'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar career

Clive Aslet explores the relationship between Sir Edwin Lutyens and perhaps his most important private client, the politician and financier Reginald McKenna.

Of all the front-line British politicians during the First World War, Reginald McKenna is hardly the best known. Yet the year that he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer, in 1915–16, gave him an awesome responsibility, as conflict on a rapidly increasing scale could not have been pursued without money. If he is remembered at all, it is likely to be for his contribution to architecture. He was one of Sir Edwin Lutyens’s most prolific clients, commissioning a townhouse, two country houses and a house for his son, David, and daughter-in-law, Lady Cecilia Keppel, not to mention that great leviathan of commerce, the Midland Bank head office, together with three branch banks, when he was chairman of the Midland from 1919. Naturally, Lutyens loved McReggie, as he called him; he always did his best work for clients he liked.

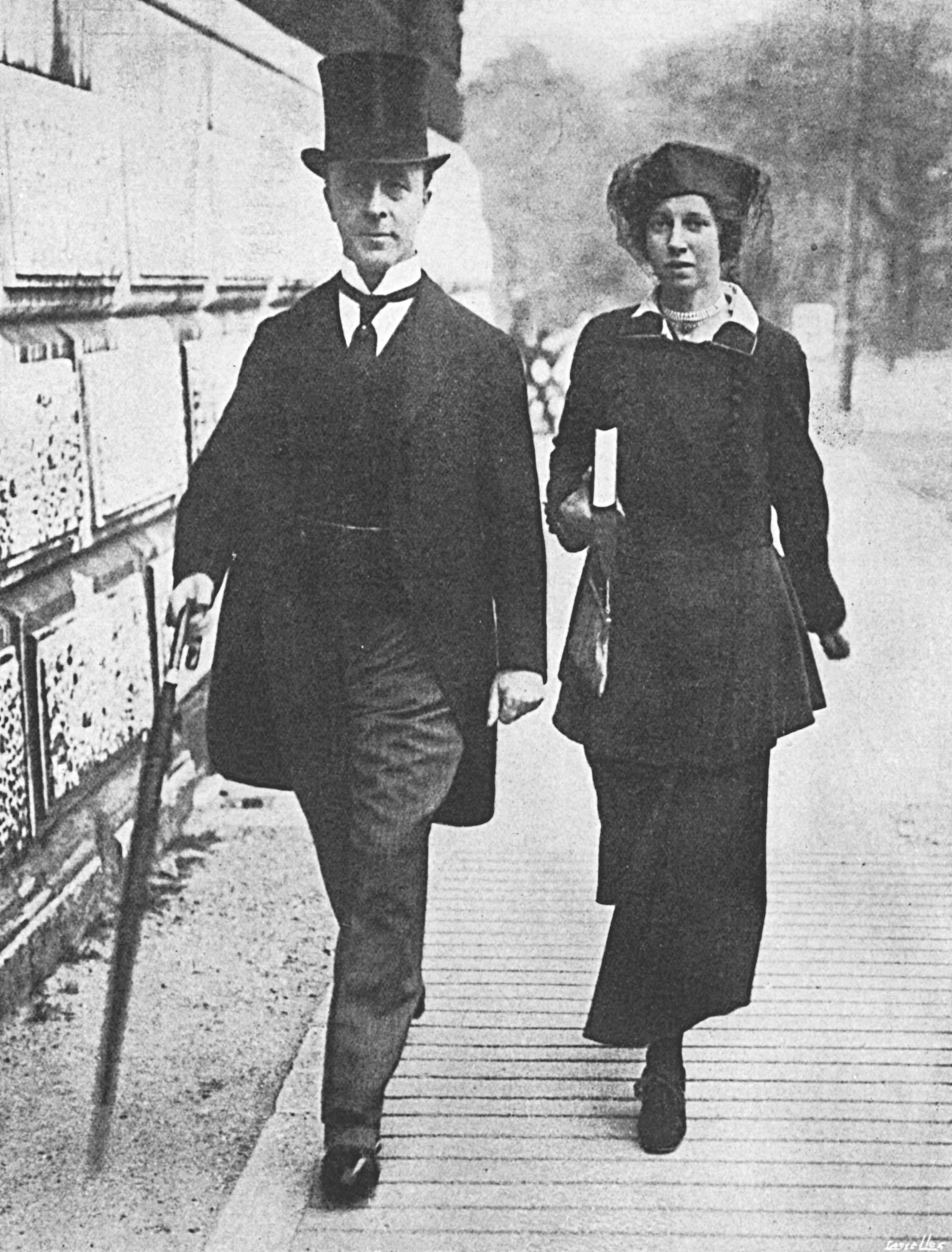

Fig 1: Reginald McKenna and his wife, Pamela.

