Wembley isn't just a stadium — it was a vision and a pioneering adventure in the history of architecture

The 1924 Wembley Empire Exhibition was conceived on a vast scale, with a bewildering variety of displays that united such themes as Canadian butter, Tutankhamun and toffee tins. It also pioneered the architectural use of concrete, as Kathryn Ferry explains.

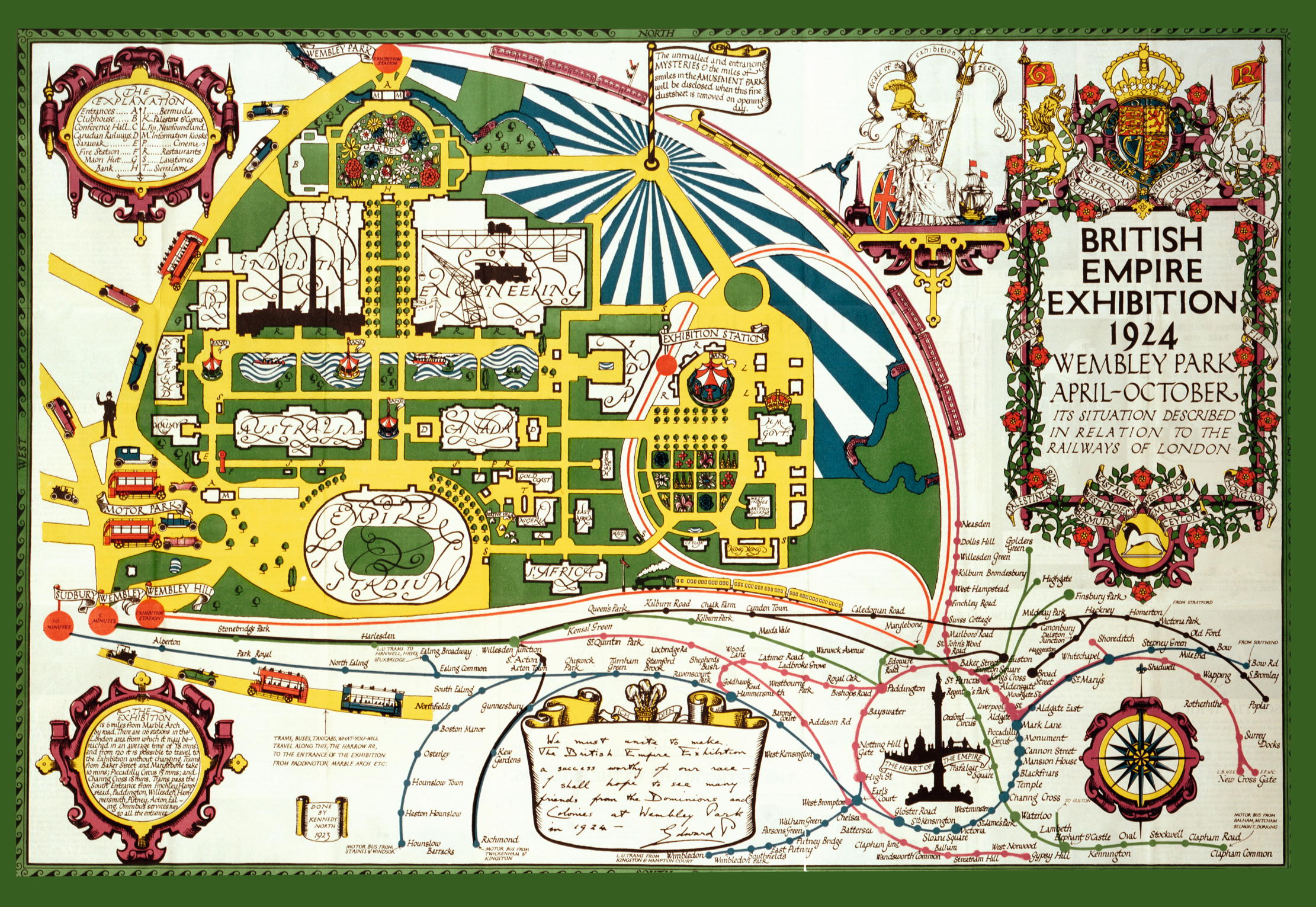

In summer 1924, a new pastime gripped the nation. People from all over Britain and the world travelled to the outskirts of London to go ‘Wembling’. It was something of an endurance event, because the 216-acre site built at Wembley was intended to offer a complete tour of the Empire at the largest international exhibition ever planned. No one could hope to see it all in a day, perhaps not even in a week.

