Woodhall Park, Hertfordshire: An exemplary example of restoration that highlights the importance of colour in Georgian interiors

The recent restoration of Woodhall Park underlines the striking importance of colour in our understanding of Georgian interiors, as John Martin Robinson explains.

Woodhall Park was the creation of two notorious Indian nabobs, Sir Thomas Rumbold (d.1791) and Paul Benfield (1742–1810). Both men grew exceedingly and rapidly rich in the 1760s, after Col Robert Clive’s victory at Plassey in 1757, partly through financial dealings with England’s ally the Nawab of the Carnatic. Both nabobs returned to England to invest their new fortunes in a country estate and gain political influence through the purchase of parliamentary seats. They were also both the object of virulent rhetorical attacks by Edmund Burke.

Rumbold entered the military service of the East India Company and was an aide de camp to Clive at Plessey. He returned to England a wealthy man and commissioned Thomas Leverton (1743–1824), a contemporary of the more familiar Robert Adam or James Wyatt, to build the present house (to replace a Tudor house owned by the Boteler family and burnt down in 1771). The two men had met through City connections: Leverton was Surveyor to the Phoenix Fire Insurance Company and the Grocers’ Livery Company.

Leverton’s design for the house was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1777, the same year that Rumbold secured – after a previous attempt – the governorship of Madras. On his departure in December, Rumbold delegated the execution of the scheme to his attorneys, allocating £14,155 for the contract and leaving them power to make design variations. While in India, he was involved in the running hostilities with the French in Pondicherry and was created a baronet in 1779. Payments to Leverton are recorded in Rumbold’s account at Goslings Bank (now part of Barclays).

Sir Thomas returned to England and a storm of criticism. Work to the house seems to have continued unabated, however, and a print room was hung in 1782, proof that the building was structurally complete by this time. Leverton’s plans were published in New Vitruvius Britannicus I (1810) as plates 27 and 28. The major change in execution was the substitution of a twinned imperial staircase with a single flight.

The pleasure grounds and walled garden round the house were laid out by William Malcolm and Son, Stockwell nurserymen and landscape designers, in 1782–83. Later, Joseph Paxton undertook an apprenticeship in the walled garden.

Having fallen out with his eldest son, Sir Thomas directed in his will that Woodhall should be sold for the benefit of the children of his second marriage. The estate, house and contents were acquired for £125,000 in 1794 by Benfield, nicknamed Count Roupee, on his return to England from Madras. Benfield was the son of a carpenter and twice dismissed from the East India Company service for speculation. He immediately set about the substantial enlargement of the property.

Benfield doubled the height of the linking wings, which, in Leverton’s design, had been little more than screen walls for service courts. More information is supplied by the 1801 sales particulars, which described the accommodation in detail. The updated north wing comprised a ‘capital library’ and new dining room replacing Leverton’s in the central block (which was later converted to a music room). The south wing contained additional service accommodation and, upstairs, additional bed and dressing rooms were provided.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The architect is not known, but it might conceivably have been Leverton, who died in 1824. Whatever the case, the new work complemented the old. Most of the interiors are decorated with simple Regency cornices and ceiling roses. There are also some playful Gothic bedrooms.

The exterior of both the Rumbold house and Benfield’s additions is beautifully executed in white brick with refined Classical mouldings of Portland stone. The west front is adorned with Coade stone plaques and served as the entrance front, but a well-proportioned, single-storeyed portico was added to the east of the house later.

Benfield was not to enjoy his new seat for long. In London, he set up a bank in 1793 with a speculator called Walter Boyd, an obscure Scotsman. They went spectacularly bankrupt in 1799. Benfield fled to the Continent and a twilight of poverty. Woodhall was seized by the government on behalf of the creditors and sold – after one failed attempt – in 1801 to Samuel Smith, scion of a much more securely based English banking dynasty.

William Wilberforce, a relation of the Smiths, drew a religious moral from the tale of the two nabobs: Rumbold ‘fresh from India and dripping with gold’ building ‘a magnificent habitation’, but dying after disinheriting his eldest son and Benfield ‘adding a magnificent wing’, but doomed to poverty and exile. He quoted Juvenal’s 10th Satire about the pointlessness of Alexander the Great’s ambition.

In the sales particulars of 1801, the central downstairs room to the north is described as the ‘Etruscan Saloon’; it now became the entrance hall (although it has kept its name). Another change was the restoration to use of Leverton’s dining room and the conversion of Benfield’s in the north wing to a billiard room.

On the whole, the Georgian character of the house was carefully preserved throughout the 19th century, with only minor changes and redecoration. In 1833–34, the deer park was extended, the park wall built and the Loudonesque Hertford Lodge erected. A formal garden with balustrade terraces, restored in 2016, was made on the west front around the same time to place greensward and a sunken ha-ha. Inside, central heating was introduced and a brass floor grille at the foot of the back stairs is engraved ‘Methleys Patent 51 Frith St, 1833’.

The next phase, in about 1860, included the addition of characteristic Victorian gilt Rococo decorations to the drawing-room ceiling. That room still retains its magnificent sculpted white statuary marble chimneypiece described in detail in the 1801 particulars. It is possibly by John Flaxman, who is known to have worked for Leverton as a young man, or John Bacon, who made Rumbold’s monument in Watton church.

Other tactful interventions were also probably made in the 1860s. For example, recent paint analysis by Cathy Hassall has shown that the panels on the staircase walls were originally blank, yet now they incorporate grisailles of the Four Seasons in the style of Biagio Rebecca (who was almost certainly responsible for the Etruscan decoration in the entrance hall). It is possible, therefore, that they were moved to their present position in the 1860s from elsewhere in the building.

The lunettes higher up are filled with paintings on canvas of the four continents and their trade by an unidentified Victorian artist.

When last covered in two articles in Country Life (January–February 1925), the house retained contents that had been transferred at the Rumbold and Benfield sales. Sir Hugh Roberts has discovered that much of this was supplied by the leading London neo-Classical furniture makers Ince and Mayhew. Sadly, the furniture was dispersed after the death of Col Abel H. Smith in 1931, when the family moved out and the house was let to Heath Mount School.

By this time, the house was already considered to be too large, ‘inconvenient… and uncomfortable for modern conditions’, according to Avray Tipping in Country Life. He described Woodhall as an exemplum of how a great country house could be adapted for modern use, not by drastic changes, but by restricting ‘the habitually occupied area’. He suggested closing the basement, north wing, big drawing and dining rooms, and bringing the kitchen up to the ground floor adjacent to the Print Room in the south wing, which could be used as the dining room. This sensible formula foreshadowed the domestic adaptation of many English country houses after the Second World War.

The present owners, Ralph and Alexandra Abel Smith, live in the 18th-century stables (on the site of the Tudor house that pre-dated the house). These were converted by the late Thomas and Alma Abel Smith into a residence in the 1950s by Darcy Braddell, an architect recommended to them by Christopher Hussey of Country Life.

Mr Abel Smith has replanted the park to a landscape plan prepared by John Phibbs in 1984. He and his wife have also worked to restore some of the most important interiors of the house. The three main rooms – the Print Room, the Etruscan hall and staircase hall – were restored in the 1960s with grants from the Historic Buildings Council. In the more recent restoration work, undertaken since 1995 in association with English Heritage, there is apparent the more scholarly and scientific approach to interior restoration that emerged in the late 20th century following the restoration of Spencer House, Uppark and Windsor Castle.

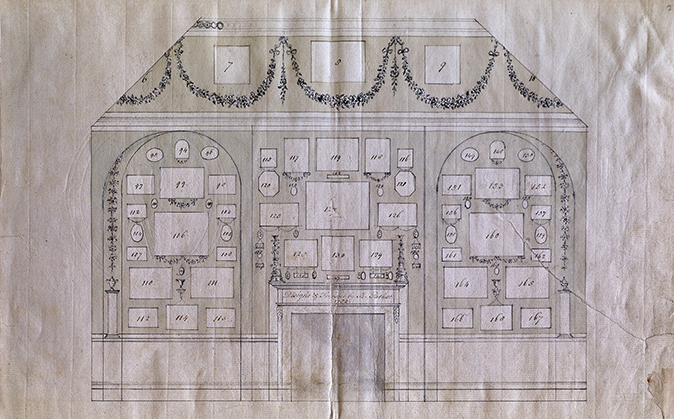

The first room they addressed was the Print Room. It is lined with 350 engravings framed with garlands and festoons, the pictures forming ‘a complete digest of the connoisseurship of the time’, a microcosm of English Grand Tour taste, as described by Francis Russell (Country Life, October 6, 1977). The conservation work was done by Allyson McDermott, the paper and wallpaper expert.

All the prints were taken off and cleaned and remounted on Japanese lining paper and the original ground paper colour of verditer blue was reinstated. Ink and wash plans for the design survive, together with an accompanying book identifying all the subjects. This also names the obscure creator of the room, R. Parker, and the date 1782.

The next phase of work revived the Staircase Hall, a magnificent full-height central space. The repairs have been done in two stages supervised by the conservation architect Peter Scott, recommended by Sir Hugh Roberts. He had previously worked on the restoration of Clarence House and the Chapel Royal at St James’s Palace. The first job was the repair of the rare wrought-iron structure and re-glazing of Leverton’s domed skylight in 2008.

The second, carried out in 2011–12, was the complete reinstatement of the spectacular original colour scheme in shades of lavender and grey, with the staircase balustrade in white and gold, following research by Mrs Hassall. In the 19th century, the walls had been painted pale blue and the balustrade black, so the transformation is dramatic.

The results reveal the staircase hall as one of the most impressive English neo-Classical interiors, the careful colour harmonies bringing out the full impact of the delicate stucco decoration, which was almost certainly executed by Joseph Rose.

Conservation work has also been carried out in the entrance hall, with consolidation, repair of the Bossi chimneypiece and cleaning of the paintwork and the Classical roundels on canvas glued to the walls. The painted decoration is based on Hamilton’s Vases and the subject of the Classical roundels is the story of Cupid and Psyche.

Mrs Hassall’s research showed that the extant scheme is a mid-19th-century renewal of the original Leverton colours, repeating the 18th-century grey-blue background for the walls and a similar Etruscan palette of browns, reds and ochres for the ceiling.

All this restoration work has been made possible by the success of the wider Woodhall estate and its commercial enterprises, including forestry, farming and commercial and residential lettings. It also forms just part of the conservation objectives overseen by the present owners, which have included the planting of 40,000 trees and many miles of hedges. The continuing success of the estate will hopefully allow the restoration of the house to continue.

The magnificent puzzle of Crichel, one of Dorset’s grandest Georgian houses

John Martin Robinson is your guide to a place where peeling away one layer only ever seems to reveal several

Credit: Will Pryce

Powderham: The Devonshire castle that's been in the same family for 600 years

An ancestral West Country home that has passed through the hands of one family for the past 600 years has,

Wells Cathedral, Somerset: A symphony of architecture

In the first of two articles, John Goodall describes the architectural development of Wells and the struggle of its late-medieval

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.