Drovers' routes: The ancient trails from farm to market, and how they've shaped our roads to this day

In driving cattle, sheep and geese to market over the centuries, drovers shaped many of the routes we still use today. Gavin Plumley charts their harsh journeys on the drovers across the country.

In an age of satnav and increasingly automated cars, little thought is given to the roads on which we travel. But whether you’re popping to the shops or disappearing for the weekend, you’re doubtless journeying down a path that has existed for centuries. Some, including defiantly straight incisions through the countryside, were left by the Romans; others are evidence of another tribe that has since vanished from our landscape.

The drovers were responsible for carving an extraordinary network through Britain, dating from at least the 12th century. This impressive group of farmers came from the uplands of Wales, as well as Cumbria and Scotland, from where they drove their livestock to distant markets. Their routes are now sections of the A5 in Snowdonia and the A44 through Powys and the Heart of England, as well as the A1 and the winding A303. Yet, however much the traffic jams past Stonehenge test our patience, they are nothing compared with the arduous life of a drover.

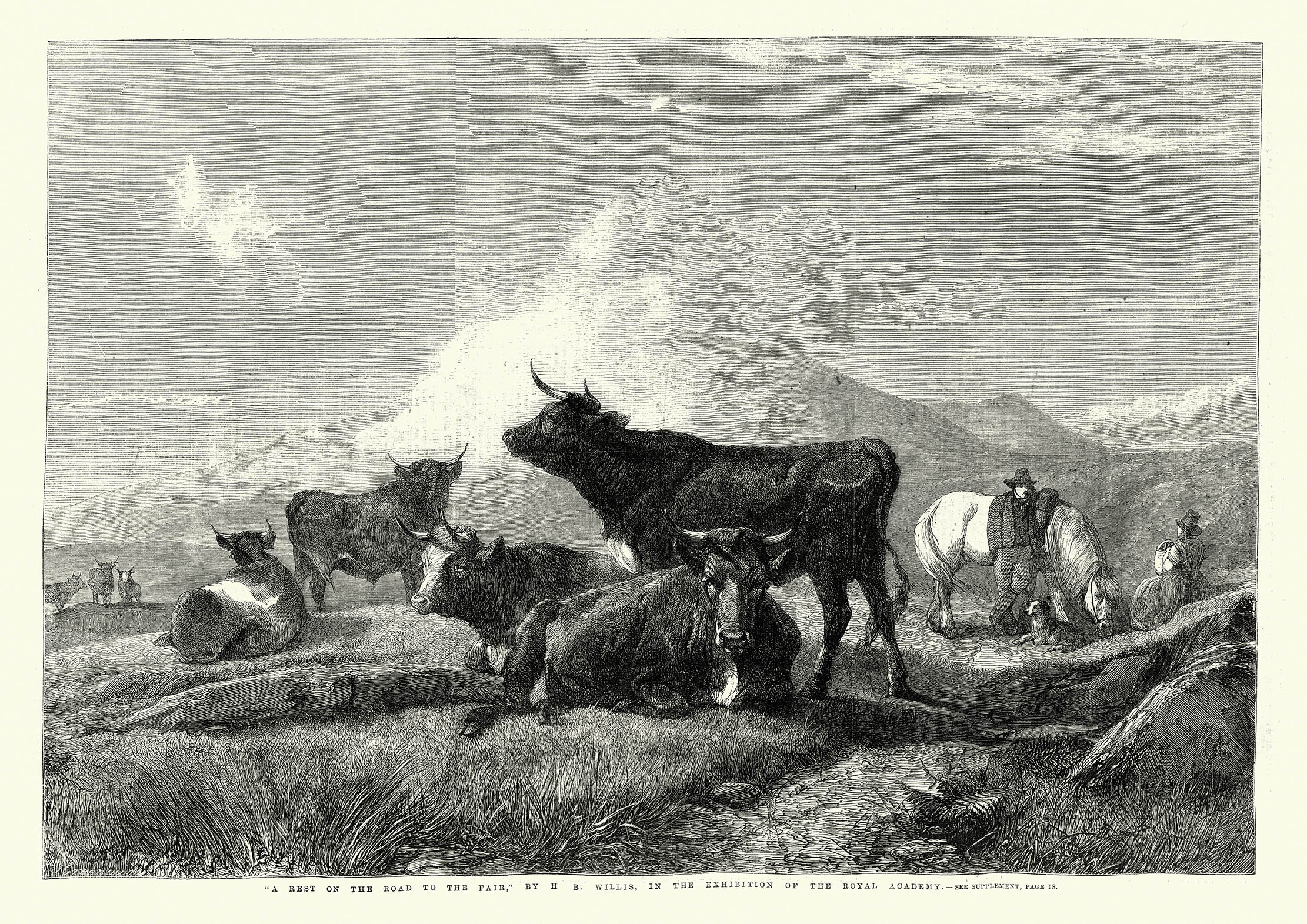

A single journey could take several weeks and often included a spectacular number of animals, flocks of geese, herds of cattle, bleating sheep. Such was the size of the convoys that they could block the roads for hours, accompanied by deafening levels of noise. Locals were duly warned of the herd’s approach, but the combination of mooing cows and barking dogs, as well as the farmer’s hallooing, singing and shouting, was hardly the stuff of pastoral pleasure.

Avoiding the height of summer and winter’s deepest snow, the processions would leave home with their sights set on the South-East. Although Welsh livestock came from various corners of the country, including Pembrokeshire and Anglesey, many cows’ journeys began around Tregaron, where lush grass fattened the animals for the trek ahead. Having gathered outside the (still extant) Talbot Inn, with beer aplenty and a shoeing field for the farmer’s horses and cattle, most packs set off east.

