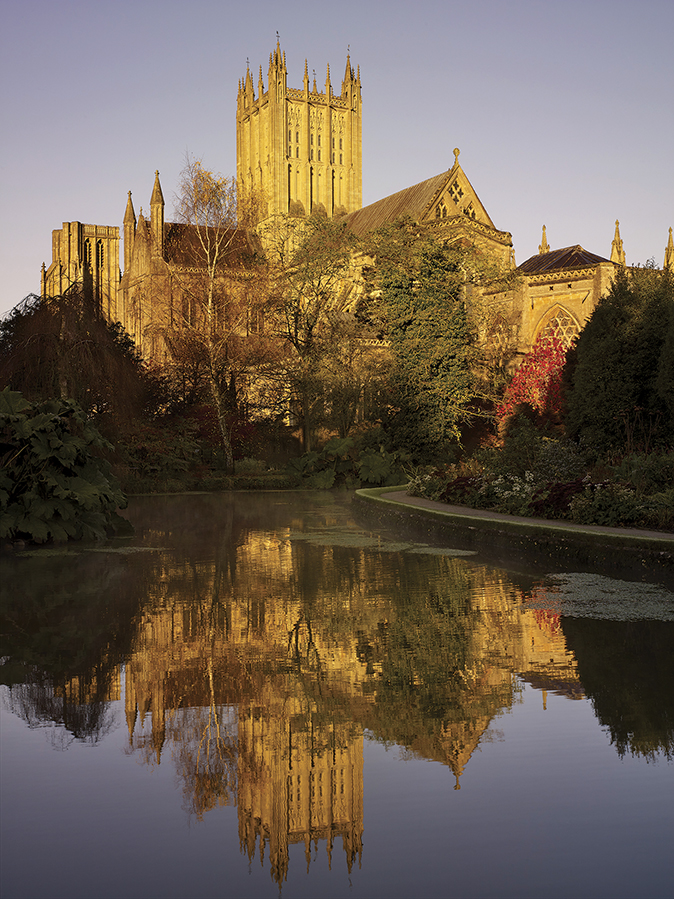

Wells Cathedral, Somerset: A symphony of architecture

In the first of two articles, John Goodall describes the architectural development of Wells and the struggle of its late-medieval clergy to win the church its now-familiar status as a cathedral.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Wells takes its name from the natural springs that rise up from the ground in the shadow of the cathedral. From them, indeed, the entire history of the site flows. For it was to the springs that the first settlers were presumably attracted in the Roman period and, then, after a long period as a focus for religious ritual, a mausoleum was constructed beside them for an important burial between the 5th and 7th centuries.

Nothing is known about the individual in question, but he or she was laid to rest in a square mausoleum and Christian burials were later made around it. By the 8th century, this area had assumed sufficient importance for the mausoleum to be demolished and enlarged as a chapel, possibly with the remains of the original incumbent enshrined as a relic. At the same time, a powerful family – again un-named – began to use the new chapel as a burial place.

It is likely that the construction of the chapel coincided with the erection of a major new church just to the west, across what is now the site of the cathedral cloister. With regard to this project, at last, we have names and dates. Medieval accounts attribute King Ine of Wessex both with the erection of a new church at Wells and the foundation of other neighbouring religious institutions, including the abbeys of Muchelney and Glastonbury. In 766, Ine’s church was complete and is referred to as ‘the Minster near the Great Spring at Wells’, dedicated to St Andrew.

Little is securely known about Ine’s church, but, in 909, it became the cathedral of the bishopric of Somerset following the sub-division of the diocese of Sherbourne. It served this purpose for more than 150 years and must have been adapted over this time. The last Saxon Bishop of Wells, appointed by Edward the Confessor in 1061 – a churchman from Lorraine named Giso – probably linked the free-standing chapel, by now a Lady Chapel, with the church.

Together, they formed a building about 300ft long, comparable to such major English churches as St Augustine’s Canterbury (330ft) and Winchester and Glastonbury (about 260ft). It lay at one end of the main market square of the town, approached directly up what is now the High Street.

Bishop Giso died in 1088 and, two years later, following a grant from William II, his successor transferred his cathedral to the Benedictine Abbey of St Peter’s, Bath. The departure of the bishop had two important consequences. Across the kingdom, the new Norman masters of England were reforming ecclesiastical institutions and constructing new churches on a vast scale in a monumental style termed the Romanesque. The demoted Wells, however, governed since the time of Bishop Giso by the rule of St Chrodegang, escaped both processes until the 12th century.

When institutional reform came in the 1130s, the Anglo-Saxon community was reconstituted after the example of Old Sarum – later Salisbury – as a regular college of priests under the control of a Dean (rather than as a monastery served by monks). It was a constitution it would preserve, with adapt-ation, for the remainder of the Middle Ages.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

At the same time, there is archaeological evidence that Wells was provided with a cloister and also, perhaps, a chapter house for collective gatherings. It was to be another 40 years, however, before the church itself was replaced.

This task was undertaken by Reginald de Bohun, who was consecrated Bishop of Bath in 1174. By 1180, Bishop Reginald had initiated the complete reorganisation of Wells. A new Gothic church, coherently planned on a cross-shaped plan, was begun across the site of the Romanesque cloister. Its intended west front overlooked an undeveloped site to the north of the marketplace, creating the magnificent expanse familiar today as the cathedral green. While construction got under way, the Saxon church, lying beside its successor, but on a slightly different alignment, continued in use.

The most obvious explanation for Bishop Reginald’s vastly ambitious architectural initiative – nothing less than a new great church in a Gothic idiom, one of the first in the kingdom – was that he aspired to re-establish Wells as his cathedral. If that is so, however, his vision was not straight-forwardly or immediately fulfilled.

Work to the new building progressed from east to west and was undertaken in clearly defined stages. The eastern arm, enclosing the high altar, was probably completed by 1184, followed by the transepts and then the eastern section of the nave by 1210. At each stage, the church had a different point of entrance, culminating with the great north porch of the nave completed in 1207.

In many technical details, the design of Bishop Reginald’s anonymously designed church is informed by local Romanesque precedent. Bundles of three shafts, a distinctive West Country motif from the 12th century, for example, are used to support the vault and ornament each face and angle of the nave arcade piers. The linear aesthetic they create, however, may reflect a Gothic sensibility pioneered in lost Cistercian buildings of the region.

When sufficient of Reginald’s church had been completed, the canons moved into their new choir beneath the crossing, then the old church was demolished to create space for a new cloister (rebuilt in its present form from about 1460) and at least one of its fittings, the font, was moved into its successor.

Evidence for the demolition of the old church is provided by a decision in 1196 to preserve and restore one element of it: the Lady Chapel beside the springs. This lay immediately to the east of the new cloister, to which it was now connected. The chapel became a monument to the deeper history of the site, preserving its ancient alignment, and was much adapted in the 13th century. It was then extravagantly rebuilt on a cruciform plan (and on true axis with the church) from 1477 to 1486, but fell victim to the Reformation and was demolished after 1552.

The decision to preserve the ancient Lady Chapel may have been bound up with a crisis in the affairs of the see of Bath that entirely distracted the attention of Bishop Reginald’s successor, Savaric, from the redevelopment of Wells. Consecrated in 1192, he was involved in negotiations to release Richard I following his capture on return from crusade. He persuaded the Emperor – and the Pope endorsed the idea in 1196 – to make it a condition of the King’s release that he should assume Glastonbury Abbey as his cathedral.

The monks of this ancient and vastly wealthy Benedictine monastery (where the bones of none other than King Arthur had recently been discovered) were outraged and fought off this predatory assault. To enhance its own claims to be a cathedral, in about 1200, Wells compiled a new history called the Historiola, incorporating biographies of its Anglo-Saxon bishops. At the same time, eight effigies of these men were installed around the choir.

In 1219, after a period of interdict and civil war, Bishop Saveric’s successor from 1206, Jocelin, formally renounced his claim on Glastonbury. He then successfully petitioned the Pope to make him the bishop of the joint see of Bath and Wells. His interest in Wells may partly be explained by the fact that he was locally born, at Launcherley, and was a canon of Wells.

Bishop Jocelin reformed Wells as an institution as well as driving forward its architectural development, setting out the Bishop’s Palace that stands beside the cathedral. In about 1220, he also began the completion of the nave. Work to this was, at first, directed by the master mason Adam Lock and then, from 1229, by Thomas Norreys.

It is to Lock that the design of the astonishing west front can probably be attributed: a huge and coherently planned screen of sculpture (although its unusual breadth, created by adding towers to the sides of the aisles rather than above them, was inherited from the 1180s plan). Famously, it incorporates a gallery for singers so that the company of heaven carved across it could be given voice for such occasions as the Palm Sunday procession.

Entrance is through relatively tiny doors, possibly an architectural reference to the difficulty of man’s passage to Heaven. Traces of colour show that parts of the façade and its sculpture were painted. The whole church had been substantially completed when the church was dedicated on October 23, 1239.

Following the death of Bishop Jocelin in 1242, the canons of Wells embarked on a ruinously expensive legal dispute with the monks of Bath over the right to elect his successor. Fighting the case, by 1245, the chapter accrued a massive debt of 1,775 marks in the Roman curia. The consequent shortage of money probably brought all building to an end, including the work of painting the west front and furnishing it with sculpture.

The dispute did, however, formalise the relationship between Bath and Wells: elect-ions would be held alternately at each place and the Bishop enthroned in both churches. In the light of this settlement, the chapter further expanded to 53 canons in 1264. With Lincoln, it now emerged as the largest of any non-monastic English cathedral.

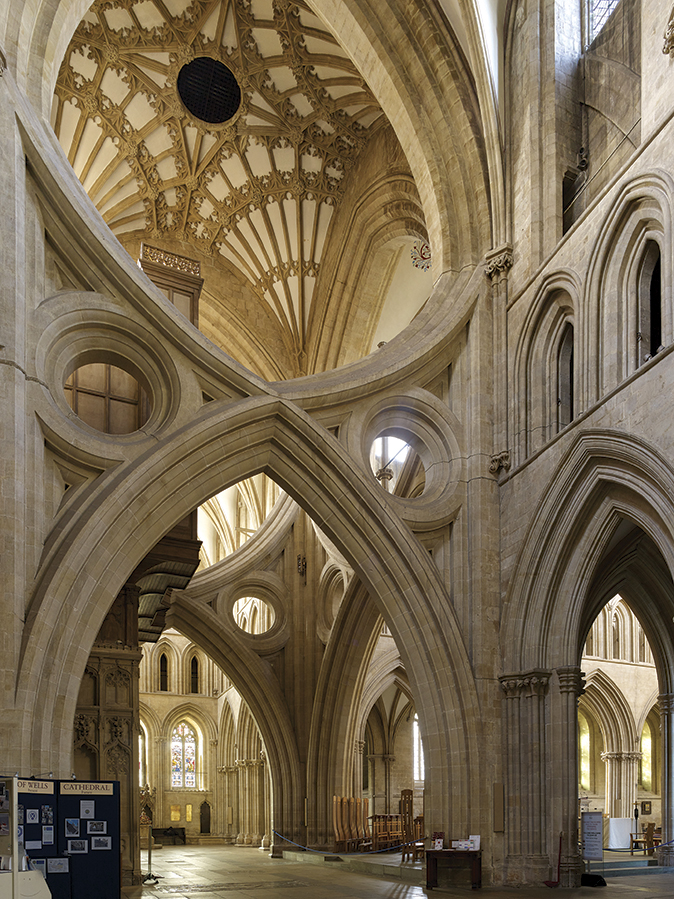

As its financial fortunes recovered, the chapter began an appropriately magnificent chamber for its formal gatherings. The octagonal chapter house, completed by 1307, will be described next week. In 1315, a fine was levied on the chapter to pay for another prestige project: a central tower over the church. This structure worsened existing structural difficulties with the crossing and, in the 1330s, demanded the installation of a huge scissor arch. It is attractive to imagine that the form of the arch was consciously inspired by the cross of St Andrew, the dedicatee of the church. What is clear, however, is that the Dean and chapter wanted a more immediate patron and relic than an Apostle.

In June 1324, they petitioned the Pope to canonise a former bishop of the see, William de Marchia (d.1302). At the same time, doubtless to create an appropriately magnificent setting for his intended shrine behind the high altar, they initiated the extension and reconstruction of the eastern arm of the cathedral. This hugely important project was directed consecutively by the master masons Thomas of Witney (probably) and William Joy, who particularly drew ideas for the design from the great royal chapel of St Stephen at Westminster (Country Life, April 1, 2015) and St Augustine’s Abbey, Bristol (now the cathedral).

Work began with a new Lady Chapel on an octagonal plan with an extra-ordinary dome-like vault. It was linked to the main volume of the choir by a cross-aisle or ambulatory. Finally, in the 1330s, the eastern arm was lengthened and remodelled and the canons’s choir transferred into it from its original position beneath the crossing.

The vaults of the new eastern arm create sophisticated inter-relationships of space between the different elements of the building as well as between its structural units or bays. As an added sophistication, they incorporate decorative patterns derived from window tracery. Incredibly, the influence of the architectural ideas developed here can later be detected not only in England, but across Europe.

Another important element of the building’s aesthetic is the way in which materials combine to symphonic visual effect. The walls and windows of the choir, for example, dissolved into tiers of niches filled with figures of saints in stone (now lost, along with the high-altar reredos of tiered niches) and glass (which survives).

In perfect living mirror of this artistic evoc- ation of the company of Heaven in the architecture, the canons gathered for Divine Service in canopied stalls in the choir beneath.

In the event, Bishop Marchia was never canonised, yet the project to dignify his body created one of the most opulent and inventive buildings of the Middle Ages. From the late 14th century, the church continued to develop on a sumptuous scale, notably with the addition of chantries and tombs as well as three new towers: a pair consecutively built over the west front and a remodelled central tower following a fire in 1439.

At the Reformation in the 1540s, Wells preserved its claim to be a cathedral. The attendant religious changes, however, would transform the life of its community of clergy, which we will explore in next week’s description of the cathedral close.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.