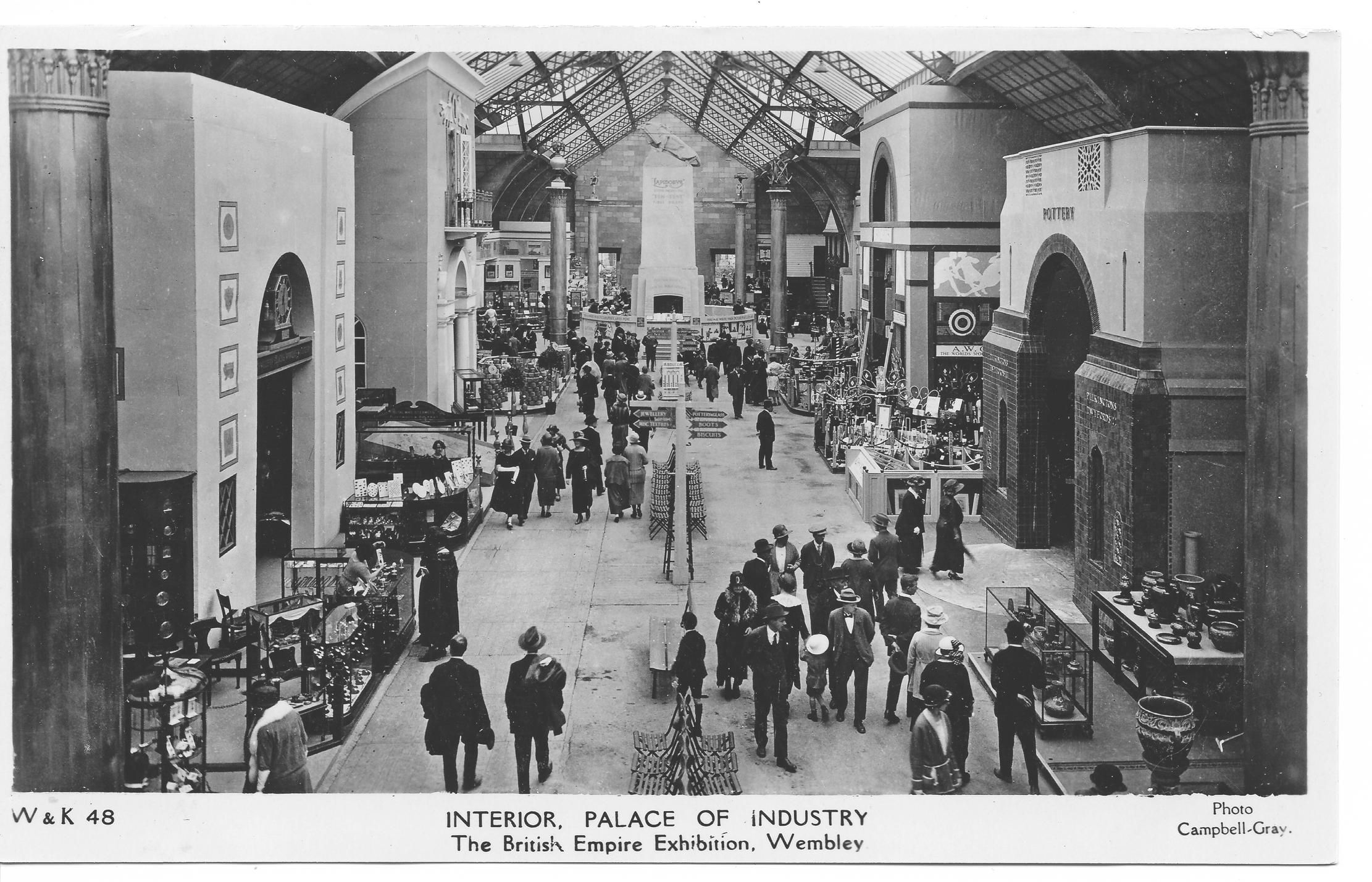

Seventy-eight governments took part; there were 1,000 exhibitors in the Palace of Engineering and 800 more in the Palace of Industry. Highlights included a sculpture of the Prince of Wales made of Canadian butter, a subterranean reconstruction of the recently uncovered tomb of Tutankhamun, a working coal mine, an Indian pavilion based on the Taj Mahal, the opportunity to ride an electric car around the site and the exquisite Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens (‘Life in miniature’, March 13). Commentators hailed it as the British Empire in microcosm, with its quirkiness generally perceived as a strength, evidence of the cultural breadth united under the British flag. For writer G. K. Chesterton, the most attractive aspect of the Wembley Exhibition was its ‘quality of patchwork… the juxtaposition of disjointed and diverse civilisations and arts and architecture’.

Historians have paid it scant attention. Writing for the Architectural Review in May 1924, Harry Barnes observed that the British Empire Exhibition has ‘a difficult name, even the Prime Minister feels it’. Held six years after the First World War, the same interval as would later occur between the Second World War and the Festival of Britain, the exhibition was intended to celebrate collaboration and friendship, but belief in the notion of Empire was already waning. For Barnes, it brought ‘elusive memories of nursery rhymes at which I clutch only to find them gone’. Diminishing support for Empire meant that, despite its scale, the Wembley event was quickly forgotten.

This fitted the changing politics of the 20th century, but obscured the innovation of what can be considered the world’s first concrete city. Country Life was not alone in noticing a remarkable thing about Wembley: ‘He who disparages at a distance on sight becomes an ardent admirer. The architecture alone will be a revelation to most people; astonishing feats, never dreamt of before, have been achieved with concrete and steel frames.’

The exhibition layout and main buildings were the work of John W. Simpson (1858–1933), Maxwell Ayrton (1874–1960) and Owen Williams (1890–1969). Simpson, a former president of the Royal Institute of British Architects known for his internationalist outlook, had co-designed the Palace of Fine Arts for the 1901 Glasgow International Exhibition (now the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum) and was a specialist in school buildings, notably Roedean in East Sussex. At Wembley, he was senior partner, but