The tale of the fire that turned Cowdray's ancient castle to ruins, the treasure hunters who made it worse, and how what was left was saved

Cowdray House was once one of the finest buildings in England, with Queen Elizabeth I herself coming to stay. Yet the fascinating history of its decline and fall is perhaps even more intriguing than its rise to prominence.

Every Tuesday, we look back at something from Country Life's peerless architecture archives. Sometimes we re-run an old piece in its entirety; other times, we unearth unpublished images of places we've studied in the past. And sometimes we glimpse a building at various times in its history to appreciate the snapshots that the magazine's 127-year history provides.

Often, the houses, we look back at have evolved in the magazine's history, but not in this case. Cowdray House — sometimes referred to as Cowdray Castle — is a ruin now as it was then, but the tale of how it ended up in this condition is fascinating.

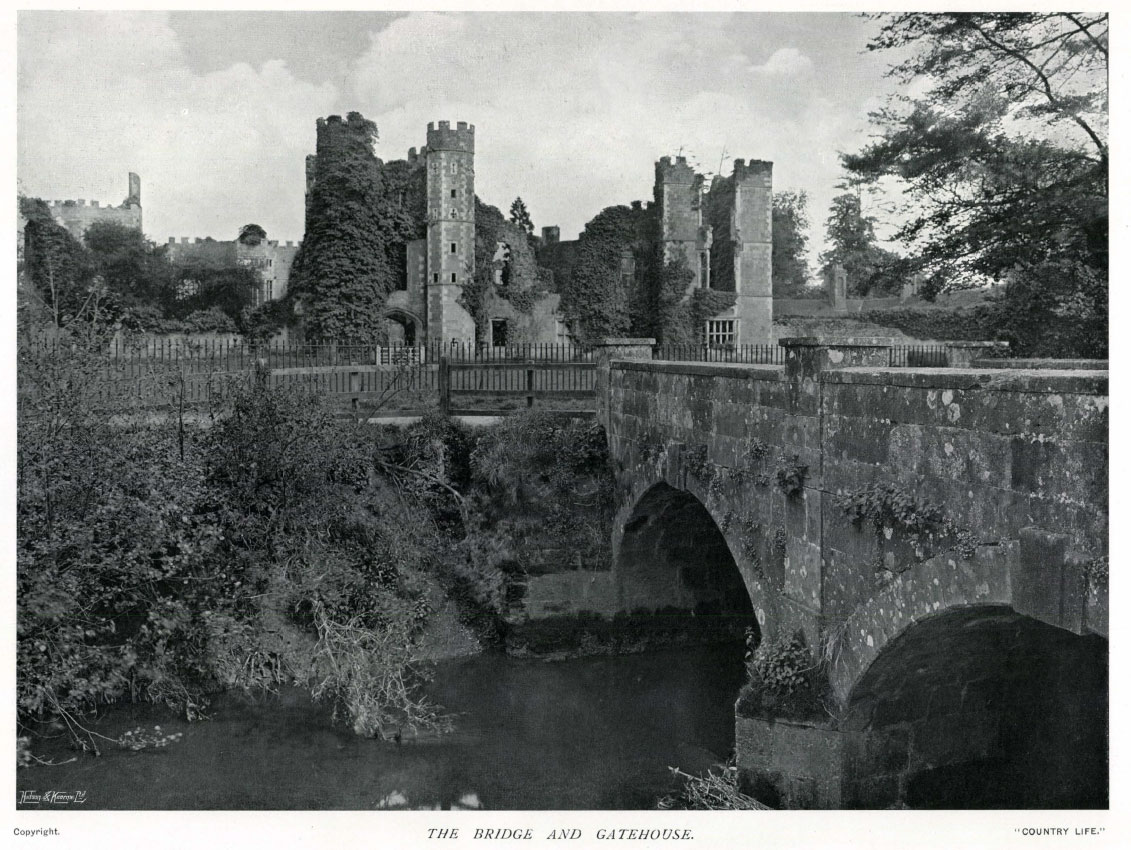

The ruins sit beside a river on the edge of Midhurst, a West Sussex town a few miles north of Chichester and east of Petersfield, and the building is as grand a castle as any in the area. In January 1910, H. Avray Tipping wrote about the place in Country Life, marvelling at the history of a castle whose history stretches back to medieval times.