The first challenge was the Cambrian Mountains. Formed of mudstone and sandstone, with deposits of lead, zinc, silver and even gold, the heart of the range commands several evocative names. In Welsh, the area’s nigh-exclusive tongue, it is known as Elenydd (the area around the source of the Elan), although more poetic minds have called it ‘Gwalia deserta’, the wilderness of Wales. Here, high above reservoirs and dams, is a vast moorland.

During the warmer months, the place shimmers like a Celtic Sahara, as heather scratches the shins and the bilberries, with their shots of sherbet, are left desiccated in the heat. Come the darker half of the year, the wilderness turns wilder, when local ewes are forced to shelter from winds bringing rain up the slopes from the Irish Sea.

The livestock taken across these uplands by the drovers had no choice, however, as corgis and other dogs bit their heels to impel them onwards. And although the mountain passes were strenuous, they offered the best, if bleakest option — so bleak, in fact, that the area provided locations for the Welsh crime drama Hinterland.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Climbing over these hills certainly meant the drovers avoided potentially hostile valley farmsteads, where landlords were keen to protect their own. Below, too, were tolls at junctions and bridges. But these were also places that provided stopovers and provisions, giving rise to names such as ‘Oxpen’ and ‘Halfpenny Field’, with pastures enriched by the passing herds’ manure.

Cattle would have to be shod repeatedly on the journey — geese likewise wore shoes to protect their webbed feet — in turn prompting a whole arrangement of smithies. The chapel at Bwlch-y-rhiw, between the sources of the Cothi and Tywi, where my grandparents are buried, just below their old farm, was the site of an old forge. Sometimes, the drovers would join the worshippers, as at Soar y Mynydd, an even lonelier chapel amid the mountains to the north.

The cowboys have gone, of course, but their box pews remain, as do the Scots pines they planted in the graveyard. Towering above the landscape and clipping the fledgling swallows in summer, the trees were important markers right across Britain. Capable of growing on poor soil, the pines could be seen for miles. They often denoted intersections or places of rest, including inns and friendly farms.

