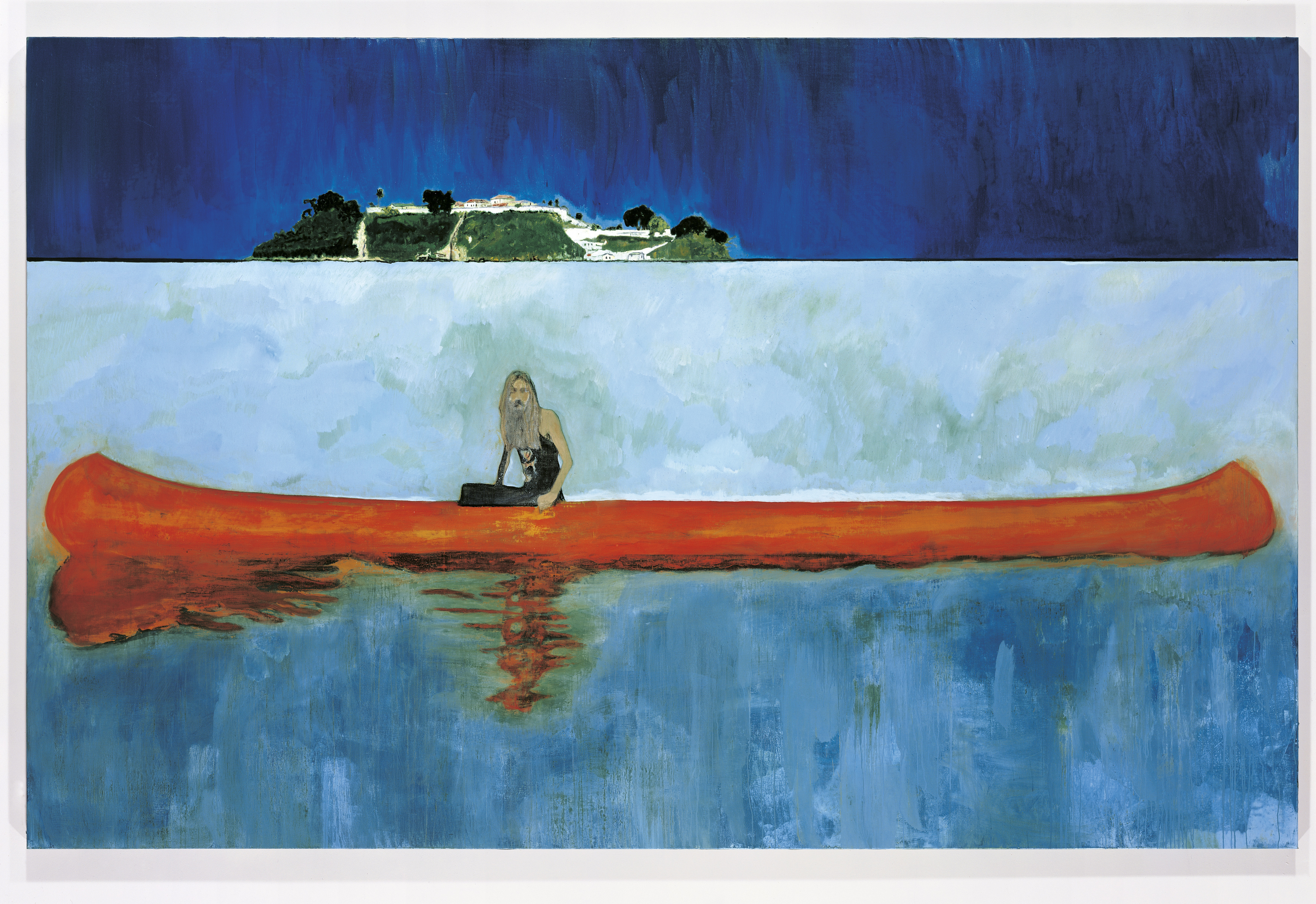

My Favourite Painting: Piet Oudolf

My Favourite Painting: Piet Oudolf'One cannot sense whether he is far out on the ocean or closer to shore, or what he may be watching or feeling in that moment as he stares towards the beach.’

