Willards Farm: A spectacular reimagination in the spirit of Lutyens and the Arts-and-Crafts Movement

The imaginative extension of a farmhouse in the spirit of Lutyens and the Arts-and-Crafts Movement has created a delightful and humane family home, Jeremy Musson reports. hotographs by Paul Highnam.

The older farmhouses scattered across rural, deeply wooded areas on the Surrey and Sussex border have lost nothing of their appeal in the 21st century. Willards Farm, near Dunsfold, has recently been subject to sympathetic renovation and substantial extension. At its core, the house is a four-bay, 16th-century timber-frame house of two storeys, under a clay-tile roof, with a substantial off-centre chimney stack. It occupies an elevated site and was extended to its northern end in the 1930s and to the south in the 1980s. The latest works, completed in 2019, were imaginatively designed by architect Stuart Martin for a young family.

These new additions celebrate the famous domestic vernacular tradition of this district in two different ways. Firstly, the timber-frame original has been sensitively renovated and enhanced; secondly, new reception rooms and accommodation have been created to the north and west, representing an artistic response to the traditional vernacular of timber, brick, clay tile and modelled forms. At the clients’ request, local people were used wherever possible in the construction work; the principal contractors, Brickfield Construction, are from nearby Fernhurst and many of the craftspeople employed on the interiors come from the area.

Mr Martin studied architecture at the University of Nottingham and first worked for conservation specialist Jeremy Benson (1925–99) of Benson and Bryant, a leading figure in the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB). Mr Martin founded his award-winning practice, based near Evershot in Dorset, in 1996, and has made a name for himself creating well-designed houses in both the Classical and vernacular traditions. Chitcombe House, Dorset, a country house designed by him (Country Life, September 6, 2017), exemplifies an imaginative response to both the Classical tradition and the courtyard form.

Mr Martin is also on the architectural advisory panel of The Lutyens Trust, which promotes research and understanding into the work of Sir Edwin Lutyens. It is not difficult to see the work at Willards as a 21st-century response to the great architect’s work, which is unsurprising, as Lutyens grew up in the area, gaining inspiration from these kinds of farmhouse and barn groups. The new work at Willards is both a reflection and a concentration of the house’s original character. It remains a picturesque house of Surrey vernacular charm — framed by oaks and the typical rolling wooded landscape of this area — but with a memorable new dimension.

It is also still intimate and comfortable. In this, it may be compared to nearby Vann, the country retreat created by W. D. Caröe for himself and his family. Built in 1906–08 around a mid-16th-century manor house with an addition of about 1700, this work preceded Lutyens’s better-known merging of additional ranges into older buildings to form a new-old house, such as Great Dixter in East Sussex. Mr Martin visited Vann when he was preparing the designs for Willards.

The interiors of the new parts at Willards are enriched with details that were specially commissioned by the owners for the house, including wood carving, letter-cut inscriptions and stained glass. But this is also a house shaped by the advantages of technology and informed by an awareness of the importance of sustainability. Multiple buildings — and a pool — on the site are heated by a ground-source heat pump, and there is solar panelling on the farm.

The brief from the owners was principally to extend the accommodation of the older house to make it more convenient for modern family life and to add a spacious new music room suitable for a full-size grand piano — in essence, to provide extra space without losing any of the character of the 16th-century core. The 1980s additions at the south end of the house were removed, so that the older house could be more clearly read, and a new pergola and summerhouse, both designed by Mr Martin, added to the garden at this end. The modest 1930s addition to the north end was replaced with a substantially larger new range that was carefully integrated into the existing house, so as to remain distinct, but entirely in harmony. Also at the north end, the formation of new courtyards and enclosures add interest to the design.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Every effort was made to retain the 16th-century character of main house, especially as seen on the approach. This was an exercise in realising the aesthetic value of the composition, making use of the timber-frame barn, running east from the north end of the house, to frame the small former farmyard, together with a later outbuilding (now a cottage). Both have been restored and the area in front of the east entrance of the house, now partly enclosed by the barns and a large pond, has been put to lawn.

The end of the drive turns away to deliver visitors to the north end and, by this means, cars are removed from the front and the unimpeded lawn gives the original house its proper visual context. The weather-boarded barn has been made suitable for hosting concerts, recitals and practice sessions and is used by the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment for performances and filming.

