Curious Questions: Is the chocolate side really the top of a Jaffa Cake?

Martin Fone discovers nothing is quite as it seems in the world of Jaffa Cakes — including whether they are a biscuit or a cake or whether chocolate sits at the top.

In these grim and unsettling times, a temptation few of us can resist is to seek comfort in a warming beverage and a few biscuits. It is remarkable how often such a simple pleasure can put a smile back on our face.

According to a report in Grocer magazine last October, biscuit sales in the United Kingdom had increased by £160.8m over the last twelve months, a year-on-year increase of 5.5% or, to put it another way, an extra 144 million packets purchased.

Lines that have done particularly well include chocolate biscuit bars, custard creams, digestives (plain, but especially chocolate) and Jaffa Cakes. Conversely, biscuits which were marketed as healthy and natural had seen a chunk taken out of their market share.

Although I am normally a fan of the chocolate and orange flavour combination, I have never really taken to the Jaffa Cake.

Circular in shape, 2⅛ inches in diameter and consisting of a layer of Genoise sponge, a layer of orange-flavoured jam and a coating of chocolate, they were first produced by McVitie and Price in 1927 in their Edinburgh premises.

These days McVitie’s entire output is made south of the border, in its factory in Stockport on a production line a mile long. They are now firmly established as one of the nation’s favourite confections, regularly appearing in the top five of polls seeking to cast a weather eye on our taste in biscuits.

As McVitie’s never trademarked the name Jaffa Cake, the door was opened for other manufacturers and supermarkets to make similar products bearing the same name, an invitation they were only too willing to accept.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Elsewhere, in the United States Pim’s Orange is marketed as a ‘European biscuit’ with a soft sponge but a thinner, snappier chocolate coating.

German manufacturer Bahlsen incited the ire of the British tabloids by launching an oblong version in 2009. They claimed that the shape made it easier to pack and dunk and its extended jam layer made the cake moister.

The name Jaffa refers to a variety of orange associated with the region around the Israeli port, but, curiously, the sealed layer of jam in the middle is made from apricot, sugar, and tangerine oil.

McVitie’s website does point out, though, that the oranges are used to flavour the cake.

I now understand why I am not a Jaffanatic. The only foodstuff that I cannot abide is the apricot, an aversion I put down to the amount of the stewed fruit I was force-fed as a baby.

Nothing is quite as it seems in Jaffa world, not least whether it is a cake or a biscuit.

This may seem rather a moot point, but the byzantine nature of our tax laws is meat and drink for clever lawyers and accountants. While the name Jaffa Cake trips off the tongue rather easily, whereas Jaffa Biscuit is a bit of a mouthful, this may just be because we are accustomed to that formulation.

When it comes to the application of Value Added Tax (VAT), though, the distinction between the two is all-important, cakes being zero-rated and biscuits standard rated.

When VAT was introduced into the UK in 1973 as a condition of our entry into the European Economic Community, Jaffa Cakes were regarded as cakes.

Customs and Excise decided to revisit that decision on the grounds that they were packaged and marketed like biscuits and generally found on biscuit counters. McVities dug their heels in and the matter went to court.

In arriving at his decision on August 21, 1991, Mr D C Potter QC acknowledged the difficulties in resolving the case.

Linguistically, there was no clear demarcation between ‘cake’ and ‘biscuit’ and, as such, ‘a product which is a biscuit (whether or not covered in chocolate) is capable of being also a cake’.

Manfully, he waded through the morass of evidence and linguistic niceties and found in favour of McVities. For the purposes of taxation, Jaffa Cakes were cakes and zero-rated and remain so to this day.

What proved decisive was the fact that they looked and behaved like a cake. The egg, flour, and sugar ingredients, which, when kneaded together and then aerated made up the sponge part, were identical to those used to make a traditional sponge cake.

The sponge-cake part of a Jaffa Cake, Potter concluded, was in itself ‘cake’. He also noted that the sponge-cake part was a substantial part of the product, not in flavour, but in bulk and texture when eaten.

That Jaffa Cakes were soft in texture and easily crumbled, not hard and needing to be broken or snapped as biscuits are, made them seem to resemble cakes, as did their inherent moistness.

Their propensity over time was to become stale, and then crisp and hard, in line with other sorts of cake and unlike a biscuit which tends to go soft with age.

It was this moisture point that also resonated with the Irish Revenue Commissioners, who, noting that its moisture content was greater than 12%, declared the Jaffa Cake to be a cake and, as such, would attract the tax rate (lower, of course) associated with a cake.

So, a cake it is, but which is the top and which is the bottom? A storm in a teacup boiled up in social media circles in late 2020 over this seemingly innocuous and rather obvious question.