Once across the stark Welsh plateaus and the border towns beneath, including my own Herefordshire village of Pembridge, the drovers soon converged. Like capillaries, veins and arteries, their routes inevitably led to the system’s major organs. Some markets were nigh, such as Hereford and Worcester, although more considerable gains were to be found at Smithfield in London, once one of the largest meat markets in the world — and the name for several Welsh streets. But there were other targets too, not least the naval dockyards.

Journeying to Portsmouth or Plymouth, the drovers would certainly have received a warm welcome at Stockbridge, with offers of ‘Gwair tymherus porfa flasus cwrw da a gwal cycurus’ (worthwhile grass, pleasant pasture, good beer and comfortable shelter) still visible on a thatched cottage in the Hampshire town. The more enterprising farmers would not have needed the mural’s rather idiosyncratic Welsh, having taught themselves English, all the better to barter at market and along the way, given the cost of such a journey.

An old toll house, now at the National Museum of Wales in St Fagans, but originally situated outside Aberystwyth, listed that ‘for every drove of Oxen, Cows, or Neat Cattle, the sum of Ten Pence per Score’ was charged, ‘and so in proportion for any greater or less number’. A drove of ‘Calves, Hogs, Sheeps, or Lambs’ might have cost only half the amount, but it was only the beginning of a much longer bill. Droving farmer Roderick Roderick travelled as far as Kent in 1838 and had to pay to open gates at Lampeter, his hometown, as well as at Cwmann, Llanfair-ar-y-bryn, Rhydyspence on the border and three further tolls before Hereford, where he was charged yet again. Three more dotted the road to Tewkesbury, ahead of the journey across the Cotswolds. Grass for cows and beer for his colleagues are also noted in the accounts, with three lots of shoes and the price of grazing.

However expensive it was when all the items were totted up, the journey was nonetheless worth it. Such was the high demand for good Welsh Blacks on an Englishman’s roasting plate that, during the early 1800s, a drover-dealer could bring home thousands of pounds. And even if staff accompanying someone else’s livestock banked a mere three shillings a day, plus a bonus when the cattle were sold, the system provided ready employment during the ‘hungry gap’ and after harvest, offering greater rewards than staying at home.

The benefits of these journeys were as much systemic as they were seasonal. As well as ploughing essential routes through the landscape, drovers founded banks. The continual presence of highwaymen and other bandits meant it frequently wasn’t safe to carry cash, so farmers took credit notes with them. Sometimes, despite formal licences and ‘certificates of respectability’, it meant a visiting Welshman was considered unscrupulous, like the land pirates themselves, although the scheme also saw the creation of the aptly named Black Ox Bank in Llandovery in 1799.

The branch has since gone, like so many other rural banks. Vanished, too, are some of the schools founded by drovers, including at Pumpsaint and Ffaldybrenin, where a resident farmer’s understanding of English was a boon for locals. But, if recent changes have forced the closure of these droving bequests, the entire tradition was terminated by the advent of the railways — at least until a 1911 rail strike saw a brief return to old ways. Nonetheless, vestiges of the droving life remain.

Whenever you turn down a country lane, see an old forge, visit a remote pub or take a breather beneath a cluster of pines, you are likely treading in the footsteps of those formidable farmers, their cows and their sheep. Yet it was, in fact, the drover’s canine companions who proved toughest of all. Having reached the market, they simply turned on their paws and ran. Returning to Wales by means of their nose alone, they would be found slumped by the hearth, days before the master stepped through the farmhouse door.

