Upton House: A beautiful 1750 creation by Halfpenny, updated in a manner he'd have loved

Upton House, just outside Tetbury, is a beautiful Georgian house that has been brilliantly extended in a manner which is so sympathetic as to be scarcely noticeable. Jeremy Musson paid a visit, while Will Pryce took the photographs.

Upton House, not far from Tetbury in Gloucestershire, built in 1752, is a beguiling West Country example of the compact, Classical country house with a magnificent double-height hall.

Its story, however, does not simply rest in the Georgian era. In order to demonstrate the relevance of the Classical tradition he so admires, the present owner, Roger Seelig, commissioned a new double-height hall and wing that was completed in 2005 to replace modest service buildings mostly of the late 1930s on the north side of the house.

This new addition was designed by Craig Hamilton and is an original and witty response to the existing building, creating a generously scaled toplit room that transforms the circulation and feel of this much-admired Cotswolds villa.

The mid-Georgian Upton House was built for one Nathaniel Cripps, whose family had been minor landowners and magistrates in this area since the late 16th century. Not much is known about Nathaniel, but he left the house to his brother Samuel, described as ‘of Bristol’, who was then succeeded by his son, Thomas.

In A New History of Gloucestershire (1779), Samuel Rudder gives a long account of the medieval history of the manor and then says of the relatively new house only: ‘Thomas Cripps is the present principal inhabitant who has a good estate and an elegant new-built house in the hamlet where his family have resided for many generations and once enjoyed a larger estate than it does at present.’

Upton House might be seen as an attempt to assert an old family’s status in the county. The main show front to the south-east or, for simplicity, south – now the garden elevation, but originally the entrance – is a carefully modulated composition that echoes the details of certain designs published in James Gibbs’s Book of Architecture (1728), especially, perhaps, Plate 54.

Its ground floor is boldly rusticated, its windows incorporating a keystone and voussoir arrangement with an almost Vanbrughian quality. Above, the tall, first-floor windows have blind balustrades and are crowned by pediments supported on Ionic pilasters.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Over these is an attic storey with oval windows in the central three-bay projection of the façade. This centrepiece is crowned by a triangular pediment filled with a carved coat of arms.

Perhaps the most surprising feature of the house is that none of this rich ornamentation continues onto the side elevations; the side walls have huge expanses of rubble masonry and that to the west is even enlivened by inlaid patterns of stone.

It seems from 19th-century architectural surveys that the 1752 house retained part of an earlier 17th-century building as the domestic offices. Something of this is still just visible on the east side.

The identity of the original 18th-century architect of Upton House is still not known for certain. Marcus Binney’s confident attribution of the house on stylistic grounds to the Bristol-based architect William Halfpenny (which was made in Country Life on February 15, 1973) has, however, since been supported by others, including Nicholas Kingsley, author of the most important modern study of Gloucestershire’s country houses.

Halfpenny is most famous as a prolific producer of numerous pattern books, from the Art of Sound Building (1725) and A New and Compleat System of Architecture (1749) to Architecture Properly Ornamented (1752). Despite the resonance – even familiarity – of his name, as a result of his energetic publishing ventures aimed at the gentry and practical builder alike, there are surprisingly few works firmly documented to his hand.

In the 1730s, Halfpenny was active in Ireland and is said to have worked with Sir Edward Lovett Pearce and to have been his assistant on King House, Roscommon. He certainly designed a horse barracks at Hillsborough for the 1st Viscount Hillsborough in 1732 and Garrahunden House (later demolished) in Co Carlow in 1737 for Sir Richard Butler.

Halfpenny was clearly based in Bristol in the 1740s, as among his best documented work is the Coopers’ Hall in the city of 1741–43 (now the Bristol Old Vic), which shows some technical points of similarity with the slightly later Upton House.

He also completed the Redland Chapel there in 1742, possibly taking over an original design by the architect John Strahan. Halfpenny also designed a Chinese bridge at Croome Court in Worcestershire for the Earl of Coventry.

The magnificent double-height entrance hall of Upton, long used as a drawing room, is especially impressive. The walls are divided up by Giant Order fluted Corinthian pilasters, supporting a richly moulded entablature – a distinctive note are the half-pilasters, which meet in the corners of the rooms. The capitals of the pilasters are linked by floral swags in plasterwork of a fine quality.

The middle bay of each wall (above the doorcases and the chimneypiece) has an oil painting set into an ornate plasterwork frame, with a circular niche for a bust above. The plasterwork has been attributed to Joseph Thomas.

This room was originally flagged with stone and black marble and, although conceived as a grand entrance hall, it is likely this room was always to have been used for meals and receptions. This is not least because the other reception rooms of the original mid-18th-century house were relatively compact, with a single square room either side of the hall, now the sitting room and library.

The library has a chimneypiece framed by fluted Ionic pilasters, with a pedimented niche on either side (each fitted with bookcases).

Another virtuoso feature of the interior is the cantilevered oak staircase of a fine quality, with three turned balusters to each tread, rising the full height of the house, in an open well.

There was also a larger library on the north side, on a slightly raised level over the wine cellar and the kitchen and scullery were located in the older range on the north-west corner.

Upton House remained with the Cripps family until 1818. In 1866, the house was sold to Maj-Gen Sir Archibald Little. A new wing was added to the rear in 1870–71, designed by Gloucester architect F. S. Waller & Son, with French-style dormers, extending family and servant accommodation in the first and attic floor and a billiard room and smoking room on the ground floor. This must have replaced an older range, as the plan shown on the 1866 conveyance shows two wings around a courtyard to the north.