The new entrance court created beyond the barn to the north is a deft piece of domestic work that comes as something of a surprise when first seen, yet also fits in well with the original grouping. It has a distinctive, half-hipped roof, a cluster of dormers also capped in clay tile and a quirky, ground-floor corner bay window to one side. The whole fits together quite naturally in the manner of a farmstead, with the different elements drawing the eye from side to side.

An open loggia provides a practical, but welcoming everyday approach to the north end of Willards. This is supported inside by all the useful rooms and places for boot and coats associated with family life in the country. This semi-formal entrance yard is also framed to the north by a new 1½-storey building, a small, oak-boarded, poolside guest cottage with dormers. Replacing a 1980s garage block, this was built before the other extensions and the family lived here during the main works to the house.

The brick walls enclosing the pool house create the impression of a traditional farmstead enclosure and the tiled coping echoes the treatment of a Lutyens pergola at Pasture Wood, Dorking, of about 1912. One angle of the walls is resolved with a fine dovecote and ceramic decoration of the pool by Craig Bragdy means that it resembles an ornamental pond.

The dynamic quality of the new addition, enlivened by new brick chimneys and dormers, is especially revealed on the west side. Here, the surprising harmony of ancient and modern is underlined by the unifying presence of the new pitched roof maintaining the same line as the historic roof. The overall character of these additions is taken from the organic form of an old barn in the nearby parish of Chiddingfold and, viewing it from this side, you realise what a bold addition it is, but also how the confidence of the design carries the whole, together with the quality of the traditional materials.

This new range encompasses a large, open-plan kitchen and dining room opening onto a simple oak veranda. The family kitchen, with joinery by Joel Bugg, connects seamlessly through to the principal reception room of the house.

This is the Music Room, formed in large part by a bold Lutyens-like grid of oak-frame windows, lighting the double-height music room within; something that can also be viewed from an open gallery above. This room has — intentionally — something of the character of the famous 1920s Music Room that Lutyens designed for Edward Hudson at Plumpton Place. The lower register of windows in the Music Room at Willards is plate glass, facing the fine view, whereas the upper registers are leaded windows, echoing those of the old house.

The fine limestone chimneypiece in this room was carved by the Cardozo Kindersley workshop in Cambridge run by Lida Kindersley. It bears a line of verse from John Muir — ‘in every walk in nature one receives far more than one seeks’ — and the border is enlivened with small relief carvings of flora and fauna seen on the land around the house, including an owl, wren and frog. These are intended partly to intrigue, but also to engender interest and respect for Nature in the heart of the house.

This chimneypiece marks the place where the historic part of the house meets the new part. In many ways, this marks a turning point for the property, which is why it has been marked so carefully and deliberately. The gallery over the chimney-piece connects directly to the new oak staircase of a 17th-century character, made from oak with turned balusters. The fine oak-leaf carvings on the newels are by Graham Heeley of Itchingfield, West Sussex. Reflecting local Nature, there are some internal stained-glass windows by Rachel Mulligan. Bedrooms in the new range are generous, but designed to echo the same spirit as those in the 16th-century house; the barrel-vaulted bedroom corridor of the new range, in particular, is an original response to that of the old house, which was cut through the bracing of the timber framing at some point. Panelling and interior timber structure is all limed to great effect and ingenious window seats and fitted beds complete the picture.

Mr Martin and his clients, who managed the project of Willards closely themselves, have been particularly keen to celebrate the use of traditional, largely natural materials in a structure that can evolve and be adapted in the future, with particular stress laid on materials that have come to us from pre-industrial culture. Mr Martin feels that older models of vernacular buildings have much to teach us as we wean ourselves off fossil fuels, as well as the importance of our connection to Nature.

The owners have been exemplary in their vision for the house: its character, its details and its use not only as a loved family home, but as a much-appreciated retreat where musicians can practice and perform. Their commissioning of new works by talented craftspeople is an especially memorable feature, not only in its celebration of skills, but in its homage to Nature and landscape. The build itself was tightly planned, but ‘very happy, and successful’. Mr Martin has become a close friend of the owners and they are working on several other projects together. Many of the contractors and craftspeople who met on this project have also gone on to work together elsewhere.

Mr Martin designed the garden layout for Willards. He is highly conscious of the tradition of ‘framing the spaces’, which Lutyens and Jekyll developed in the 1890s and early 1900s. It is by these means that this old house has become a place memorably humane, friendly and vibrant, with traditional and modern design values blended fast together.

