Villa Capra, aka La Rotunda, and how a 16th century Italian inspired some of Britain's greatest country houses

The ideal form of the Villa Capra, ‘La Rotonda’, in Italy has fascinated British patrons and architects since the 18th century. William Aslet considers how they have experimented and developed its ideas.

The name of the Italian architect Andrea Palladio has today become disassociated from the historical context in which he lived and worked. To talk of ‘Palladianism’ is not to refer to the world of Italy’s Veneto in the 16th century, where the architect made his career; rather, for its admirers, it is to speak of mathematical harmony and proportion in architecture, as well as the ideal of a rational, aesthetic perfection tempered by the Roman past.

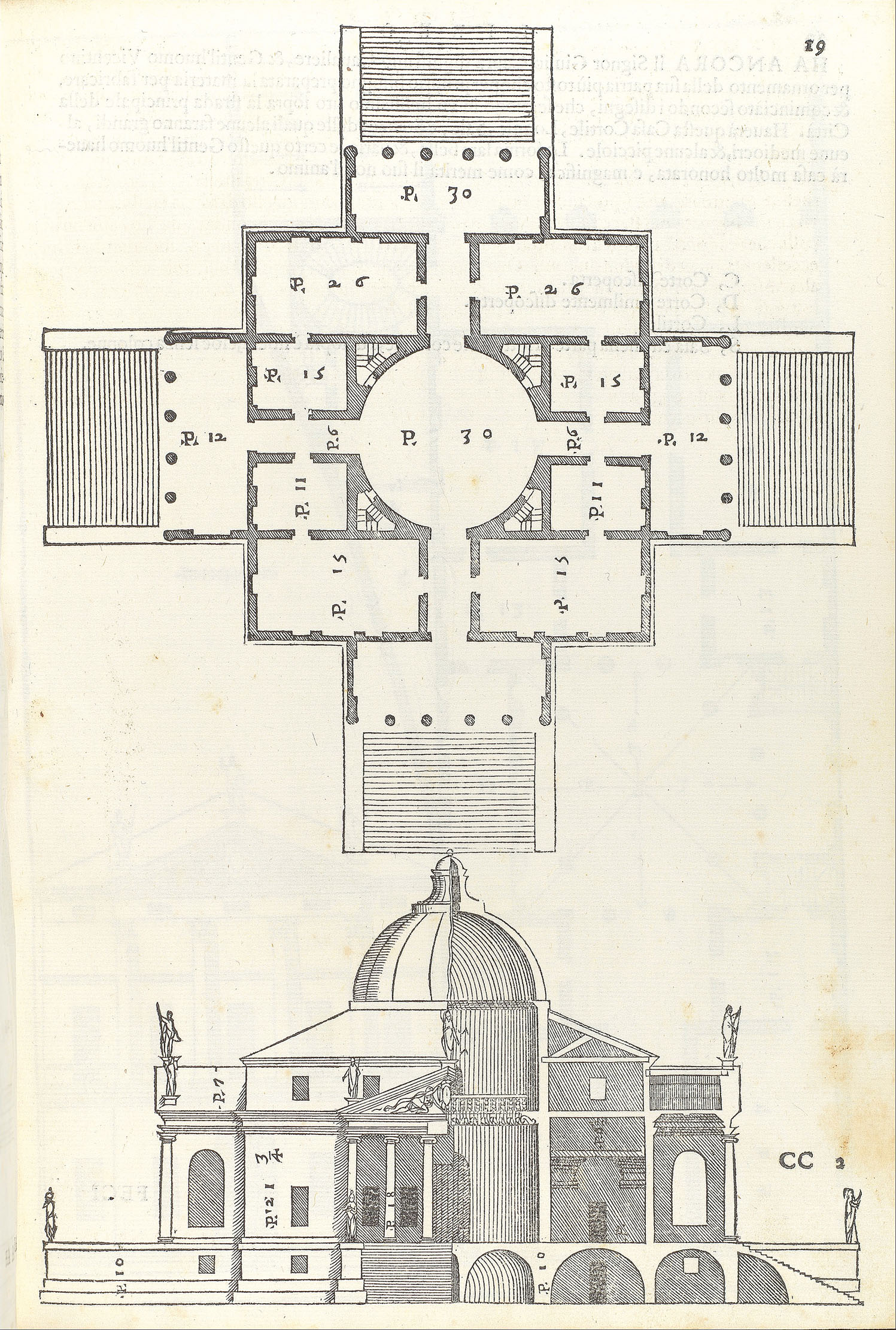

The building elevated above all others as an expression of these aspirations is Palladio’s Villa Capra, ‘La Rotonda’. Situated in the hills outside Vicenza, its plan is bold in its simplicity. It comprises two perfect figures, a circle nestled within a square, the former containing a domed hall and the latter the principal rooms, all of which are symmetrically arranged. In reflection of the perfect plan, each of the four façades is defined by a nearly identical portico of the Ionic order approached by a steep flight of steps.

Since its construction, the building has stood as a challenge to architects inspired by the Palladian ideal, one that has particularly engaged British architects working on their native soil. This is perhaps surprising, given the unsuitability of the Rotonda form to the British climate. In Italy, the porticos provide cooling breezes during the summer, whereas, in Britain, they are almost invariably the source of chilling draughts. Even in the 18th century, when the British mania for Palladio was at its peak, Alexander Pope ridiculed architects who were:

Proud to catch cold at a Venetian door Conscious they act a true Palladian part And, if they starve, they starve by rules of art.

It comes as no surprise, therefore, that the innovation of which Scottish architect Colin Campbell was most proud in his design for Mereworth Castle, Kent, finished in about 1723, was the manner in which he had succeeded in hiding 24 chimneys in the spaces between the roofs and domes.

Heating, however, was not the only difficulty posed by the Rotonda form. One of the most distinctive features of La Rotonda — its central dome — is also its most inhibiting, as it rises through the core of the house, forcing an architect to squeeze the rooms into the spaces around it. This was not as great a concern to Palladio as it was to Campbell.