Waller & Son returned in 1892, shortly after the house was inherited by the general’s son, Maj Cosmo Little. A porch was also removed from the south front (shown in a photograph taken early in 1892) and the triangular pediment on curved brackets over the low main door presumably dates to these works (and is not shown on an earlier watercolour).

In conjunction with these changes, the present entrance on the west side of the building was created. It opens into a lobby that leads to the main stair. Some further works were carried out in 1939, for Mrs St Clair by Dowglass & Pyle of Cirencester, adding very utilitarian single-storey service rooms across the rear of the house and creating a garage in the former billiard room.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Upton House was let to the art historian Kenneth Clark (later Lord Clark), then Director of the National Gallery, to house his family and, during their residence, they entertained a number of artists here, including Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland.

The house was briefly filled with paintings of extraordinary quality, including Manets and Sienese primitives.

One visitor, Roger Hinks, observed: ‘The house itself is almost grotesquely filled full of pictures: positively encrusted, like the Casino Pio, as K remarked [referring to the Museo Pio Clementino in Rome]…

‘My bathroom contains a nude by Duncan Grant, a landscape by Tchelitchew, a Henry Moore and no fewer than three Graham Sutherlands.’

Other guests who came to Upton during the Clarks’ time included the composer William Walton and the music critic Edward Sackville-West. Later in the war, the house was requisitioned by the Land Army.

The St Clairs sold the house to Mr Seelig in 1983 and he has taken the greatest delight in the building, restoring the fabric, extending and planting the park and restoring the still-productive walled kitchen garden. He has also collected George II furniture and paintings appropriate to its date, including works by Romney, Joli and Panini.

He was also determined from the start to resolve the unattractive cluster of modest service buildings, some dating to the late 1930s, across the north of the house (the plans suggest that the older kitchen and scullery with low attic rooms over them that survived from the older house were demolished in 1939).

His vision was to add a bold piece of new Classical design – which would radically improve the circulation of the whole house and bring more light to this side of the interior – plus a new wing in place of the lost early wing.

He felt it was especially important that any new work honoured the appealing hybrid Classical tradition of the house and resisted initial official advice that a steel-and-glass addition would be a more appropriate approach.

He had been very impressed by a set of proposals for a new country house by Craig Hamilton and invited him to design the new additions to Upton House to his specific brief, which were warmly supported by architectural experts, including John Harris and David Watkin. These additions were completed in 2005 and awarded a Historic Houses Association commendation.

Mr Hamilton studied architecture at the University of Natal and moved to England in 1986. He set up in independent practice in 1991 and has since established an international reputation. Other recent works include the 2012 Bath House at Williamstrip, also in Gloucestershire – a 17th-century house remodelled by Sir John Soane, to which Mr Hamilton had also added a double-height rear hall similar in effect to that at Upton. His award-winning chapel at Culham Court in Oxfordshire was completed in 2016.

The new double-height hall and new wing at Upton House are an intelligent and witty response to the subtle Classicism of the existing house, which is both distinctive, but also carefully knitted in to the character and rhythm of the original.

The feel of the rear hall, with its fluted Ionic pilasters, and its toplit tunnel-vaulted ceiling, is of a later-18th-century neo-Classical designer, such as George Dance the Younger or John Soane. The detail is more spare, but with corner pilasters and circular niches for busts, echoing those of the original hall.

The new wing contains a new family kitchen and dining room and an additional bedroom, bathroom and dressing room on the first floor. It melds seamlessly with the new house.

First-floor Venetian windows give an Italianate flavour to both the new wing and the Victorian wing. These additions extend the accommodation of the house in a way that would have surely intrigued and impressed the inventive Mr Halfpenny.

They are also an important element in the way that Mr Seelig and Claire Ward Thomas have made Upton House work so well for hospitality and contemporary family life.

The Tudor mansion in Sussex where Lutyens and Jekyll pooled their talents

Legh Manor: The Tudor mansion in Sussex where Lutyens and Jekyll worked together

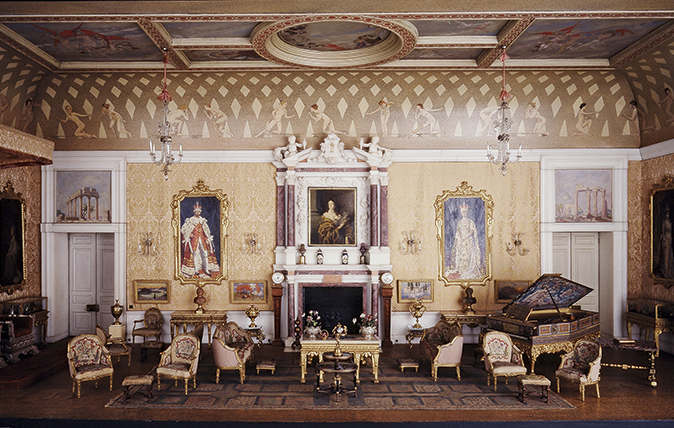

A doll's house fit for a queen: How Lutyens created a Lilliput for Queen Mary

A miniature palace designed by Lutyens and promoted by Country Life offers a fascinating perspective on the 1920s, as Gavin