My Favourite Painting: Basil Comely

Basil Comely chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Venetia, Lady Digby, on her Deathbed, 1633, 29in by 32in, by Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), Dulwich Picture Gallery, London. Bridgeman Images.

Basil Comely says: 'My mother, Barbara, died four months ago. In a way I couldn’t have imagined, a deathbed can have beauty and meaning alongside the worst. Venetia was painted dead, but van Dyck seems to capture her as she nears her last. She looks beautiful, she looks knowing–so did my mother. She wears her jewellery–so did my mother. Venetia is young, my mother was old, but clouds lifted. And if you avoid the horrors of a hospital death, there’s a timelessness of pillow and coverlet. She would like this picture. A wonderful memento mori. And now, in a way, so is this page.'

Basil Comely is head of London Arts at the BBC. His new series Heritage! The Battle for Britain’s Past begins at 9pm, March 7, on BBC4.

Art critic John McEwen comments: 'John Aubrey’s Brief Lives is the main source for the scarlet reputation of the beautiful Venetia Digby (1600–33). The child of the daughter and co-heiress of the Duke of Northumberland, she became, he claims, a teenage courtesan and had two children as ‘concubine’ of the 4th Earl of Dorset, who left her an annuity of £500. In 1624, she married Sir Kenelm Digby (1603–65), courtier, diplomat, intermittent Catholic and amateur scientist. He was smitten and determined to restore her reputation: ‘A wise man, and lusty, could make an honest woman out of a brothel house.’

The married Venetia ‘carried herself blamelessly yet (they say) he was jealous of her’. This may explain the suspicion that he killed her, although it seems more likely her unexpected death came from taking one of his experimental potions, supposedly a beauty treatment concocted from viper’s blood. Digby was a patron of van Dyck, who provided this idealised memento mori of her two-day-old corpse. The slightly open ‘far-seeing’ eye is a genre convention; pearls, rouge and the withered rose are obvious ornaments.

Digby kept the picture by his bed, ‘the only companion I now have’. When she died, van Dyck was still at work on her full length portrait, now in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG). She holds a live serpent (grim irony, as things transpired) symbolising wisdom and he clothes her partly in black to acknowledge her demise. Also in the NPG are two paintings of the piggy-faced Digby (one by van Dyck), who became ‘the most accomplished cavalier’ in the Civil War.'

This article was first published in Country Life, February 27, 2013

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwards

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwardsCampaigners in England often point to Scotland as an example of how brilliantly Right to Roam works, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, says Patrick Galbraith.

By Patrick Galbraith

-

My favourite painting: Allan Mallinson

My favourite painting: Allan MallinsonMilitary historian Allan Mallinson picks an image of 'faith, generosity and ultimate sacrifice'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Piet Oudolf

My Favourite Painting: Piet Oudolf'One cannot sense whether he is far out on the ocean or closer to shore, or what he may be watching or feeling in that moment as he stares towards the beach.’

By Country Life

-

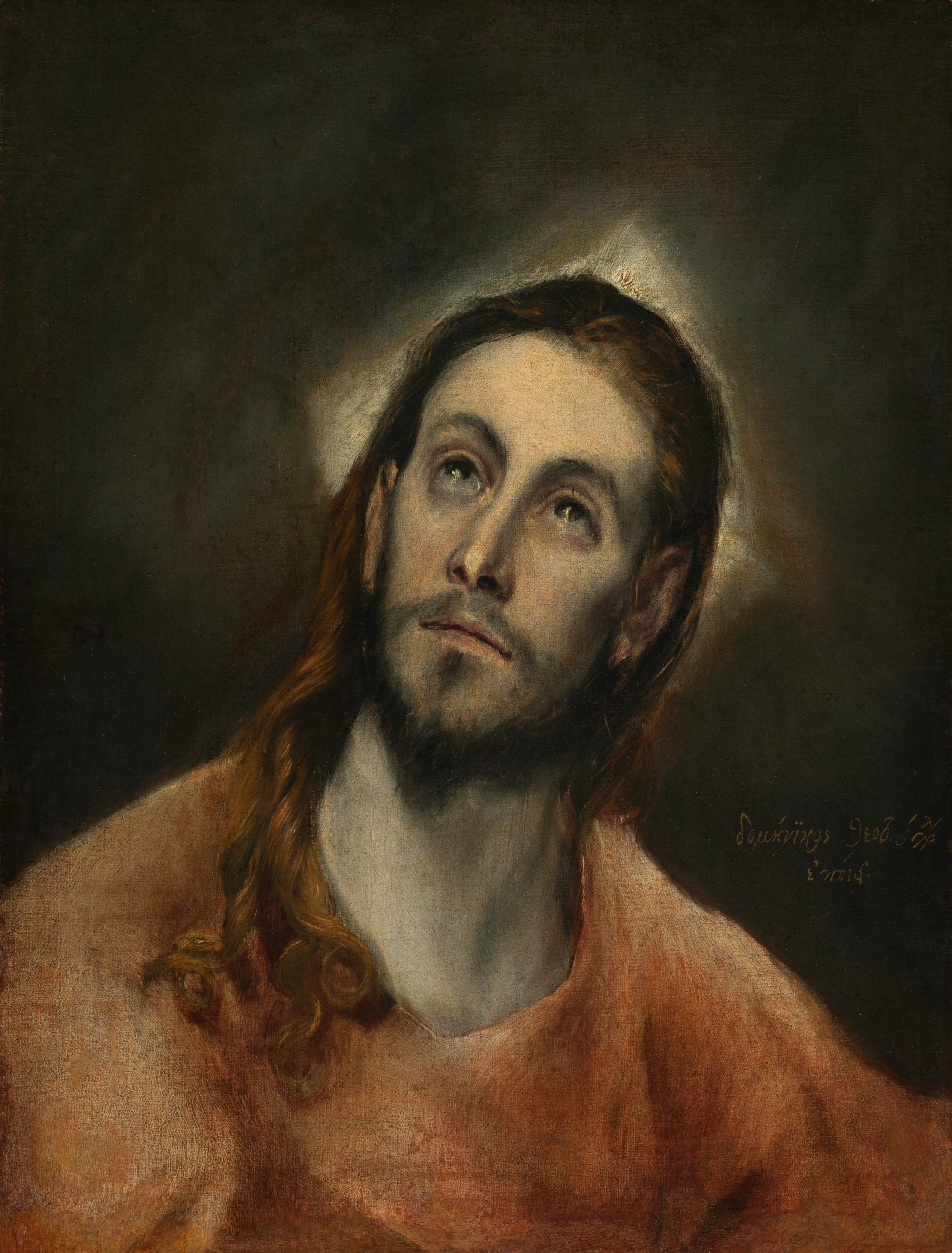

My Favourite Painting: Mary Plazas

My Favourite Painting: Mary Plazas'There is compassion, awe, humility, a knowing yet a questioning in the glistening eyes. It moves me, it inspires me beyond the need to know.’

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Robert Kime

My favourite painting: Robert KimeRobert Kime shares his fondness for New Year Snow by Ravilious

By Country Life

-

My Favourite Painting: Anna Pavord

My Favourite Painting: Anna PavordAnna Pavord chooses a picture which reminds her of where she grew up

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: The Duchess of Wellington

My favourite painting: The Duchess of WellingtonThe Duchess of Wellington chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Maureen Lipman

My favourite painting: Maureen LipmanMaureen Lipman chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

By Country Life

-

My favourite painting: Jacqueline Wilson

My favourite painting: Jacqueline Wilson'I looked at this painting and decided to write about a Victorian circus girl one day'

By Country Life