Palladio’s villa was designed to be used as a summer residence for the scholarly churchman Paolo Almerico and so did not need to provide extensive space for accommodation. Campbell’s brief, by contrast, was to provide a house that his patron, John Fane, 7th Earl of Westmorland, could use to host his family and guests whenever he pleased. Clearly, for all the elegance of his design, the accommodation was insufficient, for, about 20 years after its completion, twin pavilions were built to provide more space.

Why, then, did architects such as Campbell choose to work with a form as unwieldy as La Rotonda? It was not due to a slavish devotion to Palladio alone, for when we look at examples closely we realise that none is a straight replica of his original.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Even Campbell’s Mereworth Castle, arguably the most concerted emulation of it, deviates from the prototype, with the symmetry of the plan disrupted by the inclusion of an English-style long gallery.

Some departures were more fundamental still. Nuthall Temple, Nottinghamshire (which was built in about 1750 and demolished in 1929), for example, was built not on a square, but on an oblong plan, with one end bulging out to provide a bay window.

Taken together, the group would be better considered as a Diabelli-like set of variations on an original theme than as a series of copies. What unites them, however, is a fascination with the problems posed by the perfect form and its realisation in a domestic context. Each tried to solve Palladio’s problem, but in its own way.

The most successful attempts at this were those that had the fewest constraints. Indeed, the Temple of the Four Winds at Castle Howard in North Yorkshire, by Sir John Vanbrugh, could be considered a more succinct expression of Palladio’s idea than even he had managed. Because the temple, which was built in 1724–26 for Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle, was intended to contain only one room, Vanbrugh had to wrestle with few functional considerations that would compromise the integrity of the plan.

The only occasional use for which it was intended meant that the four porticos — here tetrastyle, that is to say, with four columns, rather than La Rotonda’s six — did not cause him so much trouble as they did architects designing larger houses. Indeed, taking the porticos to represent the four winds would not have seemed so droll an idea to an architect such as Campbell.

With Vanbrugh’s example showing how well the Rotonda form lent itself to garden buildings, others followed his lead. In 1728, shortly after its completion, James Gibbs included designs of his own for Rotonda-style garden buildings in his influential publication A Book of Architecture.