McVitie’s own website shows it with the chocolate layer uppermost and, rather like an iced cake, the natural inclination is to hold it that way so that when you sink your teeth into the delicacy you get the comforting taste of the chocolate first, followed by the jelly, and then the sponge. However, a representative of Jaffa Cakes responded to the online controversy by saying that ‘our Jaffa Cakes go through a reservoir of chocolate, so the chocolate is at the bottom’.

This line was reiterated in a later response on Twitter. Of course, there may be a simple explanation to this confusion.

In the manufacturing process, the cake is positioned in such a way that chocolate is placed at the bottom. That does not necessarily mean that when the product is consumed, it should be held with the chocolate at the bottom. Social media storms often appear to be much ado about nothing.

There is much about a Jaffa Cake for the aspiring lawyer, etymologist, and philosopher to get their teeth into.

Most of us, though, are just content to enjoy its succulent flavours and some find them irresistible. Take the case of the burglar who, on breaking into a property in Birmingham in July 2012, could not resist the siren call of a packet of Jaffa Cakes he had spotted lying around.

In his fervour to get at them, he left a clear set of fingerprints on the box, evidence enough to reward him with a substantial custodial sentence. The power of the Jaffa Cake is formidable.

Curious Questions: Do love potions actually work?

The idea of a potion that can make someone fall in love is as old as the idea of love

Curious Questions: How does soap work?

We've been using soap for thousands of years, as Martin Fone finds out. But how does it actually work?

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa Harrison

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa HarrisonThe novelist, children's author and nature writer Melissa Harrison joins the podcast to talk about her love of the natural world and her new app, Encounter.

By James Fisher

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we carve pumpkins at Halloween?

Curious Questions: Why do we carve pumpkins at Halloween?The devilishly smiling image of Jack O'Lantern is inseparable from Halloween, but what's the story behind it? Martin Fone explains — and discovers that the festival many complain about as an American import has been this side of the Atlantic for centuries.