-

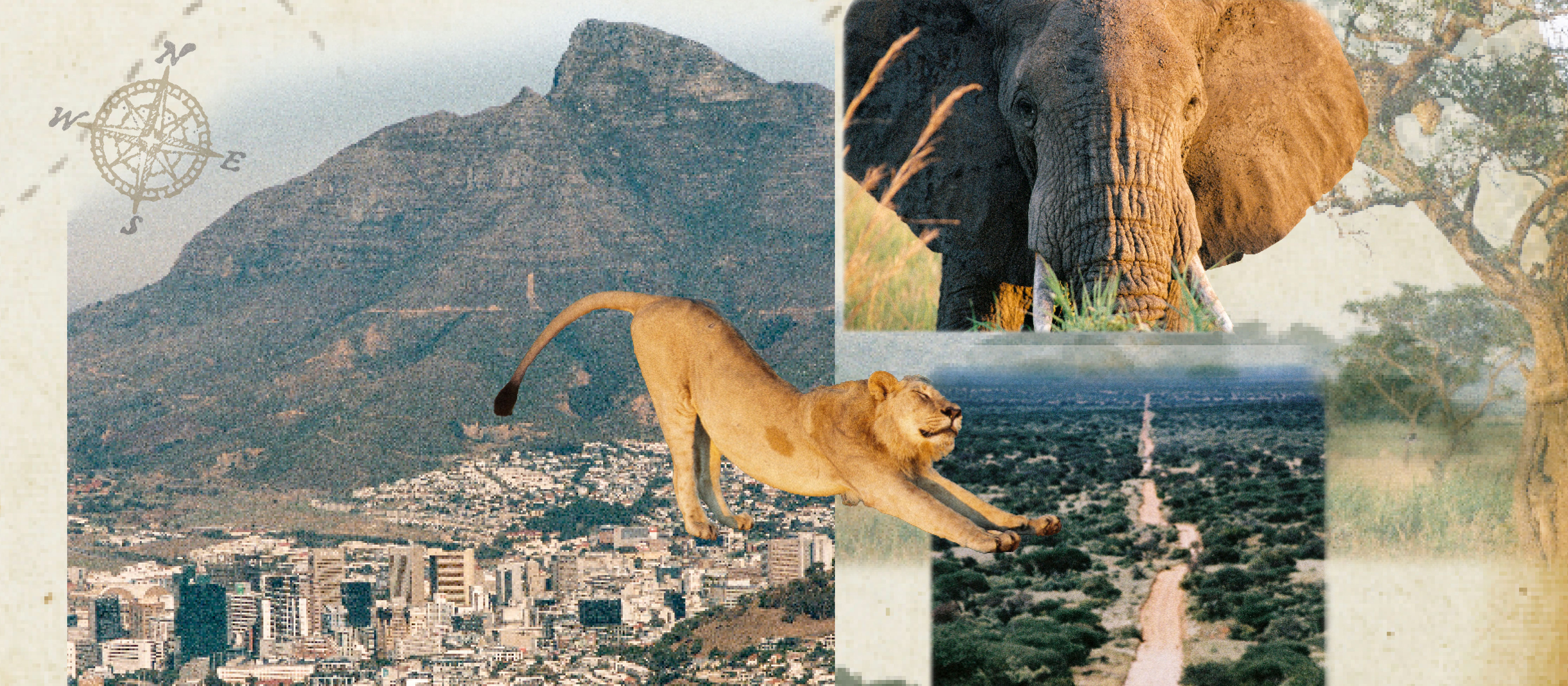

Vertigo at Victoria Falls, a sunset surrounded by lions and swimming in the Nile: A journey from Cape Town to Cairo

Vertigo at Victoria Falls, a sunset surrounded by lions and swimming in the Nile: A journey from Cape Town to CairoWhy do we travel and who inspires us to do so? Chris Wallace went in search of answers on his own epic journey the length of Africa.

By Christopher Wallace

-

A gorgeous Scottish cottage with contemporary interiors on the bonny banks of the River Tay

A gorgeous Scottish cottage with contemporary interiors on the bonny banks of the River TayCarnliath on the edge of Strathtay is a delightful family home set in sensational scenery.

By James Fisher