The Tudor Great Chamber at Gilling Castle, and the bizarre tale of its salvation

John Goodall looks at the Tudor great chamber of Gilling Castle, North Yorkshire, and the bizarre story of how this superb interior was lost and restored. Photographs by Paul Highnam. Photographs by Paul Highnam for the Country Life Picture Library.

If architectural proof were ever required that miracles can happen, the Great Chamber of Gilling Castle could surely be cited as evidence. Walking through the 18th-century hall — described last week — the modern visitor steps into one of the most completely preserved Elizabethan interiors on the grand scale in Britain; an easy match for the splendours of the long gallery at Haddon or the great chamber at Hardwick.

This room was the creation of a wealthy gentleman, Sir William Fairfax, whose great- grandfather had asserted ownership of the castle in 1492. He served with distinction as a soldier in Elizabeth I’s Scottish wars and was knighted at Berwick in 1560, 11 years before succeeding to his estates in 1571. Despite being suspected of Catholic sympathies, he went on to be appointed sheriff of the county for 1577–78. The decoration of the great chamber makes it clear that he was fascinated by heraldry and a list of his books (or possibly those belonging to his son) reveals a library of works in Latin, French and English, including history, politics, theology, topography and literature.

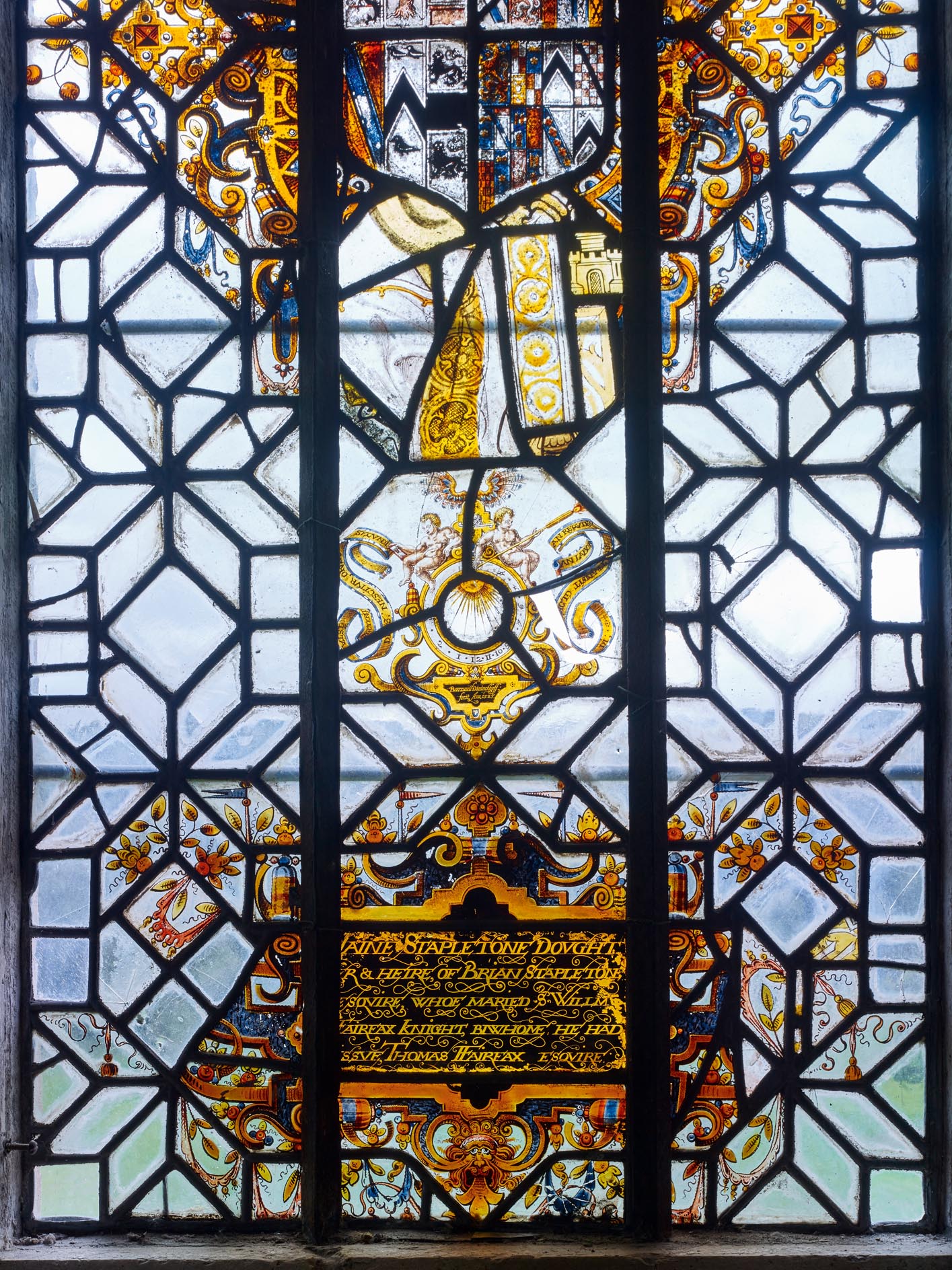

We also know who designed the great chamber for Sir William and not because his name is incidentally recorded in a building account. Uniquely, the room is signed: prominently located to the bottom right of the window that commands the room is a glass sundial and in the frame is written ‘Bærnard Dininckhoff fecit 1585’ (Fig 1). Bernard was a versatile professional of central European origin who was described as a glazier when he was admitted as a freeman of York in 1585–86. He is otherwise known to have worked as a surveyor, garden designer, builder and architect and is likely, therefore, to have overseen every aspect of the work here.