contemporary reports, confirmed by Simpson’s obituarist, suggest that the energy and invention came from the pairing of Simpson’s younger colleague Ayrton with consulting engineer Williams. Harry Barnes described theirs as a ‘marriage of true minds… they have shown the possibility of collaboration and co-operation between architect and engineer, each enhancing the work of the other’. Together, they revelled in the chance to exploit new materials with extraordinary results.

Unusually, the main exhibition structures were designed to be permanent. The most loved and enduring was Wembley Stadium (Fig 5), which first hosted the football cup final beneath its domed towers in 1923. Concrete construction answered the requirement for longevity, but it had other benefits in the aftermath of war, too. Both bricks and bricklayers were in short supply. Quick to make and cheap, concrete did not require a traditional labour force. When he cut the first sod at Wembley Park in January 1922, the Duke of York voiced his hope that the exhibition building programme would provide much-needed work for unemployed veterans.

The appointment of Williams was crucial. He was among a very small group versed in the early development of reinforced concrete, having worked for the Indented Bar and Concrete Co and then the Trussed Concrete Steel Co, following graduation from London University in 1911. During the First World War, he gained expertise in aeronautical engineering before designing concrete ships for the Admiralty. Through the 1920s and 1930s, he would go on to design major Modernist buildings, including the Dorchester Hotel in London, Boots factory buildings in Nottingham and the Pioneer Health Centre in Peckham, south London. He brought all his varied talents to Wembley and was recognised for his expertise with a knighthood at the age of 34. Additional experience of working with concrete came via the contractors Sir Robert McAlpine and Company.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Ayrton and Williams designed their buildings to showcase concrete in its raw state. Reactions were mixed; Prof Charles Reilly found the ‘mud colour’ of the naked material ‘infinitely depressing’. Prof Patrick Abercrombie called it ‘frank and grim’, but also acknowledged its originality as the ‘extreme opposite to the florid plaster treatment of outrageous Moorishness’ so frequently adopted at exhibitions. For ordinary visitors, the scale of the endeavour (Fig 3) was perhaps as impressive as the greyness, as colourful gardens and kiosks helped moderate the effect.

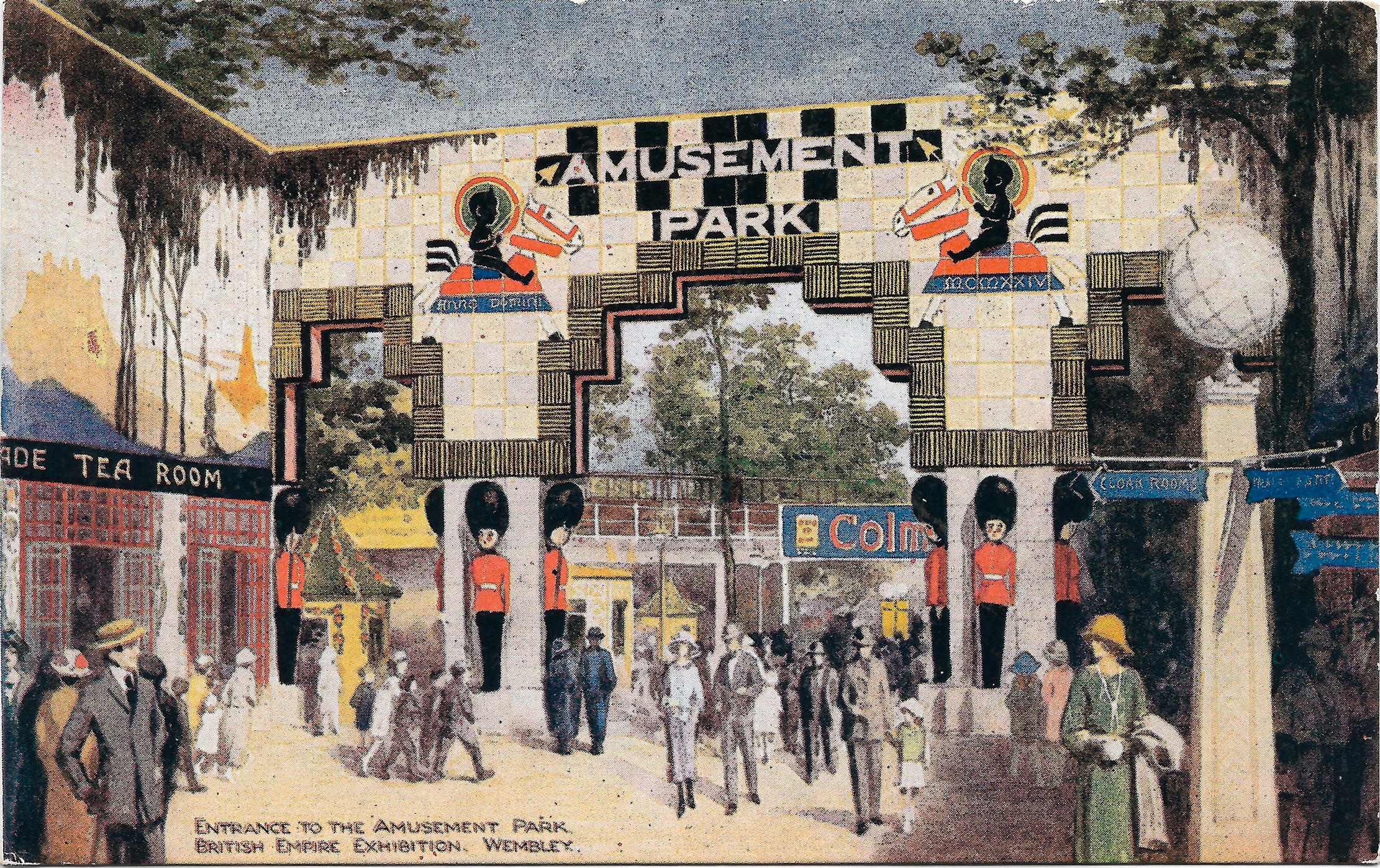

Entering from the north, people were funnelled by the curved arms of a concrete colonnade towards the central avenue, flanked on either side by vast palaces dedicated to British industry and engineering. Below them, the pavilions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and India looked onto an artificial lake spanned by the parabolic arches of concrete bridges. Sitting at the apex of the plan was the 100,000-capacity Empire Stadium. In the north-east corner, an amusement park (Fig 2) took up almost 50 acres. Between it and the stadium, smaller pavilions introduced the public to baldly stereotyped architectural styles from around the Empire, using more concrete. At the centre of this area was the British Government Pavilion.