Vanbrugh knew Palladio through the Italian architect’s I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, first published in 1570, of which Vanbrugh owned Fréart’s 1650 translation into French. He consulted it closely when working on the house and there is a copy in the library said to be annotated in his hand. But Vanbrugh is not the British architect most frequently associated with Palladio. That honour belongs to Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, whose Chiswick villa went up in about 1729, almost at the same time as the Temple of the Four Winds. Burlington’s villa is often regarded as the definitive Palladian statement in Britain.

Yet there is much about Chiswick House that differs from its supposed source. In fact, Vanbrugh’s example comes a lot closer to it. This is not because Burlington could not have designed such a Palladian facsimile, had he wanted. Built next to an earlier house, which was later demolished, Burlington’s villa was essentially the largest of the Classical buildings with which he adorned his gardens, and so — like Vanbrugh in the gardens of Castle Howard — he was not bound by the need to provide extensive accommodation.

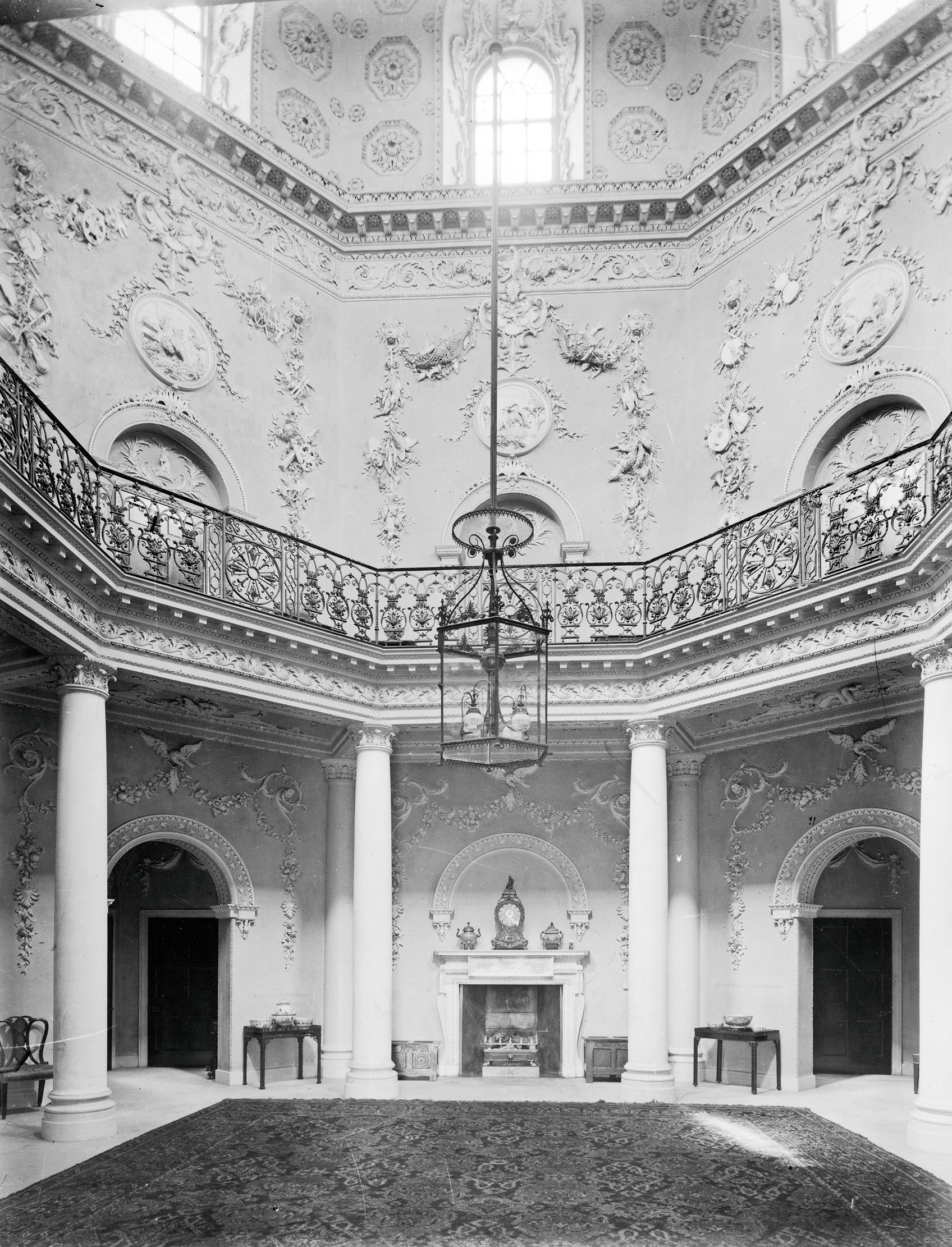

Burlington instead used his opportunity to experiment with the potential of the Rotonda form in different ways. His plan differs markedly from Palladio, even if the idea was his. The rooms, for instance, are not uniform, but of different sizes, and, most importantly of all, the dome is on an octagonal plan. Variety, then, as much as unity, is the watchword in Burlington’s design. Externally, he highlighted this by designing entrance stairs that force the visitor to enter the villa from the sides, inverting the head-on approach of the entrance steps to La Rotonda.

Some of these variances are due to Burlington’s study of the works of Palladio’s pupil Vincenzo Scamozzi. Yet to deconstruct the villa into a series of learned sources in this way would be to miss Burlington’s point, which was to show that he could create a design that was both new and inventive.

Original solutions have been found in the realm of garden buildings, but, as we have seen in the case of Mereworth, when dealing with a full-sized house the challenges multiply. These have, however, been met with notable success in the most recent example of the Rotonda-type in Britain, Henbury Hall, Cheshire, built in about 1985. The key? To wed insights gleaned from garden buildings with a more augmented scale.

From the start, Henbury benefited from an unconventional approach. It was born not of an architect’s plan, section and elevation, but from the imaginative fancy of a painter, Felix Kelly, who had persuaded his patron, the late Sebastian de Ferranti, of his idea for the house by painting an imagined view of it in oils, which looks as if it has been marooned from a capriccio by Rex Whistler. By initially conceiving the house in terms of scenography, Mr Kelly was not stifled by the problem of the plan. Indeed, his concern with painterly effect meant that the house, as he imagined it, looked not to the massy silhouette of Palladio’s Rotonda, but to the more slender and elegant profile of Vanbrugh’s Temple of the Four Winds.

Castle Howard had been much on Mr Kelly’s mind. He had recently been at work on the house, as Jeremy Musson outlines in his new book on Henbury, painting murals for rooms designed by young architect Julian Bicknell to replace those that had been burnt out in the fire of 1940. Mr Kelly’s commission was paid with funds raised by the 1981 television series of Brideshead Revisited, which had been filmed in the grounds of Castle Howard, and his painted view of Henbury is suffused with the Romantic, nostalgic atmosphere of the novel from which it was adapted.

To bring the painting into built reality needed the assistance of an architect. Quinlan Terry gave the first ideas, but it was Mr Bicknell, Mr Kelly’s collaborator at Castle Howard, who realised the project. Mr Bicknell’s ultimate guide to his approach was Mr Kelly’s painting. His focus on preserving the integrity of the design could be said to have generated his most original idea for the house, which was to open up the rooms at the front and rear, so that they make one interrupted space. The result is that, when moving through the house, the dome is a hidden surprise, appearing suddenly and dramatically. Its effect is thus preserved, although it does not dominate the plan as much as in the other examples we have considered.

What of the difficult porticos, of which there are a Palladian four? Mr Bicknell’s solution was to step the body of the house out slightly into each of them, so as to expand the size of the rooms behind them — something that had a precedent at Foots Cray, Kent (about 1754). In the summer, tea was frequently taken on the south portico; proof that to introduce such an Italianate feature is not entirely foolhardy in an English context. Proof, too, that the Rotonda remains a puzzle, the pieces of which architects will continue to delight in arranging and rearranging for many generations to come.

Marchmont: Scotland’s most ambitious Palladian house

An outstanding restoration project has transformed Marchmont. In the first of two articles, Roger White identifies the architect of this

A new future beckons for the magnificent, crumbling Palladian mansion that is 'the finest 18th-century house in Cumbria'

High Head Castle may currently only have two bedrooms and a small kitchen, but the opportunity to restore a property

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.