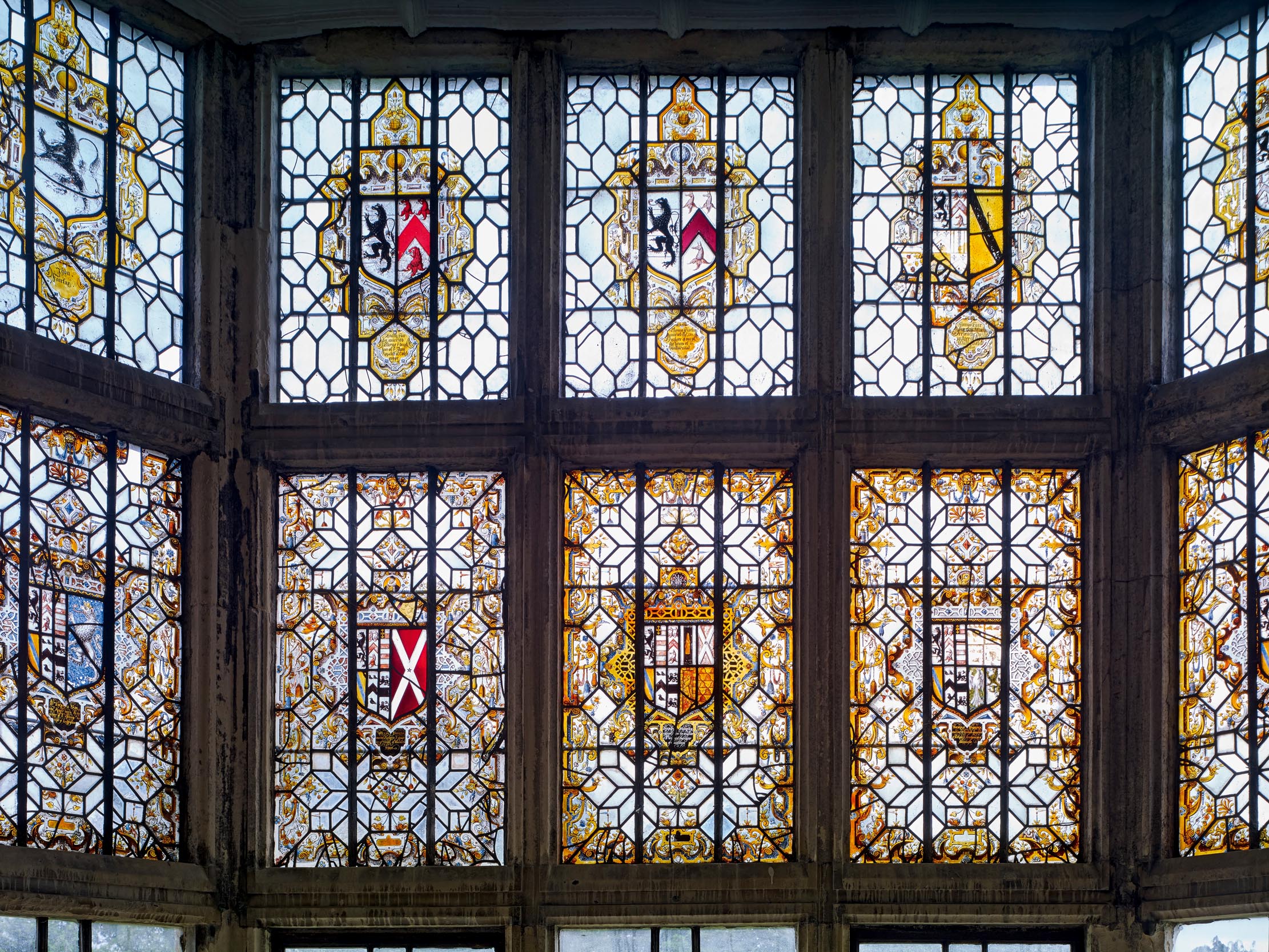

The miracle of the great chamber’s preservation lies partly in its completeness — panelling, painted decoration, stained glass and plasterwork, all of the highest quality (Fig 2). It is also apparent, however, in its repeated escapes from mutilation. The fittings enjoyed their first important reprieve during the early 18th century, when Charles, 9th Viscount Fairfax, whom we encountered last week, a patron whose aesthetic tastes manifestly lay in the world of the Roman Baroque, chose to preserve it as a principal chamber of his fashionable new seat. Only the doors to the room were modernised; there could be no firmer proof of Georgian admiration.

Then, in the early 20th century, at the very moment when buildings such as Haddon and Hardwick in Derbyshire basked in high fashion and were being carefully managed as family heirlooms, one owner of Gilling decided to cash in on the market for period interiors and put the castle and the great chamber on the market independently in 1929. The sale was noticed with studied neutrality by Country Life, which expressed the hope that they might go to a British museum.

It could reflect the stigma attached to the dismemberment of this manifestly important room that the sale failed first time around. The following year, a purchaser did emerge, paying the astonishing sum of about £23,000 for it (with the interior of the 18th-century gallery from the south wing by Cortese illustrated last week thrown in). In late August 1930, the entire room, apart from the ceiling, was hurriedly stripped out and packed up.

In the process of removal, one very significant discovery was made. Underneath the panelling in the upper register of the north wall was revealed a mid-16th-century wall painting. This was executed in grisaille and was reputedly ornamented with the same shields as appear on the fireplace. Its appearance is most fully recorded in an article in the Archaeological Journal, 92 (1935). The fireplace arms (Fig 3) illustrate the marriages of Sir William’s four sisters, so this painted scheme — which presumably still survives — can only narrowly predate Dininckhoff’s work.