Gavin Plumley is the author of ‘A Home for All Seasons’ (£16.99, Atlantic Books), out now in hardback and as an audiobook

Credit: Pythouse Kitchen Garden

Pythouse Kitchen Garden: An ideal spot to reward yourself after battling past Stonehenge on the A303

After one too many sub-standard service station sandwiches, Rosie Paterson finds the Pythouse Kitchen Garden, a spot just off the

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Mary Greene

-

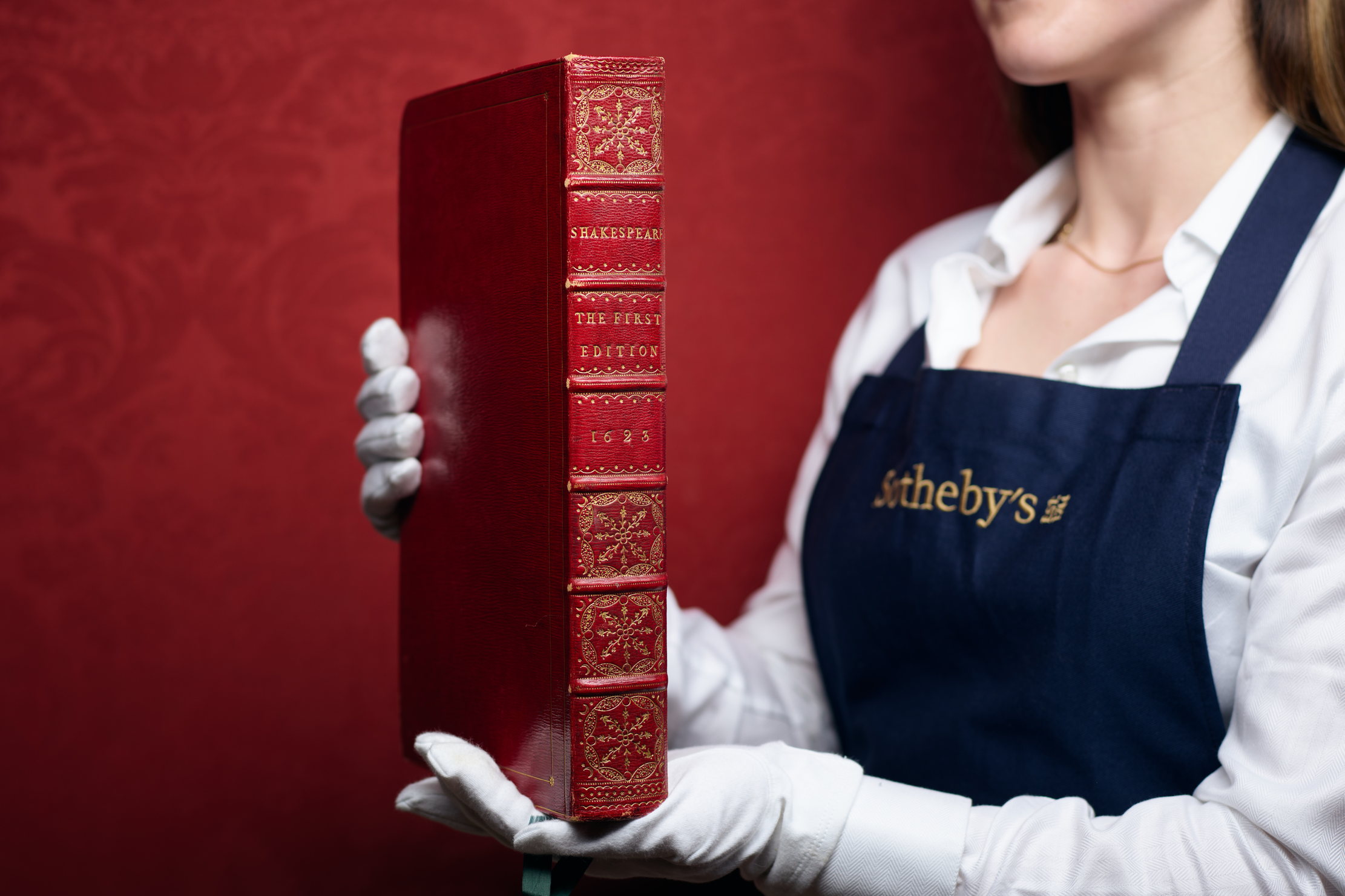

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle