Why and how our local churches should live on for the benefit of us all in a secular age

Parish churches may still be physically the centre of communities, but their redundancy as places of worship is becoming a national crisis. Simon Jenkins proffers solutions to the nation’s greatest conservation challenge, including deconsecration and looking to European models.

Thousands of England’s most ancient and prominent historic buildings are now standing empty and unused all or almost all of the time. By law, they cannot be demolished, nor do most people want them demolished. Redundant churches are by far the nation’s greatest conservation challenge. They form the visual focus to almost every English village and town, high street and market place. Their towers are the signatures in the surrounding countryside. They are infinitely precious.

Fewer than half of Britons now call themselves Christian of any denomination, with only 12% professing loyalty to the Church of England, a fall from 40% in 1983. More critical is that few even of these members are going to church. Church House statistics show regular church attendance at barely 2% of the community or well under a million people, a decline of some 30% since the turn of the 21st century. Early indications show the pandemic may have led to a further 20% fall — more people in England worship regularly in mosques than in parish churches.

The implication of this decline in church-building use cannot be ignored. The Inge report in 2015 estimated that some 2,000 churches had fewer than 10 regular or occasional worshippers. This number has reportedly doubled. Of Lincolnshire’s 615 churches, 174 are apparently used only as occasional ‘festival churches’. An extraordinary 900 churches are on Historic England’s Heritage at Risk register, their custodianship an ever more severe strain on overstretched clergy. Of those still in use, thousands need support from outside their parish in addition to paying for their clergy. Their upkeep can be crippling, repairs requiring urgent fundraising. The average cost of repair was put by Inge at £10,000 a year, this in addition to the ‘parish share’ churches must pay for clergy salaries and diocesan expenses.

Two conclusions are clear. One, a new regime must urgently be found for the guardianship of these structures. The other is that their present custodian, the Church of England, cannot undertake this task, aided or unaided. In other words, redundant churches present a secular crisis demanding a national response.

Parish churches were and are quintessentially local institutions. They were built, maintained and used by their parishes, tied to a pattern of rectories, manors and parochial councils. From the Church’s point of view, where such parishes are now redundant they can be merged with their neighbours and clerical duties shared. Their buildings, however, are static, local museums and places of record, shrines of ceremony, celebration and memorial. That is why a National Churches Trust survey indicates that some three-quarters of the public values a church’s presence in the community and does not want it to disappear.

This situation is not unique to England or even Britain. The 2019 Pew report on European churches found attendance everywhere in decline. To the ecclesiastical sociologist Grace Davie, a church is perceived as a sort of public utility, a resort in time of emergency and performing an invaluable social service. Church-going has mutated from being ‘a culture of obligation and duty to a culture of consumption and choice’. The task for those seeking a future for redundant churches is to harness that sense of local identity and public utility. There is no alternative to reuse.

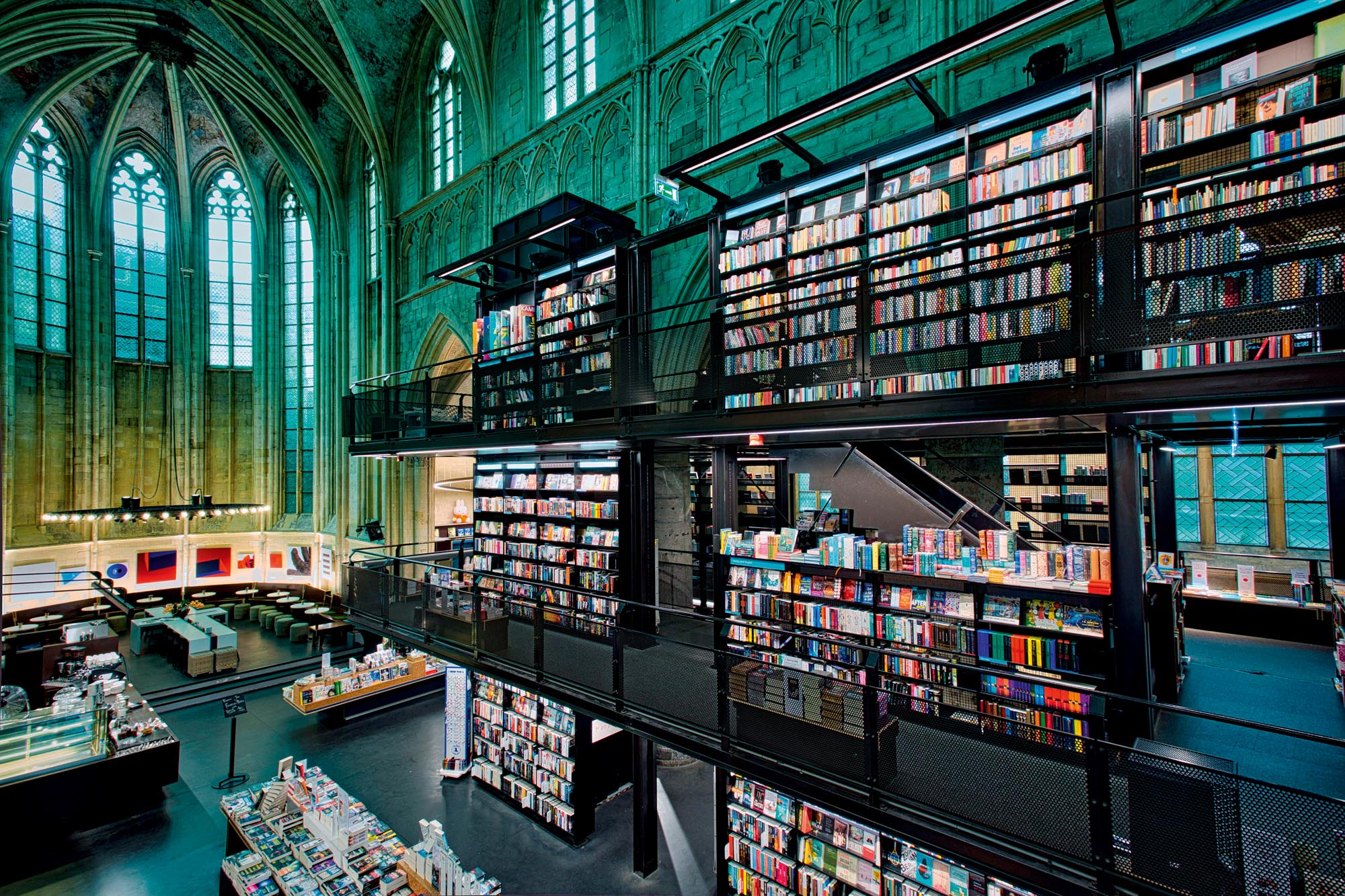

Elsewhere, enterprising initiatives — including in churches still in use — have yielded ingenious new uses. The urbanist Ray Oldenburg has argued we have a need for gathering spaces other than those of home and work, what he calls ‘third places’. Churches are ideally suited as such. I have come across them as concert halls, rock venues, theatres, art galleries, post offices, libraries and bookshops, antique stalls, nursery schools, climbing walls, youth clubs, yoga classes, meditation centres, coffee bars, pubs and even a brewery. I am told that there are now more food banks in churches than there are McDonalds in high streets.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

These examples show that modern communities, especially rural ones, have needs to which churches can offer answers. Now that developer pressure has all but dismantled British town and country planning, village and town centres are being denuded of high streets. They are losing shops, nurseries and personal services. More than 2,000 pubs have closed since 2017, not necessarily because they were unviable, but because their ‘use class’ was no longer protected and their sites were more valuable as houses. The ‘congregational’ in England has been surrendered to the private.

Most English people still claim to ‘live in a village really’ or, if not, would like to do so. Yet planning no longer safeguards the buildings on which village identity depends. Churches, if only by being undemolishable, are well placed to safeguard this identity. Most are located at the hub of their community. They are large, recognisable and spacious. Deconsecrated, there need be no constraint on their use, although new uses should retain public access and churchyards should remain natural enclaves.

Repurposing a church building is clearly difficult. It has been designed and fitted for a specific ritual and is rarely convenient for alternative uses. A large space needs to be heated; there is usually an absence of dividing walls and rarely any plumbing. If churches are to become adaptable, listed-building flexibility and reordering must be accepted. Wonders can happen, however. A church in Bristol is now a circus-training school, another in Ipswich a meditation centre, one in Mayfair a nightclub. I once saw Tamworth church, still in use for worship, with its west doors thrown open to stalls from the adjacent market. Each was a building reuniting with its community.

Certainly, respect must be sought for the past uses of a church, as in its monuments and memorials. There may be a demand for some consecrated space to be retained. Each church is unique. But every attempt must be made to find a public use before the last recourse, which is conversion to housing. In my experience, the key lies not in a church being in a prosperous or populous place. It lies in a supply of volunteers on whose imagination, enterprise and energy it can call. Rescuing England’s parish churches depends ultimately not on money, but on people.

To whom should these buildings belong? Most people with whom I discuss churches state simply that they are ‘not for me’. This is not only that the church’s story and culture is no longer part of their upbringing. Medieval and Victorian church buildings can seem austere places, gloomy and meaningless. They speak in a language and display an imagery that few Britons any longer understand. This image has to be confronted if these buildings are to become welcoming to new users.

As I believe strongly that churches should stay in the public domain, they should pass into the ownership of a public authority, preferably a local one. It was local people who mostly paid for the erection of churches and it would be best if local people remained responsible for their future.

The answer has to be for the Church of England to pass unused properties to civil parish councils or the equivalent in urban areas, the community, town or city council. Church buildings would be in the same category as a town hall, town museum, market or park. It would be an expression of local pride — or at least a comment on it. In every sense, such ‘localisation’ would recapture the church’s role as a defining local institution, symbolised by communal ownership. Decisions on its use, within the terms of historic-buildings regulation, are for officials answerable to a local electorate.

One thing is essential to make this transfer of responsibility realistic: access to resources. At this point, it is worth examining where identical challenges have arisen elsewhere in Europe. The Pew survey pointed out that Britain is exceptional in making no formal national provision for church support. Nine European governments — in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Italy, Portugal and Spain — all levy a ‘church tax’ on their citizens. Four of these, Italy, Germany, Portugal and Spain, allow objectors to opt out of paying. In France, all churches are state owned, in the care of local parish councils with central support.

In almost all these cases, revenue is collected centrally and distributed to churches through the various denominational organisations. Although the evidence is patchy, figures suggest that opposition to church taxes is small, indeed, majorities even in the ‘voluntary’ countries still opt to pay. England is in a minority of states that have inherited no historical obligation on the public sector to support their churches. This is largely the result of the Church of England’s legacy of great wealth and the assumption that it needs no further support.

The likelihood of any British government introducing a central church tax is minimal. If redundant churches are to be transferred to local councils, it is clear that they must be free to levy their own resources to pay for them, at least unless or until they can support themselves. Local-council taxpayers are already precepted for specific purposes, such as the police or the upkeep of parks and pavilions. To this should be added the local church, perhaps, with an option not to pay. With average maintenance now about £10,000, this need only be minimal, less than £50 a year according to band. If this needs a change in law, then change it.

Such ownership will be a challenge for local councils and there will be many different management models. Although a church may no longer be a place of collective worship, the intention is to restore its role as a place of coming together, of social intercourse. In a sense, this revives some concept of ‘establishment’ for the parish church, local rather than state. It fuses the character and security of a community with its most prominent former institution. True, that institution may no longer be ceremonial or participatory, but it might retain some of that aura as a physical reality.

There will be accidents. Transfer of ownership may not always be straightforward and there will be cases, especially in isolated rural areas, where parish custodianship is unfeasible. As with any historic building, dereliction may require legal intervention, listed-building enforcement and possible disposal and sale. There may be a residual need for some state or charitable fall-back, but always the ambition must be to restore churches to local people.

I repeat that this proposal refers only to churches that are redundant. The number is incalculable, but research suggests it applies to between 2,000 and 4,000 buildings. The reform should revive the image of the church to millions of people and thus mark a new era in the story of local England.

Britain's 100 best Railway Stations: Simon Jenkins on the gateways to our railways

Simon Jenkins: The new British countryside is being not planned, but plonked

Credit: Getty Images

Simon Jenkins: The new planning white paper is a domesday for development

The white paper on planning promises to license untold damage to the British landscape, argues Simon Jenkins.

England’s best view? Tintagel, Cornwall, where seas of turquoise crash on slate tinged with copper

Simon Jenkins chooses Tintagel, Cornwall as one of England’s best views.

Simon Jenkins: Britain’s historic houses are, for the most part, safe — that is not true of the countryside

The National Trust is tying itself in knots, argues its former chairman Simon Jenkins, while missing real challenge of the

Simon Jenkins: Europe's cathedrals are the true wonders of the world, and were once daubed in colour — it's time they were once more

Our cathedrals were once filled with colour, argues Simon Jenkins, and today's monochrome restorations are a historical travesty.

Simon Jenkins is a journalist and author who began his career at Country Life before going on to serve as the political editor of The Economist and editor of The Times.

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill

-

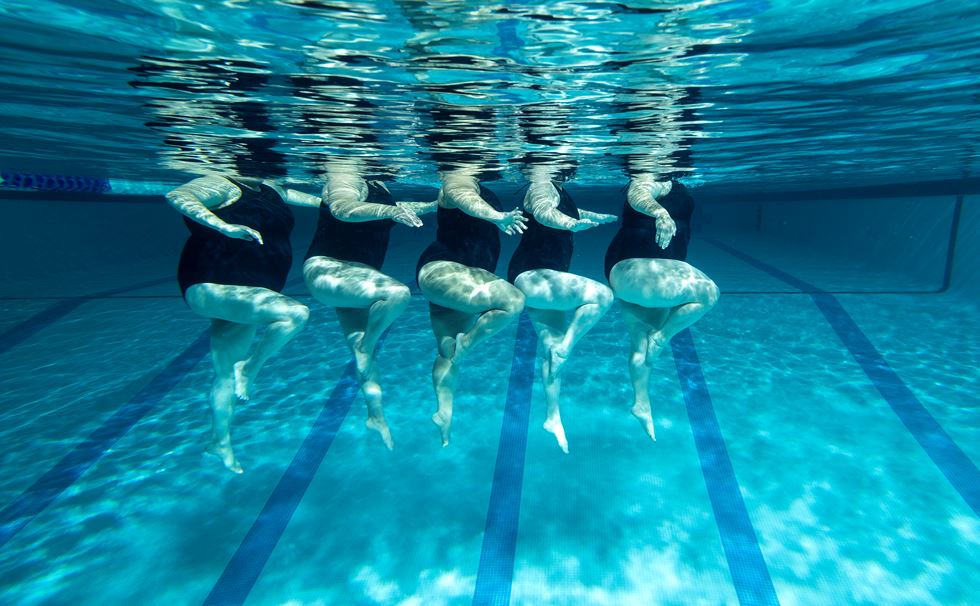

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes