‘They knew they were all going through the same hell’: The graffiti of the First World War

Memorials to those lost in the First World War can cloud the fact that each name represents a man’s life. The inscriptions they left behind, however, recall them as individuals, says David Crossland.

Daniel McAlpine, a private in the Highland Light Infantry, was sheltering in a tunnel under the Somme village of Bouzincourt, France, when he pencilled his name, service number, unit, home town of Glasgow and the words ‘Wounded 3 times’ into the soft chalk. It was early 1917 and his battalion had fought in the Battle of the Somme the previous year. The reference to his wounds rings with pride and hope that he had suffered his share of bad luck — and might survive.

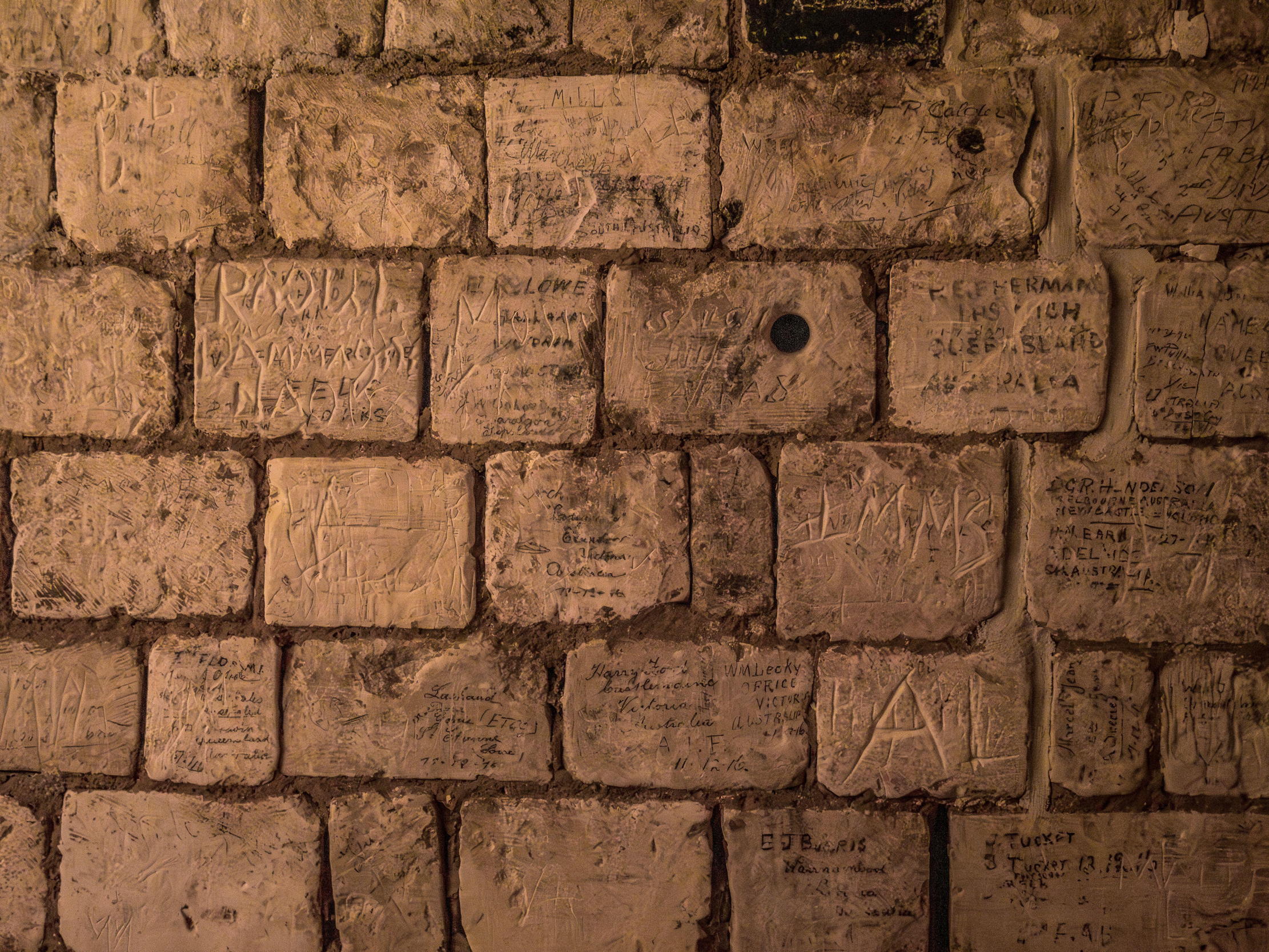

McAlpine’s inscription is among more than 10,000 to have been catalogued on the Western Front, most of them in old limestone quarries underneath the fertile fields of Picardy that witnessed some of the bloodiest battles.

Each such trace tells a story. Five months after McAlpine immortalised himself in Bouzincourt, his Second Battalion was in trenches at Cuinchy, 34 miles to the north. July 16, 1917, was an ordinary day on the front line; no major battle, only the routine of repairing trenches, cleaning weapons and keeping a lookout. The battalion’s war diary for that day stated: ‘Companies carried on as usual supplying working parties to front line Companies at night. Our own and enemy T.M’s fairly active.’

T. M. refers to trench mortar, which could bring death out of the blue. McAlpine, aged 20, wounded three times, was killed on that summer day. Whether it was a T. M., some other shell or a sniper is unclear from the records available. His inscription at Bouzincourt is still legible today, feet below the sleepy village where the silence is broken only by the church bell and the occasional tractor. It is one of 1,000 traces left there by British, Canadian and Australian soldiers.

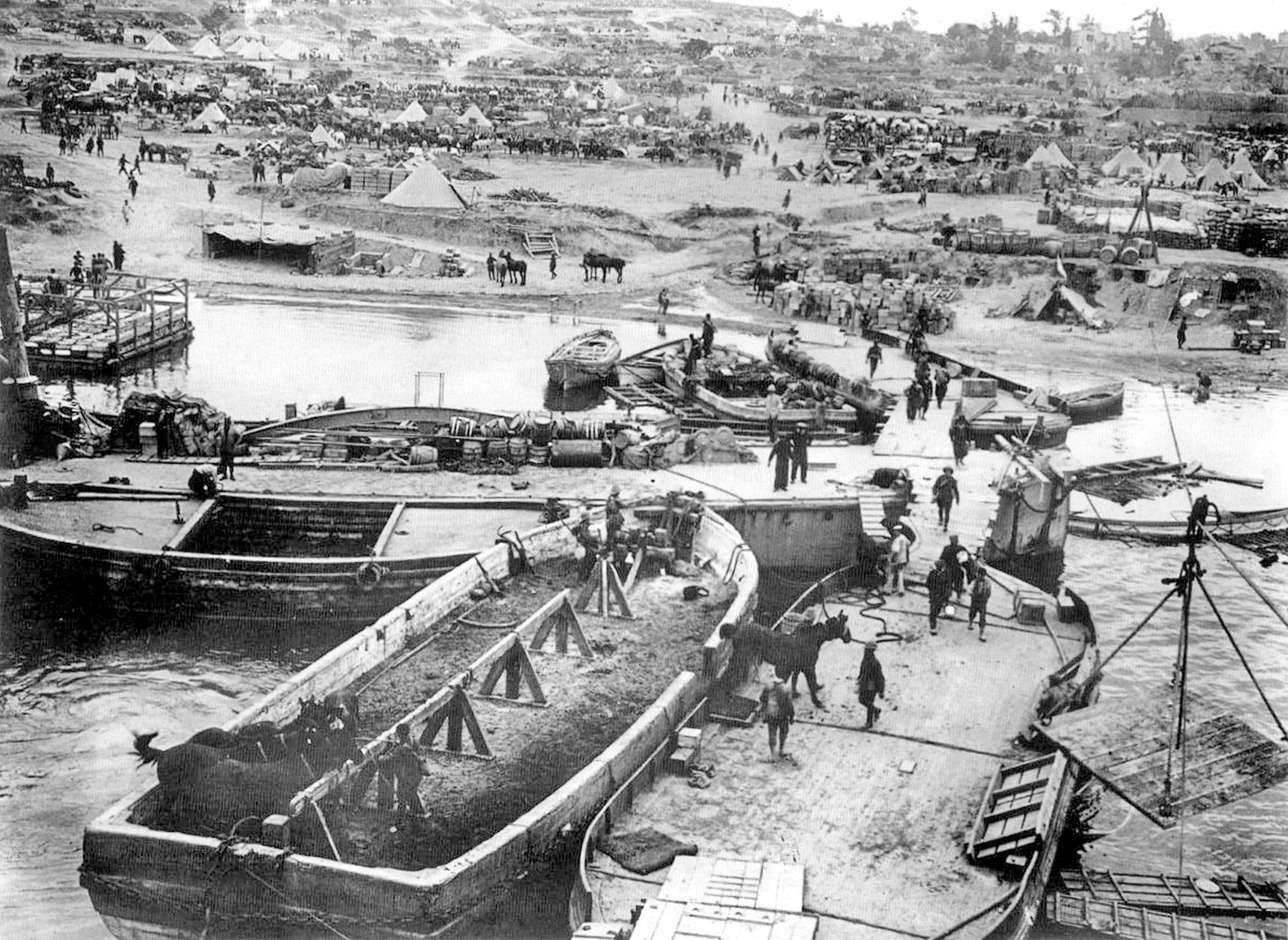

Dug centuries ago, the quarries of Picardy fell into disuse in the 19th century. After the Front stagnated within weeks of the war breaking out, all armies seized these labyrinthine cave networks as shelters, command posts and field hospitals. Down here, the men’s thoughts were free to roam. The soft walls became their canvases.

'‘They shared the fear of death. And they all wanted to show “I was here, I participated in something extraordinary, I did my job”

Today, some of the caves are time-warps strewn with bully-beef tins, boots and shell casings. Their entrances lurk forbiddingly in forests roamed by wild boar. The graffiti they contain is a priceless legacy that is under growing threat. It amounts to direct testimony of how the soldiers experienced and reacted to the war as it was happening — with military pride, a yearning for home and a desire to leave a trace of themselves, aware that it could be their last. Scores of men are known to have been killed within weeks of making inscriptions.

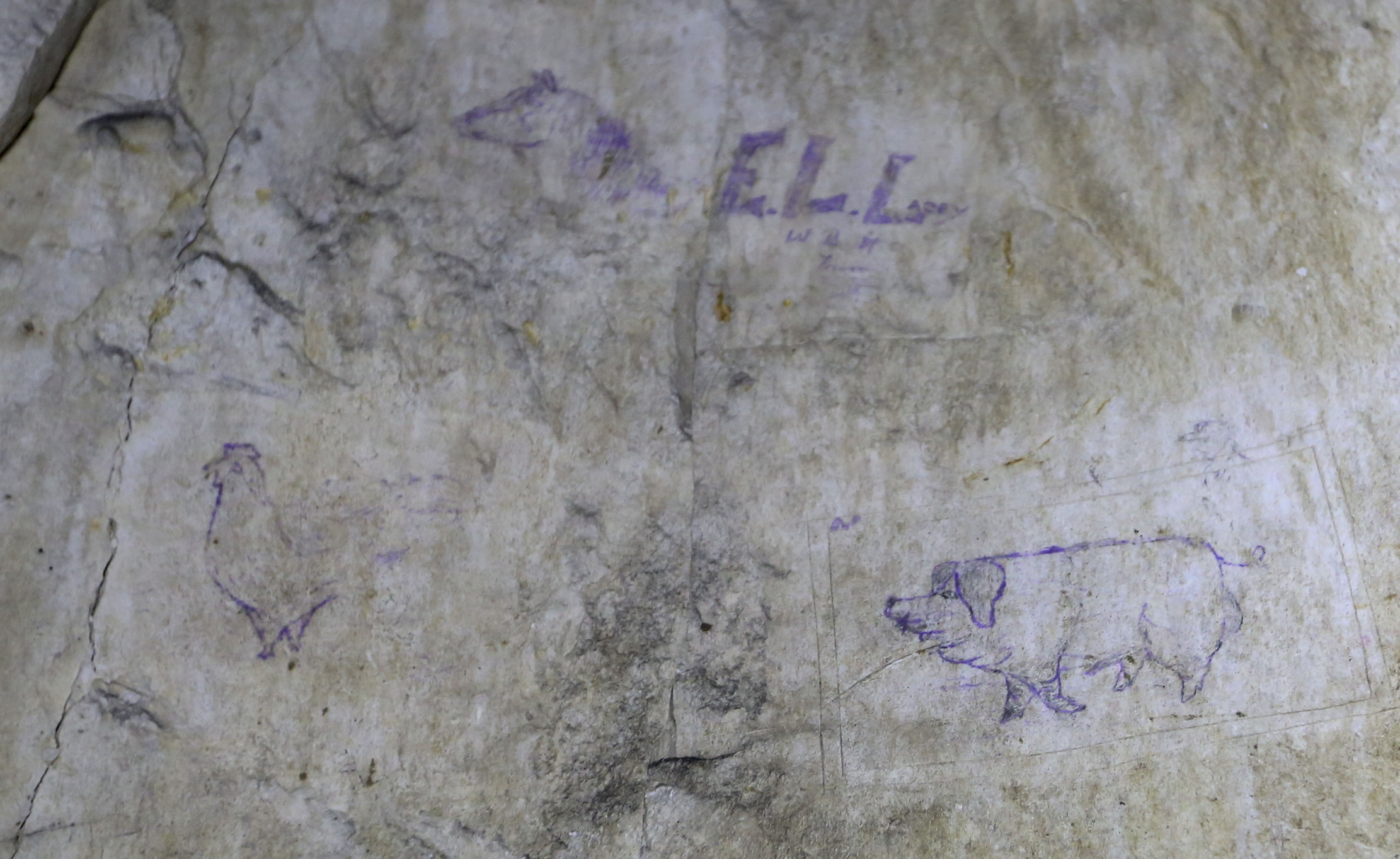

The works include portraits of wives or girlfriends, favourite pets or farm animals back home, poems, patriotic slogans, Christian crosses or national symbols, such as Nelson’s Column, Marianne, the Iron Cross, Canadian maple leaves or Native American profiles with feather headdresses. The full range of emotions is on display. Elaborate drawings of regimental insignia reflect the eagerness of Britain’s newly formed Pals’ Battalions to get into the fight. Later inscriptions such as ‘Hell’ and ‘Jesus Have Mercy on Us’ tell a different story.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The graffiti provides a fresh look at a generation that, more than a century on, tends to be remembered collectively rather than as individuals. Above ground, the giant cemeteries and memorials such as Thiepval and the Menin Gate can obscure the fact that each name stands for a life lived and a dream dreamt.

In a quarry used by the Canadians near Arras, Private Earl Laroy Lacey, the son of an Ontario farmer, drew a chicken, a horse and a pig on the wall. He survived the assault on Vimy Ridge in April 1917, but was struck by a machine-gun bullet and killed on February 23, 1918. His faded drawings still evoke his longing for home and a future in peace.

An inscription under the village of Naours was traced back to the Antarctic explorer Leslie Russell Blake, a peer of Robert Falcon Scott and Sir Ernest Shackleton, who was awarded the Military Cross by George V at Buckingham Palace in June 1917. The Australian lieutenant, a trained surveyor, had the lethal job of creeping into no man’s land and mapping the German lines in preparation for artillery barrages. After being wounded twice and promoted, he could have spent the rest of the war in the safety of staff headquarters, but he preferred to be with his men and was killed 39 days before the Armistice.

Also at Naours, Samuel Meekosha, of 1/6th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, wrote his name in big letters. It was rediscovered in 2015 and traced back to the sergeant whose valour under heavy shellfire near Ypres in 1915 won him the Victoria Cross; he featured in a cigarette-card collection of war heroes.

Other inscriptions record actions, such as a French panel in a cave near the River Oise, marking the spot where the Croix de Guerre was awarded to Col Henry Simpson of the 173rd Brigade of the Royal Artillery, for delivering fire that relieved French troops at Lassigny during Germany’s 1918 Spring Offensive.

Strikingly, the graffiti seldom expresses hatred of the enemy. Instead of defacing each other’s traces, soldiers from opposing armies would write their own inscriptions next to them. ‘They knew they were all going through the same hell,’ noted a French archaeologist.

Today, the more than 400 caves containing war graffiti are at increasing risk from erosion, vandalism and theft. The tunnels beneath Bouzincourt have been closed since 2020, due to a risk of collapse. Dampness has dissolved many of the inscriptions. As a result, these sites have become the focus of intensifying research amid calls for funding to protect them.

Historian Thierry Hardier, France’s leading expert on the graffiti, believes the caves are as worthy of UNESCO World Heritage status as the 139 Western Front cemeteries and memorials that were awarded it in September 2023. ‘The overground sites are already well maintained… whereas the quarries, some of which are exceptional, need investment in gates and security cameras,’ he says. ‘We face a dilemma. We need to highlight the importance of these sites, but we must not attract too many visitors, because that could speed up their deterioration. Many are dangerous, too.’

There are intriguing national differences in the inscriptions. The Allies, far from home, often left their names and even addresses. The French took inspiration from depictions of women on bank notes or coins and also had a predilection for nudes. Their commanders picked out soldiers with a talent for sculptureto adorn the caves with rousing artworks and regimental panels.

The Germans, meanwhile, confined themselves to functional signage, such as ‘To the kitchen’. They left fewer personal inscriptions than the Allies, perhaps because it was verboten by commanders. A common German inscription is the slogan ‘Gott mit uns’ (God with us). The Americans’ graffiti is big and bold, with lettering resembling the font of billboards. It pulsates with the energy of fresh troops and, from today’s perspective, augurs the outcome of the war.

Despite the cultural differences, the graffiti conveys what the combatants had in common. ‘They shared the fear of death. And they all wanted to show “I was here, I participated in something extraordinary, I did my job”,’ says Gilles Chauwin, president of the Chemin des Dames Association that maintains one of the most striking quarries. ‘These inscriptions are like bottles thrown into the sea.’

David Crossland is a journalist and photographer based in Berlin. His book, Whispering Walls: First World War Graffiti, is out now

Curious Questions: When did we start observing a silence in remembrance of the victims of war?

The tradition of holding a two-minute silence to remember those who gave their lives in war dates back to 1919,

An exhibition that brings together the gun that started the First World War, Hemingway's typewriter, Captain Scott's snow goggle and Sgt Pepper's Drum

The gun used to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Hemingway's typewriter and the drum featured on the cover of Sgt Pepper's

The tragic story of George Moor, the 18-year-old who won a Victoria Cross at Gallipoli and survived the Somme, only to die days before the end of the First World War

Second Lieutenant George Moor was a teenager who signed up for service at the outbreak of the First World War

The unique and extraordinary images of the First World War created by Britain's first-ever official war artist

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.