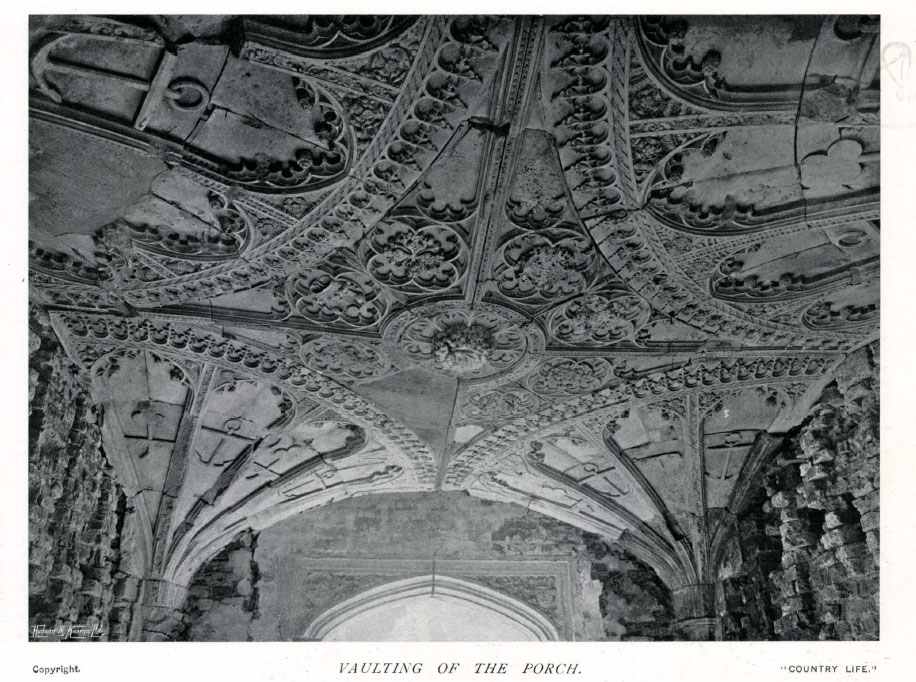

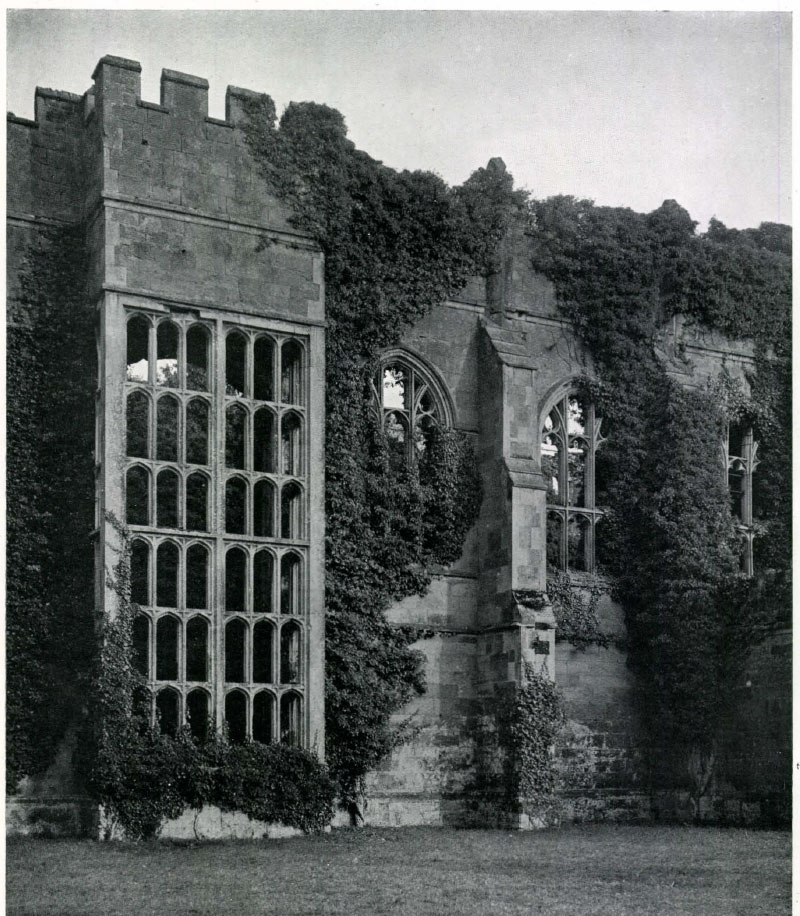

Professor Freeman described Cowdray House as having "belonged to that happy moment of our national art when purely domestic architecture was at its height," but much of its interest, even in its neglect and ruin, lies in its belonging, not to one moment, but to two at least.