Architect and client had been born six years apart — McKenna being the elder — in the 1860s. Their childhoods had both been marked by a parental crisis with money. Lutyens’s father, Charles, had largely failed as an animal painter and family money ran into the sands. The McKennas’ financial boat was overturned by a bank crash, as a result of which the family split to save money, Reginald being one of the younger children economising with their mother in France. It would later be noted that he spoke much better French than cabinet colleagues, including H. H. Asquith. Unlike many of the political grandees among whom he moved, McKenna went to King’s College School, then on the Strand — good enough, academically, to get him into Cambridge on a scholarship to read mathematics, but not of the réclame of such great public schools as Eton and Harrow.

At Cambridge, he excelled as an oarsman: according to A History of the Trinity Hall Boat Club, he ‘thought out the whole theory of rowing afresh for himself, being helped not a little by his knowledge of physics’, as well as having a slide, a rigger and part of an oar to practise the necessary movements. It was at Cambridge that politics called with what, to an impecunious young man who had nothing to support him in an unsalaried career, seemed a siren-like voice. On going down, he became a barrister, entering the Commons aged 32 as a Liberal. According to Vanity Fair, he had ‘an air of aggression’, behind which he was ‘earnest and sensitive’. He rose to become First Lord of the Admiralty in 1908, beginning the building of Dreadnoughts after a spy had skated around the harbour at Kiel to see what the Germans were doing.

Fig 3: Mulberry House on St John’s Smith Square, London W1, makes use of grey bricks with red facings.

There was another way in which this was an important year for McKenna. Now in his mid forties, he married Pamela Jekyll, daughter of the soldier and civil servant Sir Herbert Jekyll and niece of Lutyens’s great mentor Gertrude Jekyll. Twenty-five years younger than Reggie, Pamela was lively, very musical and, for a brief time, one of the ‘harem’ (Margot Asquith’s word) of well-born young women whom Asquith liked to bombard with attentions. Inheriting from her mother what his friend the economist John Maynard Keynes called ‘the fairest traditions not of the great but of the middle houses of England’, she created a setting of music and relaxation in which the Chancellor ‘kept the Sabbath, even in times of war, by abstaining from work’.

The match does not seem to have delighted Pamela’s family, who, in the impenetrable jargon of the day, ‘were all rather skiffy coffy’ over it, according to Lutyens. But to Keynes it seemed that McKenna ‘who had been too long a bachelor learnt the tenderness of life’. Pamela was happy, too (Fig 1).

Fig 4: The main staircase in Mulberry House.

It was, of course, she who brought McKenna within Lutyens’s orbit; the Jekyll network proved far more helpful to his career than that of his aristocratic wife, Lady Emily. To Lutyens, anyone who got married needed a house, but the McKennas already had one, courtesy of his position as First Sea Lord. This changed two years later, when McKenna swapped jobs with Churchill to become Home Secretary. It was time to build and build quickly; he bought a site in Smith Square — No 36, later to be called Mulberry House. ‘I do hope he asks me to build for him,’ Lutyens wrote to Emily. ‘Pamela is for me — and the whole Jekyll family.’ If McKenna felt he had been caught, he was not to regret it. He and his solicitor brother Theo were keenly interested in architecture, to the extent of drawing out plans on graph paper (Theo commissioned ‘beautiful models’ of his country-house designs, according to his obituary in The Times). Too much client involvement might have irritated some architects, but Lutyens’s letters were soon opening with ‘My dear McReggie’ — a foretaste of the MacSack and MacNed with which the exotic Lady Sackville and he would later address each other in their strangely infantilising amour.

At a casual glance, Smith Square seems early Georgian, presumably built at the same time as the Church of St John that stands foursquare in the centre, but three sides of it are Edwardian, in an earlier style. Lutyens took his theme from the one terrace to survive from the 1720s, adopting the palette of grey brick with red dressings (Fig 3). Stone blocks form Gibbs surrounds to the ground-floor doors and windows. ‘McKenna thinks my staircase is a miracle,’ Lutyens reported (Fig 4). Pamela was equally excited: ‘I am too lucky!’ she told a friend in the Admiralty after being given the panelling and carving of ‘an immense Georgian room’ for her own drawing room. Alas, little of this interior survived the Art Deco remodelling for Lord Melchett in 1930.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Fig 5: Halnaker House in West Sussex, photographed in about 1938.

‘The whole Jekyll family’ included the Horners at Mells Manor, Somerset, where Lutyens’s champion Frances Horner, Pamela’s aunt, was Sir Herbert’s sister-in-law. McKenna loved the aura of domestic security Mells provided, in contrast to his rackety childhood. The warmth between the McKennas and the Horners can be seen from a letter in the Churchill Archives Centre at Cambridge, with sketches for the equestrian monument in Mells church to the last of the line, Edward, who died at the Battle of Cambrai. Dated July 9, 1918, it shows that Lutyens interested himself in every detail.

Not only did he design the plinth, but he also devised what Alfred Munnings would sculpt. ‘A present day uniform would be better [presumably than armour] but more difficult to achieve wh. makes an attempt more worth while. Do cavalry wear tin hats? Could you get a photo of a man in the 18th Hussars in 1914 war kit?’ Lady Horner must have sent the letter to Reginald and Pamela for an opinion on this emotionally charged project. In the end, Edward was, indeed, shown in modern ‘war kit’, but bare-headed, with the tin hat attached to his saddle. Munnings, a painter more than sculptor, may have been chosen for his knowledge of horses: presumably, it was thought they required special skill (Fig 7).

Fig 6: Lutyens’s sketches of Mells Park, following the fire of October 1917.

Years earlier, Lutyens had helped the Horners revive the Manor, to which they had moved from Mells Park to save money. Mells Park, a handsome 18th-century house, had been let. One blustery night in 1917, it caught fire. The Frome Fire Brigade could not find horses, the Radstock Fire Brigade’s engine got stuck in mud and the house was reduced to a shell.

After the war, McKenna took on a rebuilding lease. An album at the Churchill Archives contains Lutyens’s first sketches for the construction of Park House (Fig 6) and photographs of work in progress. Nothing was kept of the main house beyond a single external wall. This gave Lutyens carte blanche to create an almost new house on the old foundations. He threw a giant order of pilasters across the front, after the manner of Lees Court in Kent (a house associated with Inigo Jones). Green window shutters — a signature of his post-war designs — add a French note.

The quirky arrival is equally brilliant. Guests assume, as they bowl across the park, that the drive is heading straight for the front door, but where would have been the fun in that? Instead, it bends sharply, taking a line to what had been the back of the house. This is where you debouche from the car, to follow a path that leads through a garden service yard, flanked by the arches of cart sheds designed by Sir John Soane (Fig 2). It is not quite true to say that you approach the new house through the ruins of the old, but the result is undeniably a tour de force of the Picturesque. The drawing room contained not one, but two pianos for Pamela and her musical friends, among them the composer Sir Hubert Parry, director of the Royal College of Music.

Fig 7: The Horner monument at Mells, with the horse and officer sculpted by Munnings.

Two more houses were to come. In 1933, No 16 Ingram Avenue in Hampstead, north London, caused an outburst from an affronted Ned, who thought, correctly, that McReggie had gone to another architect. McKenna hastened to explain that John Soutar had only been retained to design this wedding present for his son David because he was on the spot. ‘There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT for me,’ was his emollient reply. The suavity of the entrance front in 2in silver grey and red brick, with a swan-neck pediment and pavilions to enclose the courtyard, shows that the only one ARCHITECT was shown the drawings.

In a reminiscence recorded by the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust in 2002, David McKenna remembered his father drawing schemes on graph paper, which Lutyens corrected. As well as specifying the materials, Lutyens was responsible for placing the house on the site to allow room for a tennis court behind it. It was left to Soutar to make working drawings and obtain planning permission. In 1937, David McKenna and his wife brought Soutar back to make a few alterations, moving the dining room that (in typical Lutyens fashion) had been too far from the kitchen.

As the lease on Park House neared its end, the Mells estate bought it back and the McKennas built another country house, more conveniently located for them in West Sussex. The site was chipped from the Goodwood estate and included the substantial ruins of an old fortified manor house called Halnaker Castle. On September 4, 1935, McKenna wrote to ‘Darling Peeks’ (Pamela) that Ned allowed him to say ‘he is going to make a very pretty “cottage” of it (Fig 5). He agrees that rough-cast whitewashed will probably be the best material’. This was now the Depression and McKenna feared that the first proposal would have to be ‘subject to squeeze’, but a main room of 40ft by 20ft by 20ft, big enough for the two pianos, had to remain, together with an open dining room with open-air bedroom for Pamela above it. The scholarly Alfred Gotch was employed as executive architect, but Lutyens was consulted about every detail; ‘would you agree to lengthening west windows halnaker music room giving lovely view and sun’ reads a telegraph that pursued him to his state room on SS Viceroy of India.

How could McKenna afford all these houses? Because the Midland was then the biggest bank in the world. For Lutyens, this opened the way to some of the most splendid commissions of his career, as we will discover in next week's article.

-

'Fences have blocked wildlife corridors, causing the wildebeest migration to collapse from 140,000 individuals to fewer than 15,000': Is the opening of the Ritz-Carlton in Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve a cause for celebration or concern?

'Fences have blocked wildlife corridors, causing the wildebeest migration to collapse from 140,000 individuals to fewer than 15,000': Is the opening of the Ritz-Carlton in Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve a cause for celebration or concern?In Kenya's iconic Masai Mara region tourism is an important and necessary part of the economy, but the arrival os several large hotel groups — including Ritz-Carlton — have some on edge.

-

‘I get all twitchy when I see people wearing something that really doesn’t belong’: A watch for every summer occasion

‘I get all twitchy when I see people wearing something that really doesn’t belong’: A watch for every summer occasionThere’s a watch for every social summer occasion, from the Mediterranean to muddy festivals. Chris Hall selects some of his favourites.

-

‘It has been destroyed beyond repair, not by the effect of gunfire, but by a deliberate act of vandalism’: Britain’s long lost great houses that live on only inside the Country Life archive

‘It has been destroyed beyond repair, not by the effect of gunfire, but by a deliberate act of vandalism’: Britain’s long lost great houses that live on only inside the Country Life archiveIn the wake of the First and Second World Wars, some of Britain’s greatest houses were lost forever — to extinct familial lines, financial woes, neglect, vandalism and tragic accidents. Thankfully, plenty are preserved — in photographic form at least — for eternity, inside the Country Life archive.

-

'This is how the countryside looked to Gilbert White, to Thomas Hardy, even to Shakespeare and Chaucer': The forgotten corner of the world where King Charles has poured his energy into preserving an all-but-extinct way of life

'This is how the countryside looked to Gilbert White, to Thomas Hardy, even to Shakespeare and Chaucer': The forgotten corner of the world where King Charles has poured his energy into preserving an all-but-extinct way of lifeThe historic buildings of a Transylvanian settlement have been restored and preserved with the help of several foundations and backed by The King’s personal enthusiasm. Jeremy Musson reports on this remarkable place; photographs by Paul Highnam.

-

From the Country Life archive: Yes, that is a Moon Transmitter on London's South Bank

From the Country Life archive: Yes, that is a Moon Transmitter on London's South BankEvery Monday, Melanie Bryan, delves into the hidden depths of Country Life's extraordinary archive to bring you a long-forgotten story, photograph or advert.

-

'I have lost a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed': Inside Jane Austen's Winchester home, the house where she penned her final words and drew her final breath

'I have lost a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed': Inside Jane Austen's Winchester home, the house where she penned her final words and drew her final breathJane Austen spent the last days of her life in rented lodgings in Winchester, Hampshire. Adam Rattray describes the remarkable recent discoveries made about the house in which she died.

-

Winchester: The ancient city of kings and saints that's one of 21st century Britain's happiest places to live

Winchester: The ancient city of kings and saints that's one of 21st century Britain's happiest places to liveKings, cobbles, secrets, superstition and literary fire power–Winchester has had it all in spades for centuries and is as desirable now as it ever was, says Jason Goodwin.

-

The Old House, Dorset: There's beauty up above

The Old House, Dorset: There's beauty up aboveA series of new plasterwork ceilings, collaboratively designed with the creating artist, has transformed the interiors of The Old House, Dorset, the home of Charles and Jane Montanaro. Jeremy Musson explains more; photographs by Paul Highnam.

-

From the Country Life archive: The Maori meeting house in leafy Surrey

From the Country Life archive: The Maori meeting house in leafy SurreyEvery Monday, Melanie Bryan, delves into the hidden depths of Country Life's extraordinary archive to bring you a long-forgotten story, photograph or advert.

-

Stowe Hall and the renaissance of the country house

Stowe Hall and the renaissance of the country houseIn 1975, the end seemed nigh for the great country houses of Britain, but, 50 years on, our built heritage has exceeded expectation and undergone a remarkable revival, John Goodall writes.