Although it was criticised for being stuck out on a limb, the pavilion itself was widely acknowledged as the site’s highest architectural achievement. In his posthumously published book Interwar, architectural historian Gavin Stamp called it ‘a severe temple, as much Egyptian as Greek, stretched horizontally’. The symbol of Wembley was a lion and six of these guarded the entrance, a lofty portico given added dignity by the gilded grills set between its square piers. The British Government Pavilion took only eight months to build, its walls cast in situ using timber formwork. To avoid ugliness and mask any irregular finish between one day’s concreting and the next, deep horizontal lines or rustications were created across the façade. Vertical fluting provided extra texture. By using such techniques, the exhibition structures managed to combine a simplified yet monumental classicism with innovative construction methods. The Illustrated London News declared that: ‘If the style is to have a name it must be Georgian, for it is essentially the product of our own day.’

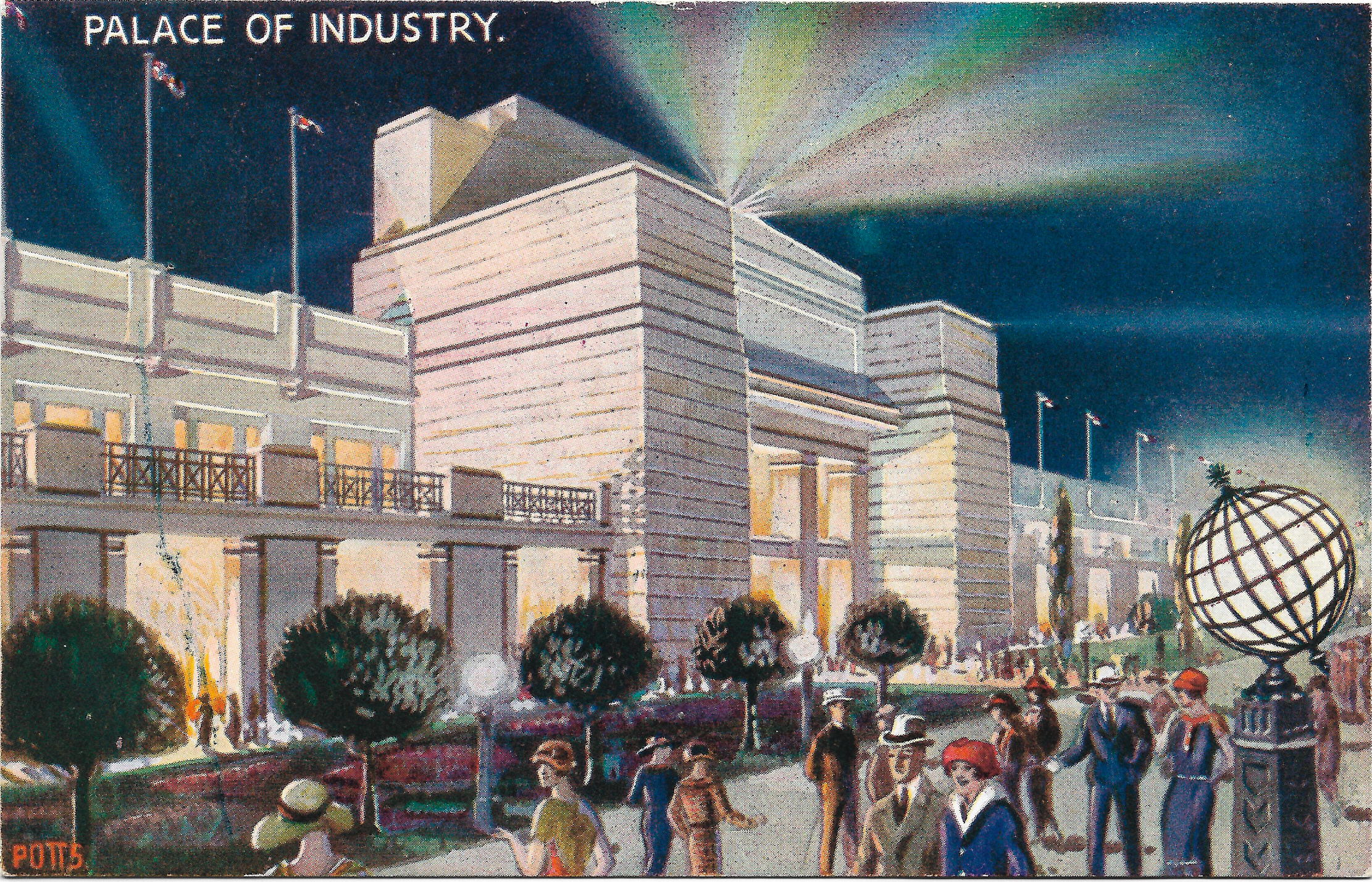

A sense of progress was also evident inside the Palace of Industry (Fig 4) under the guiding hand of Sir Lawrence Weaver, director of UK exhibits and former Architectural Editor of Country Life. He not only persuaded exhibitors to move away from the layout of internal streets, a legacy of the 1851 Great Exhibition, he also won acceptance for the idea that displays should be designed by trained architects. This approach delivered a new artistic unity, with each product section having its own hall accessed through a decorative portico (Fig 6). The commissions won by Sir Clough Williams-Ellis, who began work on his Welsh coastal village at Portmeirion a year later, exemplify the range of clients. He brought an elegant simplicity to the porticos of both chemical manufacturers Brunner Mond and Carson’s chocolate-makers, also designing the Ulster Pavilion and the Concrete Utilities Bureau in the exhibition grounds. Edward Maufe was responsible for the jewellery section, food section and Moorcroft Pottery entrance. Elsewhere in the pottery area, Oliver Hill designed arched porticos for Pilkington’s, Wedgwood and Royal Doulton. E. Vincent Harris created a stately classic portal for the Cement Marketing Co that bore inscriptions in the manner of a triumphal arch. Meanwhile, Percy Morley Horder provided Cauldon Pottery with a colonial-style entrance and devised a baronial castle front for the exhibition of Scottish whisky.

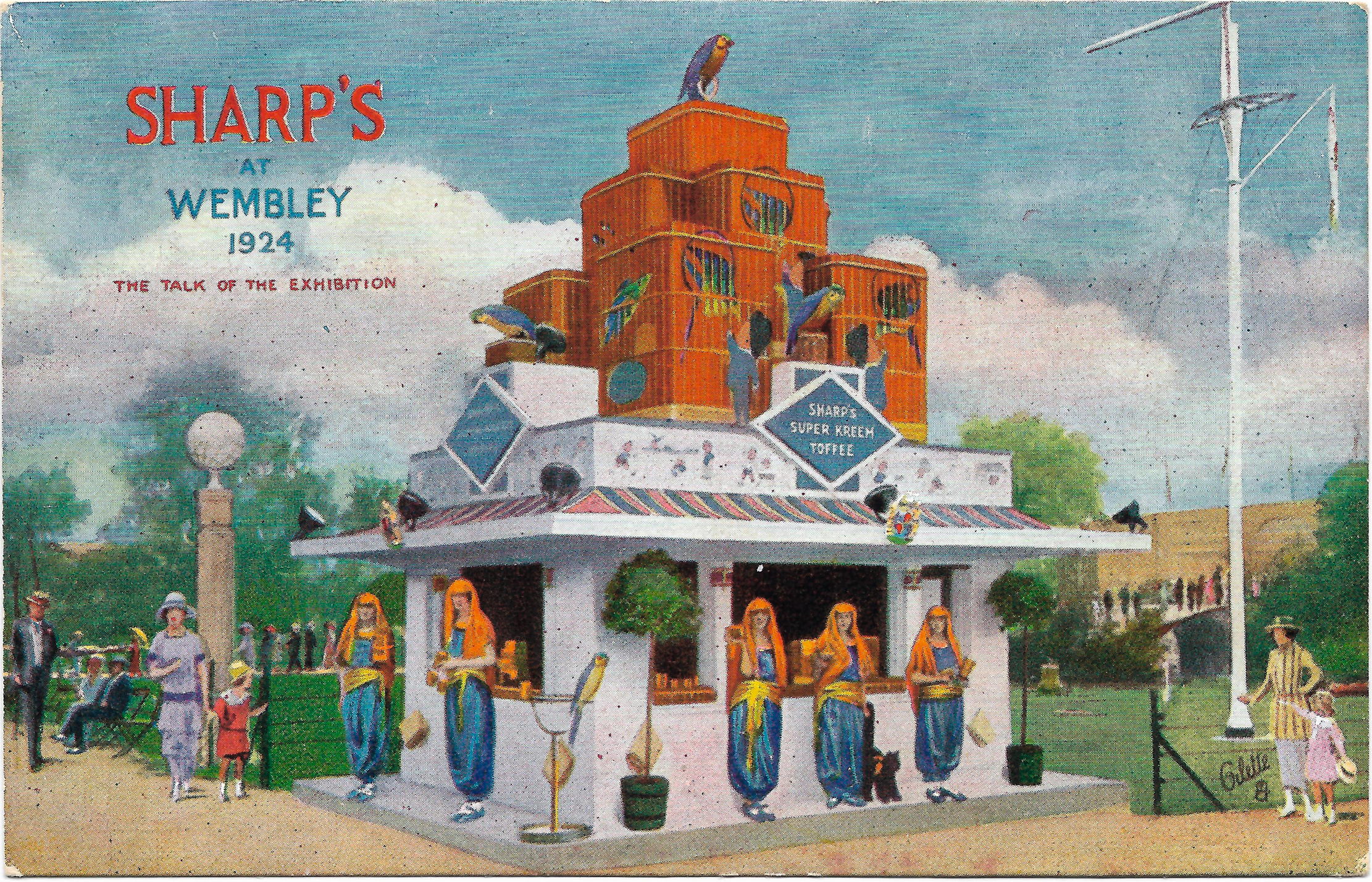

In the Palace of Engineering, then the largest concrete structure in the world, Lutyens’s pavilion for Teesside steelmakers Dorman Long and Co stood out, its big black scagliola columns paired with a red ceiling. Sir Edwin Cooper also produced a fine large Doric portico for the Port of London display. It was Joseph Emberton, however, who seemed to shine as the most successful and prolific author of small structures around the site. The official guidebook called him a ‘young architect with ideas of his own’, proclaiming the novelty of his advertising kiosks that turned poster art into three dimensions. Taking well-established brand identities, he built Sharps’s toffee kiosk out of toffee tins (Fig 1) and topped the domed Oxo pavilion with an Oxo cube. Weaver praised Emberton’s front for the Nobel Industries Hall as the best thing in the Palace of Industry because ‘he has been content simply to emphasise the big lines he found’. Less than a decade later, Emberton would be one of only two architects to represent England in America at the 1932 International Exhibition of Modern Architecture in New York with his Royal Corinthian Yacht Club at Burnham-on-Crouch, Essex.

In the framing of post-First World War tastes, there was one other significant location. Alongside paintings and sculpture, the Palace of Arts featured an extremely popular suite of six period rooms. The choice of timescale was itself indicative, starting with a praiseworthy panelled apartment of about 1750 before slipping into the Regency and then ‘a painfully faithful rendering’ of the mid-Victorian parlour. This, in turn, gave way to what organisers deemed the sounder influence of William Morris and William De Morgan of about 1888 before visitors were presented with two rooms from 1924.

The designs for a dining room and hall by Lord Gerald Wellesley and Trenwith Wells and a bedroom by W. J. Palmer-Jones were chosen in a competition organised by Country Life. The panel of judges, including Lutyens, Weaver and Morley Horder, expressed disappointment at the continuing reuse of historic styles among entries that were required to show ‘something which is markedly of our own time’. In the light of what was to come in Paris, where the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Art launched Art Deco upon the world, these Wembley schemes look distinctly tame.

Eighteen million visitors went to Wembley between April and November 1924 and the exhibition opened again to recoup costs in 1925. Its greatest legacy was the Stadium, although Grade II listing could not save that from total reconstruction in 2003–07.

By the mid 1970s, concrete had become too commonplace for there to be much interest in its early manifestations. A local campaign fought hard, but failed to save the British Government Pavilion and the Palace of Engineering, which were repeatedly turned down for statutory protection. A century on, the Imperial vision promoted by the Wembley exhibition seems hopelessly outdated. That should not detract, however, from its architectural interest as a pioneering adventure into the potential of concrete as a building material.