By Martin Fone

-

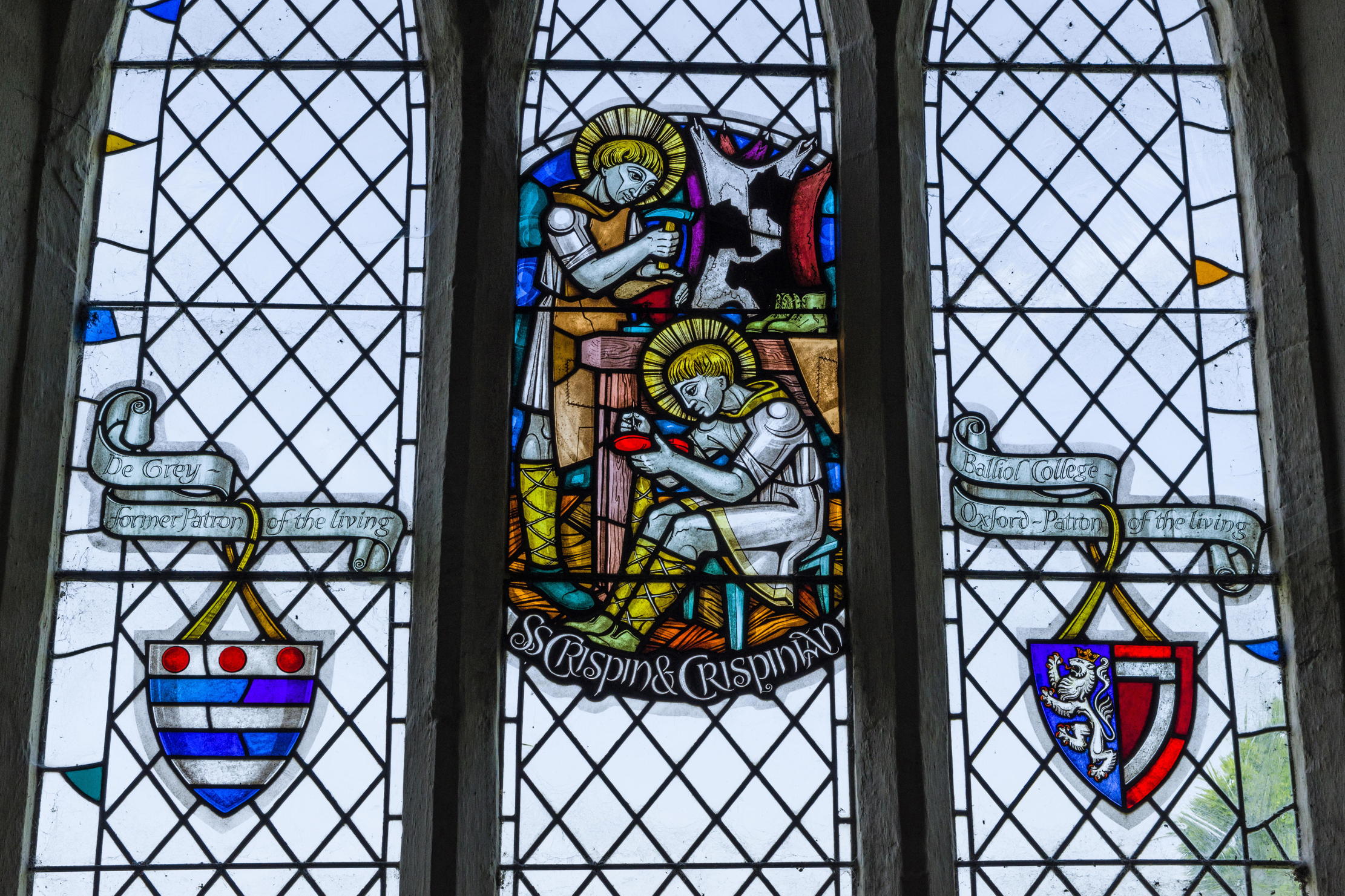

Who was the real St Crispin, and what did he have to do with the Battle of Agincourt?

Who was the real St Crispin, and what did he have to do with the Battle of Agincourt?You have questions about Shakespeare's most famous speech. We have answers.

By Ian Morton

-

Do you know your apple-catchers from your tittamatorter? Take a crash course in the UK's local languages

Do you know your apple-catchers from your tittamatorter? Take a crash course in the UK's local languagesWith experts warning that regional accents could disappear within decades, our sometimes quaint and, often, bizarre dialect words are becoming ever-more precious.

By Victoria Marston

-

Curious Questions: Why do barristers and judges wear wigs?

Curious Questions: Why do barristers and judges wear wigs?Like marmalade on toast, saying sorry and the Shipping Forecast, there are few things more typically British than the courtroom wig. Agnes Stamp explains why our barristers and judges wear them.

By Agnes Stamp

-

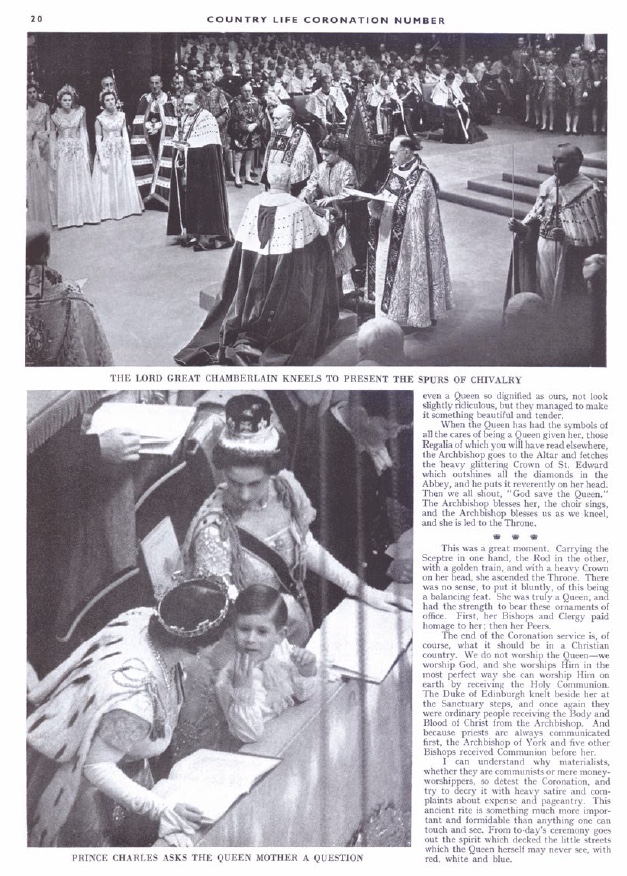

What it's like to have a prime seat at a Royal Coronation by John Betjeman, who reported for Country Life in 1953

What it's like to have a prime seat at a Royal Coronation by John Betjeman, who reported for Country Life in 1953The late, great Poet Laureate John Betjeman was among the congregation when Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was crowned in 1953 — and he wrote about it for Country Life. We're very proud to reproduce that article now — The Queen's Coronation: In The Abbey by John Betjeman.

By John Betjeman

-

Curious questions: Did the modern Olympics really start in Much Wenlock?

Curious questions: Did the modern Olympics really start in Much Wenlock?Martin Fone traces the history of the Olympics and examines the contribution of Shropshire doctor William Penny Brookes.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What was the first ever televised sporting event?

Curious Questions: What was the first ever televised sporting event?Over 20 million people have been tuning in to watch England's stirring exploits at Euro 2020, and the huge numbers look only set to get bigger as the summer goes on. It's a far cry from the first ever televised sporting event, almost a century earlier, as Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Question: When was the first census held?

Curious Question: When was the first census held?As the UK prepares to compile this decade's census, Martin Fone retraces its history.

By Martin Fone