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The new owner of the great-chamber fittings was the American publishing tycoon William Randolf Hearst, a collector inured to controversy. He seems to have intended his purchase for St Donat’s Castle, Devon, which he furnished magpie-like with some of the finest historic fittings that money could buy (although some newspapers mistakenly reported his intention to take it to America). In the event, however, the packing cases got no further than London. There, they survived the Blitz, but were redistributed between different stores and, following Hearst’s death in 1951, were purchased, unopened, from his executors by the dealer Mallett.

Gilling Castle, meanwhile, had been bought in 1929 — for about half of what the panelling cost — by Ampleforth Abbey as a prep school. Since that time, the great chamber had been in use as a refectory and, in 1936, its interior was made good with oak panelling at a total cost of £147 by Robert Thompson of Kilburn, the ‘Mouseman’. His workshop also supplied over time the tables and chairs that dignify the room today (Fig 5). The abbot was offered the Tudor panelling for £6,000 and set in motion a public campaign, managed by Fr James Forbes, to raise the money. They worked against time with several alternative offers on the table, including one from Mr Butlin to purchase the fittings for the billiard room of his holiday camp at Filey.

The campaign proved successful, thanks to the support of the York Elizabethan Society, which was specially founded to support the cause, and an 11th-hour, closing gift of £2,230 from the Pilgrim Trust. It’s important to add that — according to Hugh Murray’s excellent study of the room in the St Laurence Papers (1996) — the first subscription received was £100 from Thompson himself, given on condition that he could reinstall the panelling.

When the first consignment of packing cases duly arrived on the last day of the summer term 1952 and were unloaded with the help of lifting gear borrowed from a local RAF station, a lot of material was discovered to be missing. An exhaustive further search of London storehouses, however, eventually revealed all but one 10in section of panelling border. The glass was reinstalled by the Northumbria Stained Glass Studio, New-castle, according to its former arrangement as described by John Bilson in an exemplary antiquarian article for the Yorkshire Archaeological Journal (1907).

At the start of the school year, in the autumn of 1953, therefore, the great chamber stood renewed. Here, it confronted generations of prep-school children as they ate their meals and fascinated at least one (this article’s author). Cortese’s gallery, meanwhile, went to the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, Co Durham, where elements of it are on permanent display.

Grand medieval domestic interiors were usually hung with fabrics or tapestry to provide warmth and colour, but, during the 16th century, English patrons increasingly adopted ornamental wainscotting instead. The great chamber illustrates this change in taste, with panelling extending across the lower register of the wall beneath a deep cornice. As befits the most expensive interiors, it is densely framed and intricately carved. In addition, it makes prolific use of marquetry inlay, using pear, holly and ebony wood: there are geometric patterns in the centre of each panel and three types of flower in the angles around it.

Marquetry has long been used to ornament luxury wooden objects, as, for example, in the ‘purfling’ applied to musical instruments. This scale of decoration enjoyed a relatively short period of fashion in England in the last quarter of the 16th century; the closest comparable work is found in the Inlaid Chamber, Sizergh Castle, Cumbria, which must be by the same workshop and can be dated between 1573–85. Curiously, it is a room that has also recently come home (Country Life, June 22, 2000).

To accommodate the windows tidily, there are three tiers of panelling, the lowest of which runs unbroken under the sills. The emphatic grids of the walls and windows reflect the aesthetic of the late-Gothic, Perpendicular style. So, too, the high ratio of window to wall and the spectacular form of the ceiling as a spreading vault with pendants (Fig 7). The ceilings of the window recesses are treated with plaster decoration that finds parallel at nearby Helmsley Castle in a room with an inlaid fireplace dated 1582.

The Gilling great chamber is arranged after late-medieval form with a ‘high’ end, lit to one side by a projecting window or oriel, and a ‘low’ end directly connected by a spiral stair to the kitchens beneath. It is significant that neither of the two early inventories of the house in 1594–95 and 1624 make mention of a hall, so this space was the principal interior for entertainment. It was consequently furnished in the 1590s with a large and small table, 28 stools, a chair and two cupboards, all draped or covered in green silk. Opening from it, probably through the door next to the kitchen stair, was a dining room.

In the frieze over these doors are depicted a mixed consort of musicians. They should be understood as variously playing food into the great chamber for festivities (as it came up from the kitchen) or greeting guests as they retired into the dining room for a private meal. The musicians sit against a trellis on greensward, the colour presumably intended to echo the colour of the room’s fabrics (Fig 4).

The rest of the cornice is decorated with a huge display of the arms of all the gentry families of Yorkshire organised by the administrative and taxation unit of the Wapentake (or ‘hundred’). They hang on trees, each one clearly labelled, in a landscape filled with flowers and beasts. The Wapentakes of the North, East and West Ridings are each grouped together. There existed in the castle a ‘register of all the gentlemen’s arms in the great chamber’, more than 400 in all, of which several manuscript copies are known.

Presenting coats of arms on trees against a background of ‘verdure’ has its origins in late-medieval decoration (in tapestry and wall painting, as in the 15th-century decoration of Belsay Castle, Northumbria). This encyclopaedic display, however, possibly imitates the lost decoration created by Lord Burghley in the so-called Green Gallery at his palatial residence at Theobalds, Hertfordshire. It was completed by 1583 and displayed the arms of each county in the kingdom on 52 trees.

The windows of the room are likewise filled with heraldry (Fig 6), arranged to underline the spatial hierarchy of the room. In the bay window is displayed the ancestry of Sir William and, in the window to its right, that of his wife. The third window must be a late addition; it celebrates the marriage of their son, Thomas, to Catherine Constable of Burton Constable, licensed in 1594.

The school at Gilling Castle closed in 2020 and the photographs taken to illustrate this article were taken in 2018. It’s not presently clear what the future holds for this building or this exceptional interior.

Credit: Strutt & Parker

A historic Scottish castle, complete with battlements, a loch and its very own ghost

Built by Mary Caroline, Duchess of Sutherland, to spite her husband's family, Carbisdale Castle has it all, from royal connections

Château de Lassay: The castle of Bluebeard’s widow

This magnificent French castle has a remarkably colourful history, as Desmond Seward explains.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'Minette Batters explains why she's taken a job at Defra, and bemoans the closure of the Sustainable Farming Incentive.

By Minette Batters Published

-

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the world

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the worldWhere else on Earth can you find more than 752,000 acres of splendid isolation? Words and pictures by Luke Abrahams.

By Luke Abrahams Published