Remembering the fallen: The world’s war memorials

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission celebrates its centenary this year. Gavin Stamp contextualises its work by looking at the way in which other nations commemorated their dead.

The Imperial – today, the Commonwealth – War Graves Commission was established a century ago this year. The struggle of its founder, Sir Fabian Ware, to give dignified burial to the First World War dead of the British Empire is now well known. So too is the success of the Commission in creating war cemeteries and Memorials to the Missing of a high architectural standard and of great and serene beauty by employing some of the best architects in the country – above all Sir Edwin Lutyens.

What is rather less well known – at least, in insular Britain – is the way in which the other fighting powers responded to the challenge of burying and commemorating their own victims of mass industrialised slaughter. Comparisons are instructive.

No other war cemeteries approach the British ones in terms of the care taken over horticulture and landscaping, but the wisdom of Ware and the Commission in the policies they adopted is particularly evident in the design of the standard British headstone. It was decided that all individual graves should be marked by an identical secular headstone, regardless of the rank, religion or race of the casualty.

This produced much controversy in Britain, with many grieving relatives wanting the comfort of the Christian cross. The Commission, however, recognised that Jews, Muslims, Hindus and men of no religion had also been fed into the slaughter. Eventually, a compromise was reached in that a Cross of Sacrifice was also raised in most British war cemeteries.

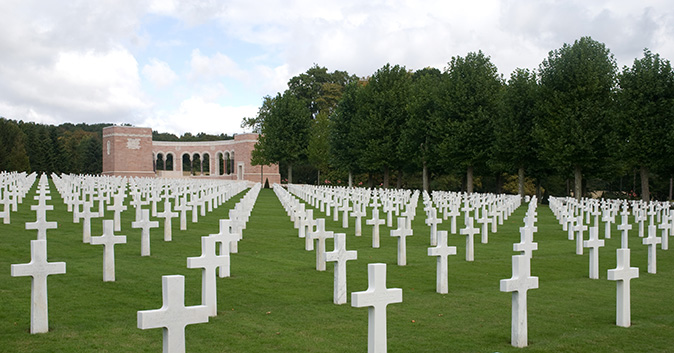

In contrast, France, Germany and the USA placed a cross over individual graves, with the result that the regular lines of headstones are broken by the occasional Star of David or Islamic ogee-arch shape, which can seem a painful reminder of cultural diversity and discord.

Another significant difference in policy between Britain and other nations was that it was decided to leave most casualties near where they fell and were buried. In consequence, there are few large British cemeteries of the First World War. What now seems appalling about them is not their size, but their number, for there are more than 900 British war cemeteries along the line of the Western Front in France and Belgium. They vary in size and, subtly, in their architecture within the accepted Classical tradition. Other nations, in contrast, exhumed the many, many bodies after the hostilities and concentrated them in huge cemeteries or in mass graves.

It is, perhaps, too little appreciated how great were the problems faced by France in 1918. The country was impoverished by four years of war, which had drained it of both resources and men – France’s death toll, at 1.4 million, was half as much again as that of the British Empire. Furthermore, much of northern France was devastated, churned up by years of shelling and with the ground still full of unexploded shells and bombs.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

No wonder, therefore (as it was reported in 1926), that ‘the French authorities were disquieted by the number and scale of the Memorials that the Commission proposed to erect in France’ and by the ‘grandiose’ monuments the Americans and the Canadians wished to build on French soil. Ware was sympathetic to France’s disquiet and predicament and, in consequence, reduced the number of the proposed Monuments to the Missing (Lutyens’ extraordinary three-dimensional arch designed for St Quentin was then moved to Thiepval on the Somme).

France’s policy was to rebury her identified and unidentified dead in large nécro-poles nationales, laid out by the Service des Sépultures de Guerre after 1919. Many are huge, bleak and featureless, with rows and rows of concrete crosses bearing the names of the dead on stamped tinplate labels. The largest of these, at Notre-Dame de Lorette near Arras, where a pilgrimage chapel once stood, is more rewarding architecturally.

Some 40,000 men were reburied here, with the unidentified placed in an ossuary below a tall lantern tower and 24,000 in marked graves. In the centre is a basilica, in a modernised Byzanto-Romanesque style, built in 1921–27 and designed by Louis-Marie Cordonnier and his son Jacques, the architects of the basilica at Lisieux. It is a disconcertingly conservative building for its time, suggesting perhaps that, in the throes of a national trauma, many French architects did not know quite how to respond to such a melancholy, terrible challenge.

A rather different solution was arrived at further east, at the ‘mincing machine’ of Verdun, where, over a period of almost a year, 250,000 men, on both sides, had perished in a ghastly war of attrition. The principal architectural consequence here was the huge ossuary at Douaumont, overlooking a nécro-pole nationale with its 15,000 graves. This barrel-vaulted structure, with curved ends and surmounted by a lighthouse tower, has sometimes been compared to a gun-emplacement, a fort or even a submarine.

Commissioned not by the state, but by a committee of veterans and others convened by the Bishop of Verdun, it was built in 1920–32. Its purpose is horribly simple: in it are deposited the bones of 130,000 unidentified victims of industrialised slaughter, with the indistinguishable remains of French and German soldiers inevitably mixed.

Tinged by the Art Deco of the 1920s, this novel if sinister structure was designed by Léon Azéma, Max Edrei and Jacques Hardy (Azéma was later one of the designers of the Palais de Chaillot in Paris). It is difficult to categorise it stylistically. For Jonathan Meades, Douaumont is ‘shockingly inappropriate… a frivolous mistake’ because of the use of a style that was essentially theatrical. However, it does represent a brave attempt to use a new, modern style for a terrible purpose on an unprecedented scale.

The mainstream, French Classical tradition is hardly evident in the French cemeteries, but it was maintained by contemporary American architects, so many of whom had studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Several of those commissioned by the American Battle Monuments Commission – established in 1923 to deal with the consequences of the USA’s late entry into the conflict – had been trained in Paris and the most distinguished of them, Paul Philippe Cret, was French by birth.

Cret, who had emigrated to Philadelphia, was responsible for the huge Aisne-Marne American Monument at Château-Thierry, commissioned in 1926, a double colonnade of square fluted piers in that stripped Classical manner that would become the true international civic style of the 1930s.

The Meuse-Argonne Monument on the Butte de Montfauçon, a colossal Greek Doric column, is another overweening Beaux-Arts Classical monument, the work of John Russell Pope, the architect of the National Gallery and the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, DC (and the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum).

As for the American war cemeteries themselves, they are perhaps embarrassingly lavish and well appointed compared with those of the French nearby. The cross gravestones in these large, formally laid-out gardens, are of white marble, not concrete, and the memorial chapels were equally expensive and impressive. Sometimes Romanesque rather than Classical in style, these were designed by a range of architects including A. L. Harmon, the New York skyscraper designer; Louis Ayres, who was responsible for several piles in the Federal Triangle in Washington; and Ralph Adams Cram, the Bostonian Anglophile Gothicist.

Italy, which also entered the war later, commemorated her dead in a manner quite unlike that adopted by any other nation. Thanks, in part, to the callous incompetence of the commander-in-chief, Cadorna, the ferocious, avaricious campaign Italy waged against the Austro-Hungarian empire on the mountainous fringes of the Veneto produced huge casualties, some 651,000 in total. The Commissariato Generale Onoranze Caduti in Guerra was founded in 1919, but, owing to economic exhaustion and political instability, little was done until after Mussolini’s Fascist government took power in 1922.

Eventually, it was decided to rebury most of the dead in huge monumental ossuaries, often with a chapel or a tempio-sacrario, which were intended as pilgrimage sites and to encourage a patriotic cult of the dead. Little known outside Italy, these are extraordinary buildings, austere and monumental, and several of the sites were conceived as ‘archi-scultura’ as much landscape as architecture.

Two, in particular, were created by the partnership of the architect Giovanni Greppi and the sculptor Giannino Castiglione. One, Redipuglia in Gorizia province, became the national site of mourning: a giant staircase or sequence of terraces containing the bones of some 100,200 men; the other, on Monte Grappa, some 5,800ft above sea level at Treviso, has a conical terraced ossuary-cum-chapel containing the bones of 12,600 Italian soldiers at the end of a mountain-top axial path lined with free-standing plinths bearing the names of battles. For all their Fascist associations, these sacraria are some of the most original and remarkable structures of their time to be found anywhere.

Finally, there are the memorials of Germany, so many of whose two million dead lay, like those of Britain, in foreign lands – if for rather different reasons. At Quero in the Piave valley, there is a dark stone castle-like ossuary, tough and yet beautifully detailed, containing the bodies of German and Austro-Hungarian troops, which is very different in style and mood from both the grand Italian ossuaries and the nearby British cemeteries in the mountains designed by Sir Robert Lorimer.

Built in 1936–39, it is an example of the Totenburgen or fortresses of the dead designed by Robert Tischler, chief architect of the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge until his death in 1959.

The Volksbund was founded in 1919 and faced the challenging task of dealing with the governments of nations Imperial Germany had invaded. France declined to let the Germans build memorials on her soil, only to create concentrated cemeteries; Belgium was more accommodating. At the Soldatenfriedhof at Langemarck, north of Ypres, Tischler was able to design an impressive dark-red sandstone lodge in a rugged Arts-and-Crafts manner. Behind this is the Kameradengrab, a mass grave containing some 25,000 bodies, surrounded by bronze stele bearing names. Beyond are the graves of a further 10,000 dead.

Originally, the graves in such cemeteries were marked by wooden crosses; more recently, these have been replaced by steel, Maltese crosses or square slabs of grey granite.

Surrounded by oak trees to give a distinctive Teutonic character, Langemarck is a dark place, the last resting place of the thousands killed in the first German assault on Ypres in 1914. This was the so-called ‘Massacre of the Innocents’ as so many were young volunteers and students. Further north near Dixmude is the German cemetery at Vladslo, where bodies were concentrated after the Second World War. Here is one of the great works of art that resulted from the First: two poignant sculptures of the Trauernden Elternpaares – the Mourning Parents – by that courageous artist, Käthe Kollwitz. They overlook a sea of flat granite squares, under each of which lie eight bodies, including that of her own son, killed in 1914.

The figures were originally installed in the German cemetery at Roggeveld, since removed. Kollwitz was present when they were first set up in 1932 and she wrote in her diary: ‘The British and Belgian cemeteries seem brighter, in a certain sense more cheerful and cosy, more familiar than the German cemeteries. I prefer the German ones. The war was not a pleasant affair; it isn’t seemly to prettify with flowers the mass deaths of all these young men. A war cemetery ought to be sombre.’

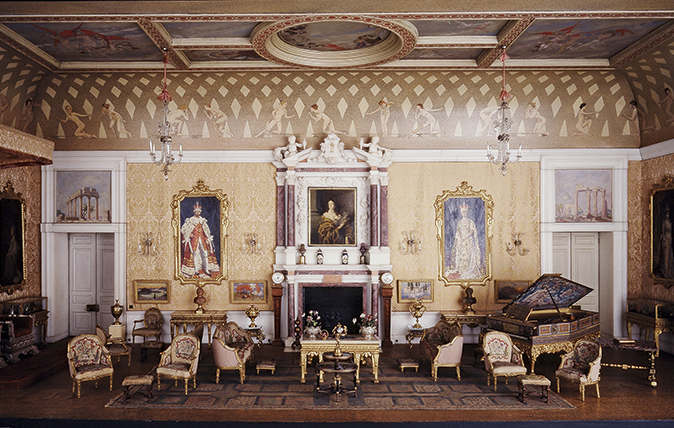

A doll's house fit for a queen: How Lutyens created a Lilliput for Queen Mary

A miniature palace designed by Lutyens and promoted by Country Life offers a fascinating perspective on the 1920s, as Gavin

Alexander 'Greek' Thomson: Glasgow's visionary architect

As we celebrate the bicentenary of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, Gavin Stamp considers the remarkable way in which he adapted principles

The saving of Mount Grace Priory: A ruin revived in Arts-and-Crafts style

The saving of Mount Grace Priory in North Yorkshire is a fascinating tale of far-sightedness, persistence and determination. Gavin Stamp