By Country Life

-

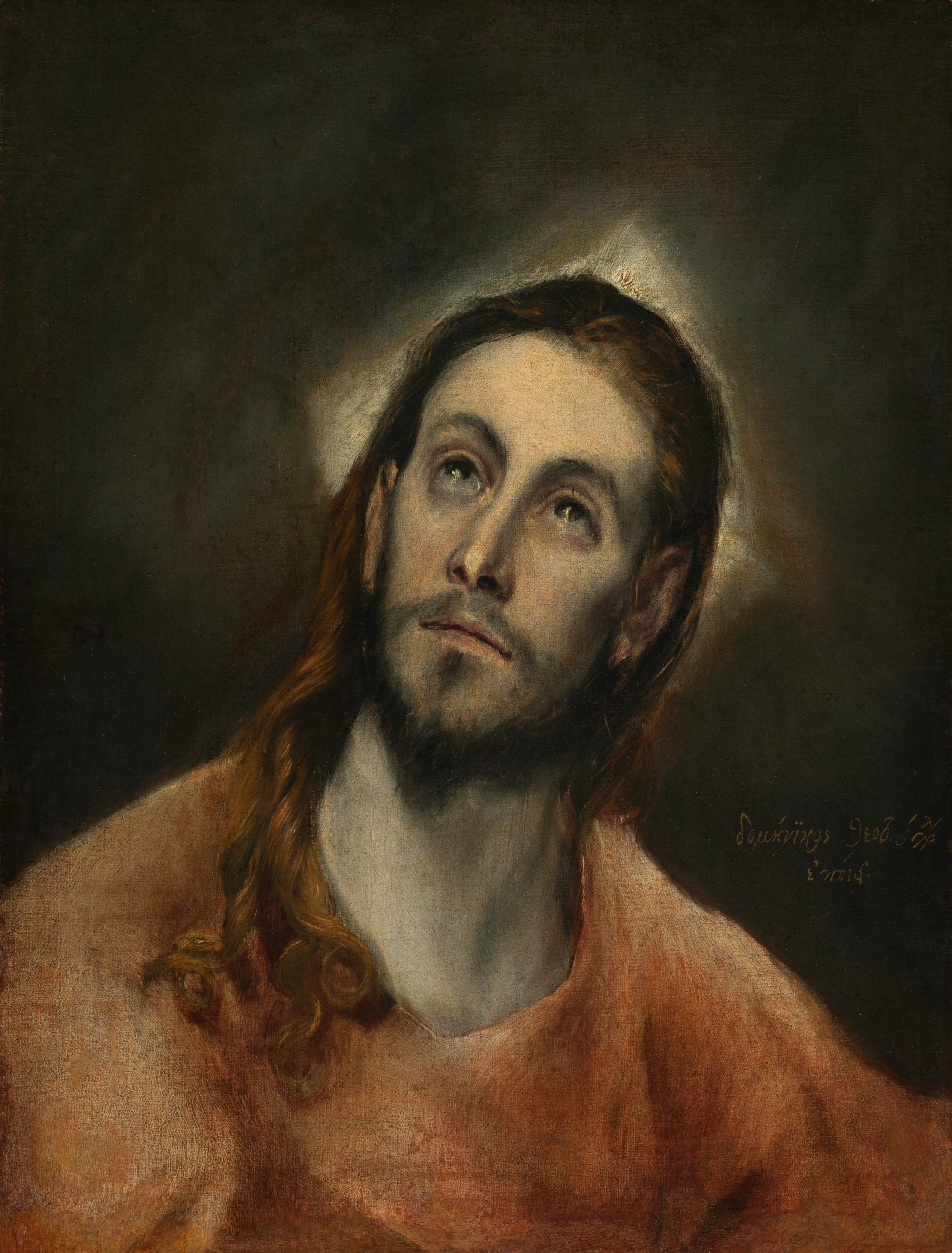

My Favourite Painting: Mary Plazas

My Favourite Painting: Mary Plazas'There is compassion, awe, humility, a knowing yet a questioning in the glistening eyes. It moves me, it inspires me beyond the need to know.’

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Robert Kime

My favourite painting: Robert KimeRobert Kime shares his fondness for New Year Snow by Ravilious

By Country Life

-

My Favourite Painting: Anna Pavord

My Favourite Painting: Anna PavordAnna Pavord chooses a picture which reminds her of where she grew up

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: The Duchess of Wellington

My favourite painting: The Duchess of WellingtonThe Duchess of Wellington chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Maureen Lipman

My favourite painting: Maureen LipmanMaureen Lipman chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Jacqueline Wilson

My favourite painting: Jacqueline Wilson'I looked at this painting and decided to write about a Victorian circus girl one day'

By Country Life