Tudor house architecture: How England's great homes evolved in the 16th century

Country Life's architecture editor John Goodall looks at the architecture of the Tudor home.

In April 1521, Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, was urgently summoned from his seat at Thornbury, Gloucestershire, to appear before Henry VIII. The Duke could reasonably claim by birth to be the outstanding nobleman of his generation, boasting descent from Edward III and—arguably—possessed of a better claim to the throne than the Tudors.

He played the role of a great nobleman with proud perfection, both at home and in such public events as Henry VIII’s meeting with Francis I of France on the Field of Cloth of Gold, where he jousted and appeared in costume of fabulous expense. His birth and magnificence, however, also made him vulnerable to Court intrigue.

Receiving his summons, the Duke had a premonition that all was not well. According to Hall’s Chronicle, as he began the final leg of his journey on April 16, he had difficulty eating breakfast.

Having taken his barge — the transport of the wealthy between their riverside London houses — he called at the residence of Cardinal Wolsey. Landing at its river gate, the Duke was told that the Cardinal was sick. Nevertheless, he demanded some wine and was led to the cellar.

Despite the ‘reverence’ the Duke was shown, the lack of welcome was obvious. He ‘changed colour’ and continued on his way, only to be arrested on his barge by the Captain of the King’s Guard and marched to the Tower of London. A month later, he was condemned for treason and executed on Tower Hill.

As the world marvelled at the Duke’s fall, the royal administration set to work listing and seizing his possessions, including a carefully ordered muniment collection. Thanks to this, we have an exceptionally full picture of his property and lifestyle. As did all noblemen, he possessed an inherited portfolio of multiple residences. In this case, more than a dozen castles and manor houses spread across his vast estates, which extended from South Wales to Kent. These included buildings of every age stretching back to the 13th century. We often study buildings by period, but then, as now, in the living world architecture of every age co-exists.

In the dispassionate surveys of these buildings, the royal officers variously dismiss these residences as ‘old’ or admire them as ‘proper’, ‘uniform’ or ‘strong’. By these judgments, they reveal a clear preference for compact and regular architecture with big windows—in effect, architecture in the Perpendicular style first promulgated by the royal designers in the 14th century—and also for the prestigious and timeless aesthetic of the castle; the house that outwardly expresses the martial vocation of a nobleman (Fig 8).

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Many of these buildings served simply as administrative centres and were neglected or little used. Newport Castle, for example, had an exchequer chamber for receiving rents and a prison in repair, but its ‘proper lodgings’ were in decay. Others were fine residences, but neglected. These included Maxstoke Castle, Warwickshire, which the surveyor called ‘a right proper thing after the old building, standing within a fair and large moat full of fish, being builded four-square’ and entered via ‘a large base court’ of barns and stables.

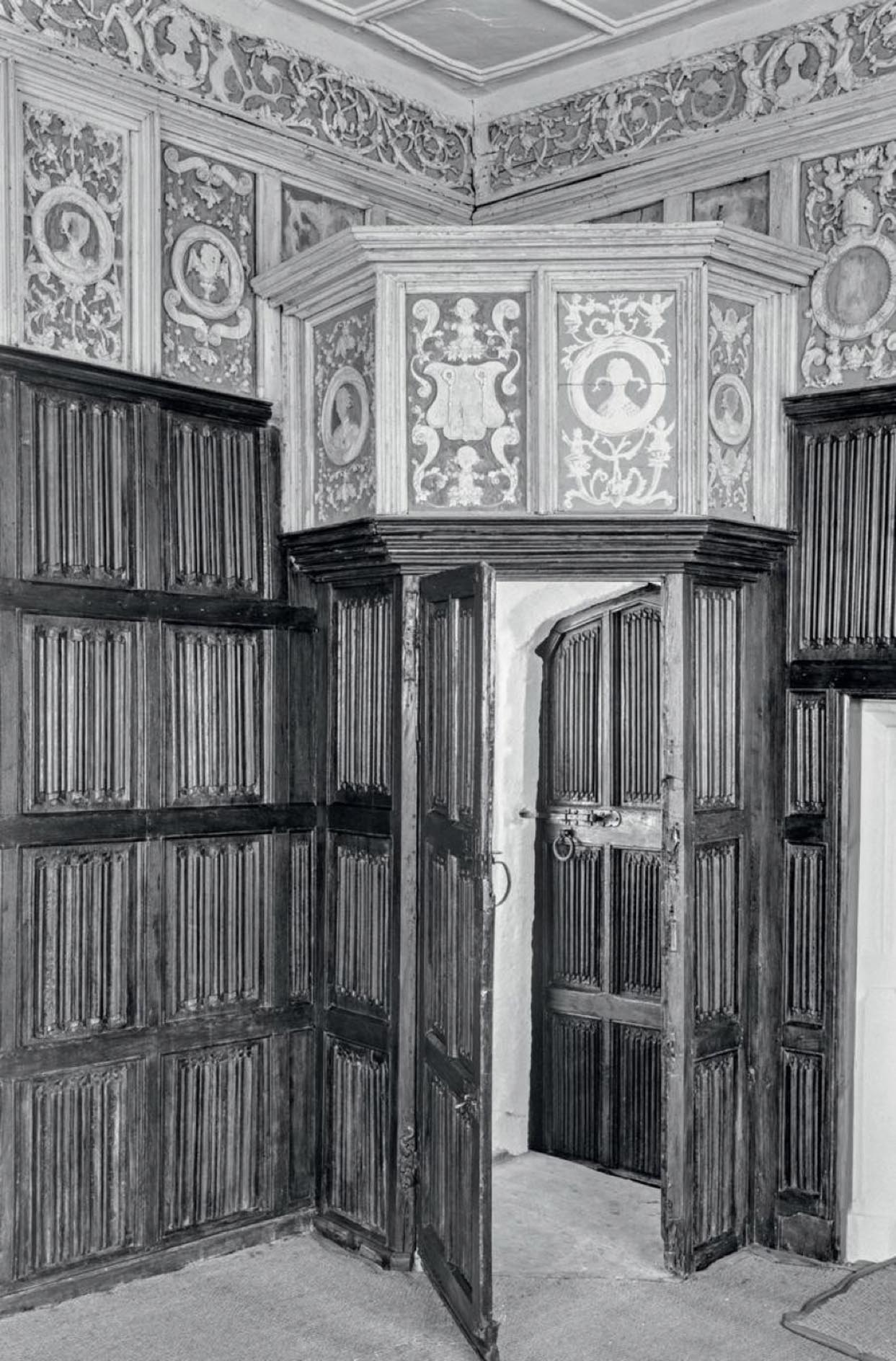

There were also a number of residences that were clearly used intensively by the Duke. Bletchingley in Surrey, for example, was described as ‘properly and newly builded’. Here, ‘the hall, chapel, chambers, parlours, closets and oratories be newly ceiled, with wainscot, roofs, floors and walls, to the intent they may be used at pleasure without hangings’. This final aside is very important. Hitherto, richly appointed interiors had always been hung with fabrics (of which tapestry was, from the 14th century, the most prized and expensive). Tapestry and fabrics remained common, but, from the early 16th century, it also became popular to furnish rooms with intricately carved wainscotting (Fig 1).

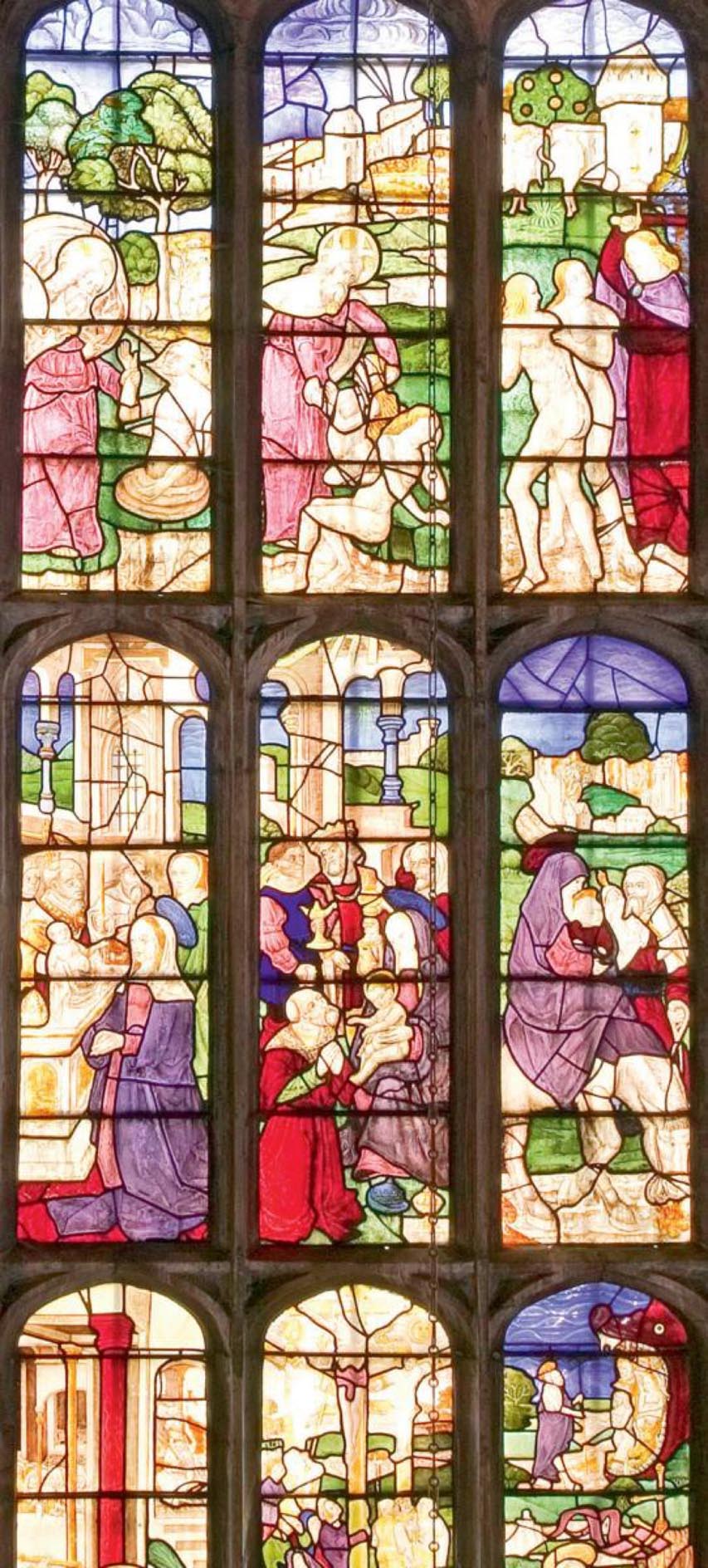

Like many of the most fashionable domestic furnishings in 16th-century England, such wainscotting was largely manufactured by Continental immigrants. The same group dominated stained-glass production (Fig 2) and other specialist crafts (Fig 6). Carving panels was a way of making them seem intensively worked, thus both expensive and ‘curious’. Hence the complexity of so-called ‘linenfold’ panelling, which gave the effect of symmetrically crumpled fabric in wood (Fig 3). These craftsmen brought a fashion for ‘grotesque’ or ‘antic’ work ornament, too, derived from classical paintings found amid ruins in Rome.

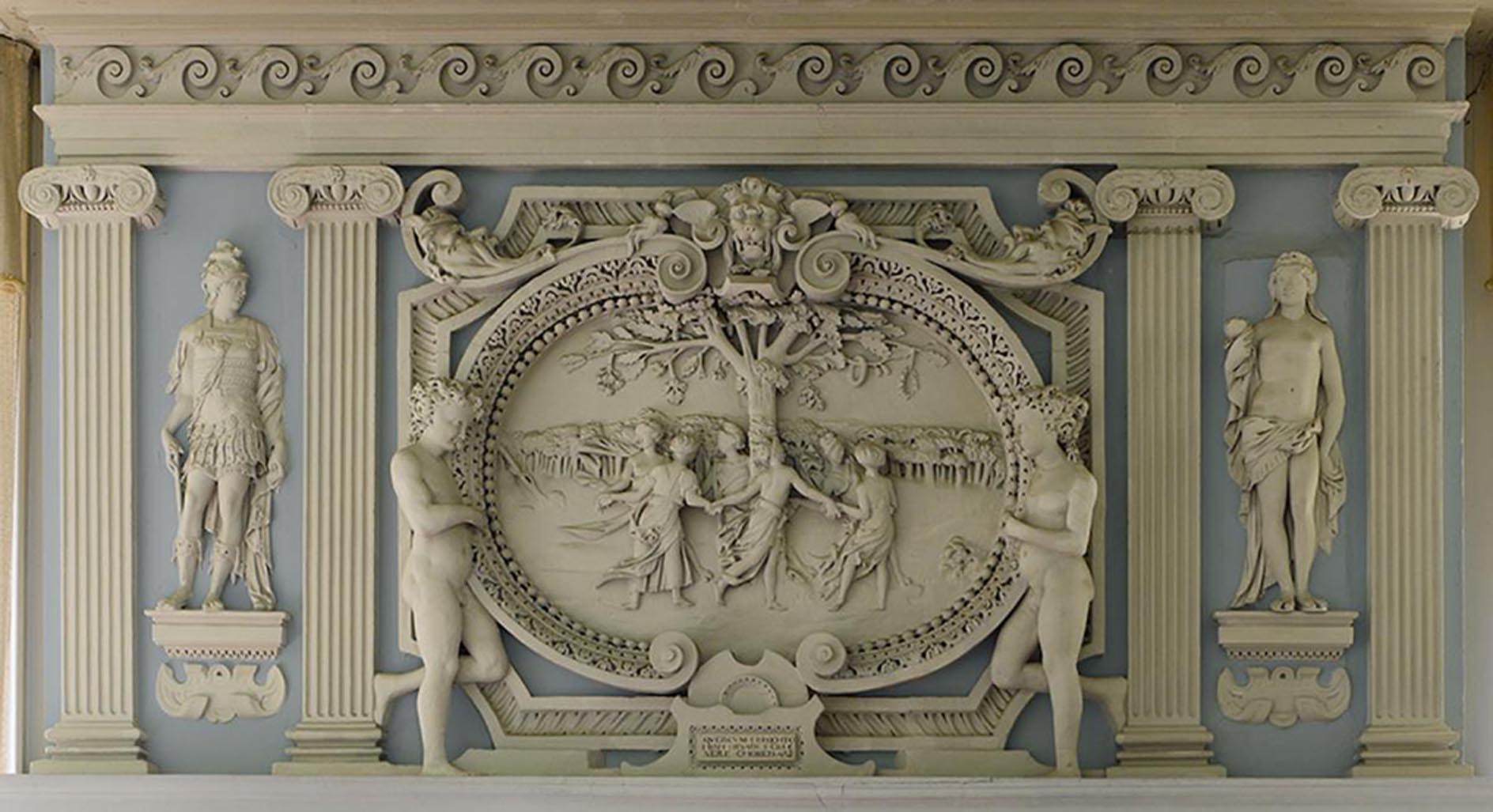

Wainscot kept rooms warm and didn’t preclude the display of tapestry, which could be hung over it where necessary. Panelled ceilings served the same practical purpose and are known to have existed in English domestic interiors from the early 13th century. They had the disadvantage of creating dark rooms, so, from the mid 16th century in England, there developed a tradition of decorative plaster ceilings, the white surfaces reflecting the light (Fig 4). It was particularly popular in galleries, long elevated corridors in which it was possible to walk for exercise and enjoy the view. Bletchingley possessed one of these modern interiors, which was the scene of an exchange cited in the Duke’s treason trial.

The Duke’s most notable residence, according to the survey, was more conventional. In 1521 the ‘manor or castle’ at Thornbury in Gloucestershire (Fig 9) comprised two courts, both of which were in the process of magnificent transformation. Big architectural projects took time and this one had been under way for more than a decade. The inner court incorporated the remains of a pre-existing house—built in ‘old’ and ‘homely’ fashion—and a residential range ‘fully finished with curious works and stately lodging’.

This two-storey range survives and is otherwise known to have comprised two suites of domestic rooms beyond the hall, one for the Duchess below and another for the Duke above. Projecting from the range are two spectacular ‘compass’ windows, a form that would enjoy enormous popularity into the 17th century (Fig 7). No less striking are the massive and intricately carved chimney stacks, a disinctive feature of English buildings that advertised the comfort of the rooms they served. In both details, Thornbury is inspired by the opulent building projects of Henry VII.

The compass windows overlooked ‘a proper garden’, enclosed on its outward sides by a two-storey timber gallery that communicated with the adjacent church (which the Duke splendidly rebuilt as part of the castle’s demesne). We otherwise know that this cloister-like space was planted with geometric patterns termed ‘knots’ by the gardener John Wynde, who was rewarded for his work in 1520. Confusingly, his knots may have depicted knots, a tied length of rope being an emblem of the family; Tudor nobles dusted everything they possessed with marks of ownership. This ‘privy’ garden opened by degree into the landscape.

Next to it was ‘a large and goodly orchard full of young grafts well laden with fruit, many roses and other pleasures’, such as ‘goodly alleys to walk in openly’ and encircling alleys ‘with resting places covered thoroughly with white thorn and hazel’. Around the orchard were enclosing fences and ditches with ‘quickset hedge’ and from it several gates issued into ‘into a goodly park’ beyond with 700 deer. The connection of the house with its garden, orchard and the wider landscape was not a novelty, but it increasingly shaped the design of houses during the 16th century and clearly delighted the surveyor; it sounds as if he visited on a beautiful day.

The Duke’s many residences served as the backdrop to his daily life, which was focused on the institution of his household. Its operation can be inferred from the accounts seized by royal officers and sets of regulations governing other aristocratic households, such as the voluminous statutes drawn up by his brother-in-law, the Earl of Northumberland, in 1512.

Confusingly, the household could vary in size depending on which residence it occupied. It was usually at its largest at Thornbury where, in 1507–08, for example, more than 150 members attended two meals in the castle every day (accompanied by about 70 guests). Not all the Duke’s residences were big enough to accommodate the entire household. In London in the same year, for example, it was less than half that size. For travel, it reduced yet further as a ‘riding’ household.

In all its forms, the household was divided into specialist departments, including the kitchen, stables, chapel and personal companions. From the late 15th century, moreover, and encouraged by the behaviour of Henry VII, who chafed at the public lifestyle expected of an English king, there was an increasing division between the public realm of the great hall and the withdrawing or ‘privy’ accommodation beyond it. In the houses of both noblemen and ecclesiastics (the domestic building traditions of both are almost indivisible), halls remained important as the spaces (Fig 5) in which the bulk of the household received their meals, one of the central benefits of household membership.

Increasingly, senior members of the household began to live more of their lives in the withdrawing apartments beyond the hall. These were figures of real social standing, their service reflecting on the Duke’s high status. At Thornbury, this shift is documented in the arrangements for feasts, where this group sat separately from the rest of the household in the withdrawing room beyond the hall dais.

Meals were governed by complex protocols and places were laid with a spoon and pointed knife only. Food was served in bowls to ‘messes’ or small groups, who generally sat on one side of a table to allow servants access on the other. The Duke himself probably sat alone. On important occasions, food would be played into the room and eaten to music. Medieval and Tudor dining was visually splendid, but conversation cannot have been easy.

In addition to food and an allowance of fuel, members of a great household received measures of cloth for clothing or livery, the colour and quantity again denoting status. It’s from livery that we derive modern academic and judicial gowns, which make the relative status of an individual apparent. Gowns were a clear mark of service often bearing family emblems. That explains why, in 1519, Henry VIII was so enraged to spot a member of the Royal Household wearing the Duke’s livery in his presence. ‘None of his servants,’ he raged, ‘should hang on another man’s sleeve.’

Running households was hugely expensive. The annual expenditure on the provisions of the household for the years ending in September 1518–20 was respectively £2,634, £3,700 and £2,898. In addition, over the same years, £2,414, £2,586 and £4,200 were spent on the wardrobe. At a time when skilled workmen might receive a wage of eight pence a day, these were stupendous sums.

These same accounts list occasional payments that illuminate curious details of daily life. There are rewards for cooks, ‘idiots’ or jesters, harpists, tumblers, singers, poets, waites and players, as well as considerable gambling losses for games of dice, shooting and tennis. These are incongruously interleaved with devotional oblations, plus outlay for food, drink, scholarships and servants’ tips. It’s easy to think of noble life in the past as being serious and comfortless, but the rich have always lived for pleasure and delight.

With the execution of the Duke, the last great medieval inheritance passed into the voracious maw of the Tudor state. The property of the Church would follow by stages over the next three decades. The effects of these changes were surprisingly slow to be felt in the domestic sphere, as we will discover in the next article when the focus turns to the following century.

Ockwells Manor, Berkshire: An insight into the splendours of grand living in 15th-century England

A delightful timber-frame house offers insights into the realities of luxurious 15th-century living and the brutal complexities of Lancastrian politics,

From abbot to artist: The remarkable journey of Abbots Grange, Worcestershire

A house built for the Abbot of Pershore in the 14th century was restored as a studio by an American

The mysteries of Ightham Mote, from its early origins to the skeleton discovered behind a bricked-up door

Ightham Mote is one of the most beautiful medieval houses in Britain. The tale of its murky origins and recent

Llwyn Celyn: One of the most important medieval homes in Britain — yet one where, wonderfully, you can book family holiday

Llwyn Celyn, one of the most important medieval houses in Wales, has been recently restored and dated for the first

Great Chalfield Manor: How this medieval house was loved back to life

In the second of two articles, Clive Aslet reveals how this medieval manor house was loved back to life by

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Burberry, Jess Wheeler and The Courtauld: Everything you need to know about London Craft Week 2025

Burberry, Jess Wheeler and The Courtauld: Everything you need to know about London Craft Week 2025With more than 400 exhibits and events dotted around the capital, and everything from dollshouse's to tutu making, there is something for everyone at the festival, which runs from May 12-18.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Everything you need to know about private jet travel and 10 rules to fly by

Everything you need to know about private jet travel and 10 rules to fly byDespite the monetary and environmental cost, the UK can now claim to be the private jet capital of Europe.

By Simon Mills