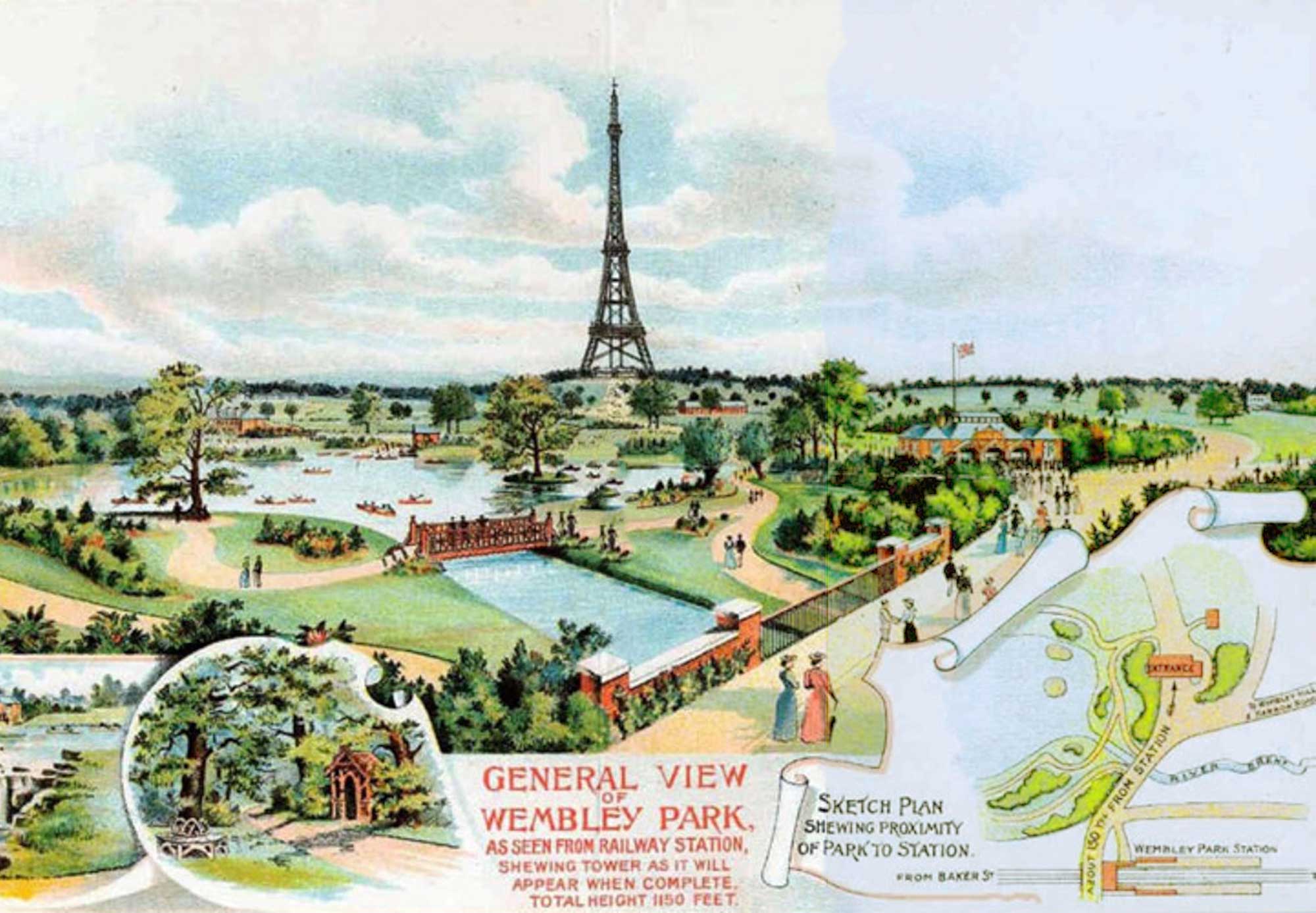

How London nearly had its own Eiffel Tower

England and France competed fiercely for bragging rights in the 19th and early 20th centuries — but no version of France's

The Flying Scotsman: How the first 100mph locomotive became the most famous train in the world

The first train to officially hit 100mph may not even have been the first, and didn't hold the rail speed

Sir Edwin Lutyens: Britain's greatest architect?

This year is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Edwin Lutyens, one of Britain’s most celebrated architects. John Goodall