The remains of the hall show the dominion of the native Gothic style barely challenged by the new Italian ideas, while the character of the other building, which, in association with it, completed the great quadrangle, betrays the triumph of the Renaissance in the form it took in the time of Elizabeth. Nor is this classification comprehensive, for the hexagonal towers, which stand at the north and south ends of the main building, appear to be the work of an earlier builder.

Tipping goes on to recount the history of the house from its glory days in the late 16th century — including a visit from Elizabeth I herself — to the late 18th century when the then-Viscount died in tragic circumstances and the castle burned down.

The eighteenth century owners of Cowdray had sufficient means to support their degree, but no g reat surplus to spend on the classicalising of the house, and Cowdray was one of the fine houses of earlier time that got through the Palladian period almost unscathed — although the great or Buck hall was divided by a floor into two storeys, and some late Italian ornamentation introduced into it and into the chapel.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It was gaining in reputation as a survival, esteemed by Horace Walpole and his school, when suddenly ruin, overwhelmed it and the male line of its ancient owners ended. The double disaster, the burning of the house and the drowning of the eighth Viscount in September, 1793, is one of the best-known tales of the vicissitudes of great families...

The estate went to the eighth Viscount's sister, who married Mr. Pointz, and the grievous but not wholly irreparable mischief caused by the fire ended in the utter annihilation of the house as a place of habitation, owing to the extreme neglect and callousness of the new owners. The fire broke out in the north gallery and spread both ways, involving the main east budding in ruin and reaching westward as far as the gate-tower. The portion of the west front south of that and the whole south building appear, from a sketch taken two months later, to have escaped. So also did the south hexagon tower, containing the kitchen below and a room used as a library above.

After the fire, worse was to come as much of what was left was taken — almost incredibly, with the knowledge and consent of the owners at the time.

The whole place lay derelict. Ivy and weather were allowed to do their worst. Anyone could come and take what he pleased. The kitchen contained "confused heaps of furniture"; the library floor was strewn with "heedless heaps" of manuscripts, "many of the papers having been carried away by persons who chanced to visit the ruins," while others were "wantonly destroyed and used as wrappers or for kindling fires."

The beautiful Italian fountain that had stood in tile middle of the court lay scattered about in bits. A neighbour admiring the fragments was told by Mr. Pointz that he could cart them away and put them together it he pleased. That is how this work of art found its way to Woolbeding, where it may still be seen.

The fountain in question — a 16th-century masterpiece by Benedetto da Rovezzano — is no longer at Woolbeding; the National Trust loaned it permanently to the V&A in 1971.

From 1843, a new attitude saw much of what was left preserved as the ruins passed into new ownership.

This attitude towards the house and records of their distinguished ancestors continued till the Pointzes were no more and a stranger bought the place. After the purchase of Cowdray by the sixth Earl of Egmont in 1843 a little more care was taken, and the ruined house has not been allowed to fall entirely to the ground. Even in its present condition it brings vividly to mind the fine style of architecture of which our sixteenth century ancestors were past-masters.

Today, Tipping's view of the ruins still holds sway: this charming and romantic site has been preserved. A 10-year effort to make the ruins safe as a visitor attraction was completed in 2006, and the adjacent walled gardens are now as pretty an event venue as you'll find in Sussex.

The joy of earning to play polo, the intoxicating sport where you'll ride 'on one of the Ferraris of the horse world'

Watching a polo match will give anyone who loves riding an urge to try it for themselves — Octavia Pollock

Credit: Ben Wright

An absolute beginner's guide to clay pigeon shooting: 'Coffee drunk and dogs cuddled, it was time to begin'

Octavia Pollock had never so much as held a gun before she decided to try clay pigeon shooting — she headed

How to make a living off your garden: 'The garden draws you in with its wonderful sense of stillness'

Making your living off your garden is a dream for many of us — but it needn't be a dream, as

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver