The tale of the couple who gave Chequers to the nation and caught the mood of war-ravaged Britain

In 1917, the newly restored Chequers was gifted to the nation as the country seat of Britain’s Prime Ministers. John Goodall turns to a personal diary to explain how this came about; photographs by Paul Highnam.

On September 22, 1912, the leaseholders of Chequers Court, Arthur and Ruth Lee, read in the Sunday papers that the owner of the house, Delaval Astley, had been killed in a flying accident. As was described last week, the Lees had just restored the property at enormous expense and the news came as a shock. The accident would prove a turning point in the history of Chequers and directly encouraged the Lees to make a gift of the house to the nation as the country seat of Britain’s Prime Ministers. To understand why, it is necessary to return to Ruth’s compelling diaries.

All Astley’s property, including the freehold of Chequers, passed to his wife, ‘May Kinder, a chorus girl from Philadelphia’, as Ruth later noted. An American herself, it is nevertheless implicit from the diaries that she believed the Astley family to be embarrassed by the connection. The Lees received news of the tragedy, moreover, after troubles of their own.

Arthur, then serving as an MP, and Ruth had recently both been seriously ill and the latter had undergone a major operation. Illness changed their attitude towards a house they had leased for two lifetimes only three years before and restored, especially as they remained childless.

On October 6, Ruth tried to articulate — in rather tortured sentences — her concerns:

‘The family may want to buy Chequers from the widow [May Astley] and might ask us to do go between and pretend we wanted to buy it for ourselves. This suggested the train of thought that it would be greatly to our interest to own it ourselves. Otherwise we should be making the Astleys a present of all our chance of ever realising on the [blank] pounds we have spent and in event of our losing our fortune or my dying that wd be a most serious thing. Tho of course we at one time thought the loss inevitable. Later it became more and more plain to us how much we shd like to buy it if possible and leave it in our wills as an official country residence for the Prime Minister — a thing we had often tho’t of vaguely.’

The following day, Ruth wondered whether ‘anything will come of the plan in connection with Chequers which we talked of yesterday for the first time as a serious possibility’. Thus, the idea of Chequers as a country seat for the Prime Minister was in currency before 1912, but the plane crash indirectly gave it reality. On October 19, when sitting in the sun on the appropriately named Statesman’s Walk, they introduced ‘our “epoch making idea” — the developed scheme about Prime Ministers!’ to Ruth’s sister, Faith.

The couple also sounded out the Astley family. On December 5, Mrs Reginald Astley was entertained by the Lees at the House of Commons and ‘she seems quite pleased with our scheme in Chequers’. Fundamental to this, however, was the purchase of the house and, although a proposal was formulated for the sale in 1913, no direct answer was initially forthcoming.

Throughout this period, the Lees continued to collect furniture and pictures for the house. They also began planning a complete series of stained-glass windows in the Long Gallery on October 31, 1911. Externally, the Lees initiated a two-year redevelopment of the garden. It was completed in 1913 and again involved Country Life.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

On September 10, 1910, when visiting their neighbours, the Aubrey Fletchers, at Dorton House, Buckinghamshire, the Lees had been shown ‘beautiful’ plans for a new garden by the magazine’s Architectural Editor H. Avray Tipping. From this, Ruth reported, ‘we got the idea to get his suggestions for Chequers’.

Tipping’s first full visit to Chequers followed on October 27, 1910. He:

‘arr. About 3 and almost immediately started with Smith [the gardener] to lay out the new orchard… Mr Tipping in to tea and after talking garden I took him round the house, showed him the pictures etc. connected with the history of the house which he is to write up for Country Life’.

He was back again on November 24, when he walked around the garden with Ruth, warmly wrapped up.

She had strong opinions about the designs and warned him in January 1911 ‘to keep the details of the garden architecture as much Jacobean as possible and away from William III’. Again, Tipping must have used the opportunity to check some details for his article and the proofs arrived two days later. It appeared, as was described last week, on December 31.

Work to the formal garden itself to the south of the house actually got under way early in November 1912 and it proved painful to Ruth. From the first, she was horrified by the colour of the bricks used for the enclosing walls and pavillions.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Arthur initially travelled to France as a staff colonel, but he became disillusioned with Britain’s political leadership and, in October 1915, he was invited back by his former political opponent, Lloyd George. When Lloyd George moved to the War Office in October 1915, he appointed Lee his private secretary. The frenetic activity of the couple’s wartime life is well reflected in the diary entries, which begin to break their allotted pages and are often heavily corrected.

Chequers was briefly converted into a hospital. Lee was made a KCB in July 1915 and expected further favours when Lloyd George became Prime Minister late in 1916. Much to his disappointment, however, he was passed over for a post until February 1917, when he was appointed director-general of Food Production.

In August, however, he wrote to the Prime Minister offering the house to the nation. On August 30, Ruth noted with relief:

‘A. tel. yesterday that L[loyd] G[eorge] has at last answered about Chequers and such a satisfactory letter — he read it to me over the telephone… NOW we can go ahead with the scheme.’

The Prime Minister’s interest in the project was to be crucial to its long-term success.

The drafted terms of the gift, later formalised within the Chequers Estate Act of 1917, placed the house, collections and estate in trust for the use of future Prime Ministers with an endowment of £100,000. It also reserved the use of the house to the Lees until their deaths. The public announcement of the scheme was very carefully managed.

On September 3, Ruth and Arthur were ‘very busy getting copies of our Chequers scheme ready to send out to the trustees. We are going to put some of the old Country Life pictures with each type-written copy… I spent a good deal of time today cutting the pictures out [of] old numbers’. Tipping was also preparing another set of three articles for Country Life to accompany the announcement and visited Chequers to confirm their details on September 30. A formal press release was sent out on October 4.

The gift precisely caught the patriotic feeling of war-weary England. The following day, Ruth delightedly wrote:

‘The papers are simply covered with it! I had not known at all — nor had Arthur — how much interest the public would take in it.’

The first of the Country Life articles came out on October 6 and the Lees’ village friend, one Mrs Files, found her copy ‘in great demand! She says they [the village] all say it is so clever of Sir Arthur to have thought it out so wonderfully and they say it will always keep “trade” in the neighbourhood’.

‘A wonderful christening for Chequers in its new role’ followed that very weekend, when a conference over the Allied command, including Lloyd George, Marshal Foch, Gen Smuts, the French Prime Minister, Paul Painlevé and Arthur Balfour, was held. October 13 was: ‘A very hectic day… we’ve not had a party since before the war and the house has never been entirely put back in order since the hospital.’

Ruth left the house with relief for the conference itself:

‘As I drove out there was a policeman at each gate arranged by A. of course. He saw the head of the Aylesbury police… [and] said he hoped they liked it in Aylesbury. And he said “why they can’t talk of anything else sir”.’

The Prime Minister occupied Lee’s bedroom and the discussions took place ‘at Lloyd George’s insistence’ in his small study. Most of the guests greatly enjoyed themselves, but Painlevé was in the final crisis of his administration and turned up to dinner ‘in an awful state and said he must return at once, wanted to go by airoplane [sic]. Finally, after much telephoning, they fixed him up with the admiralty for a destroyer’. Lloyd George, by contrast, ‘remained in good spirits and very pleased with Chequers. He planted an oak in the east park and before he left took another long walk up Beacon Hill’.

The conference was a one-off occasion, but the Lees — and, by their report, Lloyd George — were convinced of the positive contribution made by the house and its setting to the discussion. Lee remained busily engaged in government with the crucial job of increasing agricultural production. One of his legacies was the National Institute of Agricultural Botany, also a body with a connection with this magazine (Country Life, January 14, 2015). On leaving office in 1918, he was created Baron Lee of Fareham. Then, in 1920, there was talk of Lee being appointed Viceroy of India. By this time, however, the Lees were worried about their scheme for Chequers.

In September, Ruth complained people had ‘overlooked the “after our death” part of the announcement’ and expressed a concern that Lloyd George really wanted a smaller country house. The uncertainty catalysed a bold and sudden decision. On September 22, she wrote: ‘We have now decided definitely to give it up permanently — endowment and all and hand it over to the state whether we go to India or not — provided of course LG will agree to live there. A. wd like to have it all settled by Armistice Day.’

A letter was sent to Lloyd George, formally offering him the house, on October 2, and the Lees waited on the edge of their seats for a reply. He delightedly accepted, jocularly demanding to know why Ruth was in ‘his house’ rather than available in London for a celebratory dinner. Less than two weeks later, an eminent body of trustees was assembled and the trust came into being.

Then came the process of cataloguing the contents, a task undertaken by the South Kensington Museum and National Gallery. Every stage of the work was accompanied by irritations and difficulties and, as November progressed, the Lees felt that Lloyd George had unaccountably turned against them.

On October 15, Ruth reminded herself that the importance of the gift lay beyond such ‘arrogances’ and that ‘the affairs of the country really will go better if the Prime Minister has a place of Peace and rest and beauty in bracing healthful air to go to at weekends where he can be refreshed and reinvigorated’.

On November 13, Sir Charles Holmes, director of the National Gallery, came with an assistant, ‘a most irritating personality’, determined to reattribute every picture in the house. So, too, did long-standing friend and Society portraitist, Philip de László, who swiftly began a portrait of the Lees intended as their final bequest to the house.

To complicate matters even further, the director turned out to have played a role in de László's wartime internment and the artist was ‘distressed’ to encounter him. Nevertheless, the picture was completed three days later and hangs today in the entrance lobby of the house.

There remained only one final task. On December 12, the Lees went to inspect their graves, which were being dug by a groundsman: ‘We are pretending to others that it is for a wireless mast… we are going to have our coffins just touch.’

The Lees’ wedding anniversary passed on December 23 and Ruth’s 47th birthday four days later, 10 years to the day that they had first celebrated it in the house. They stayed at Chequers until January 8 for a farewell dinner attended by the Prime Minister, to whom the Lees were once again reconciled.

Ruth recorded Lloyd George’s speech: ‘He made us feel that he had need of Chequers and that his successors were likely to have ever increasing need of it and what it represented… [and that Chequers] would in his opinion bear great fruit and have a deep and subtle and far-reaching effect on the destinies of the country.’ Present circumstances make it hard to disagree.

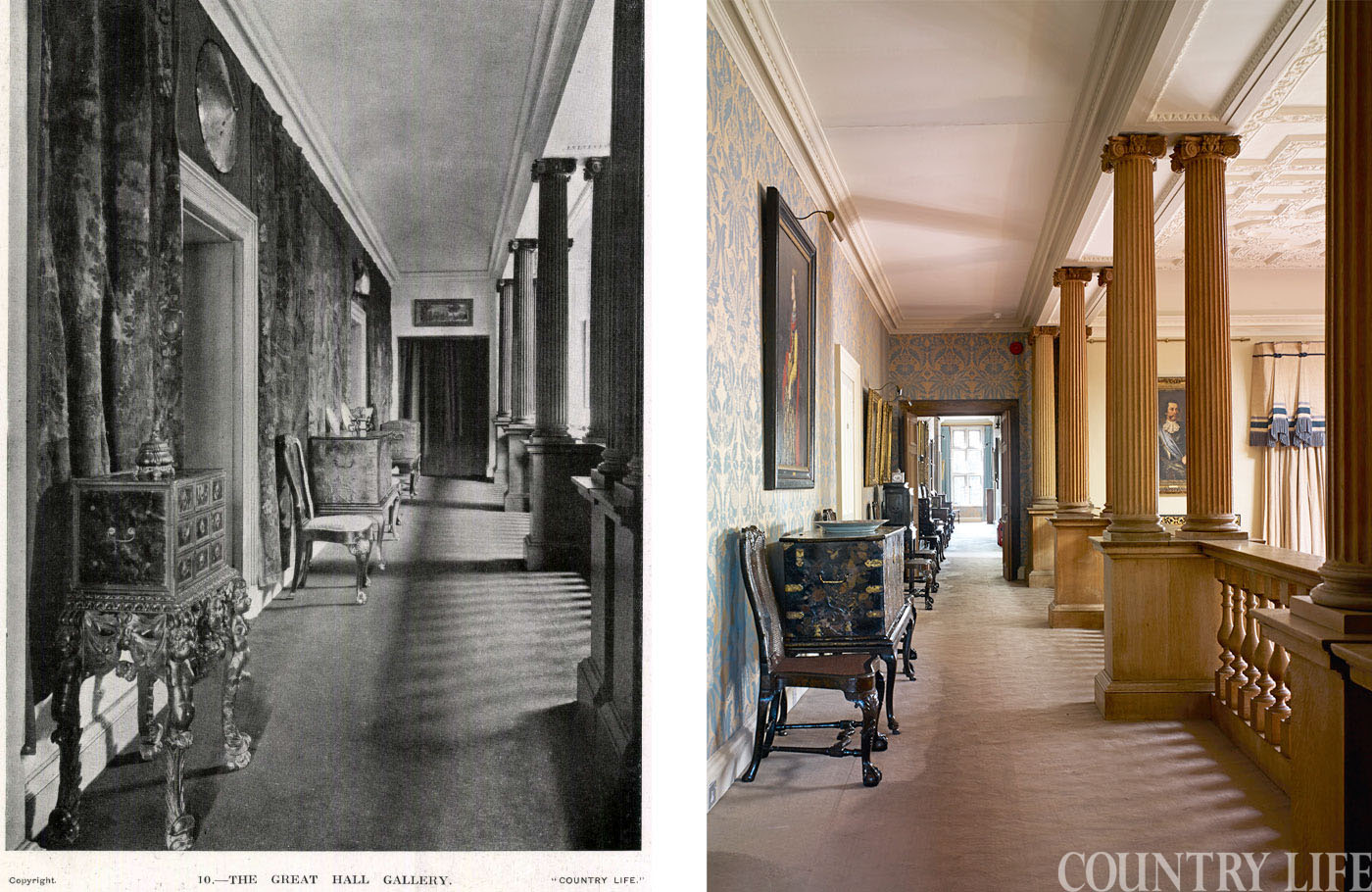

How Chequers has changed — and stayed the same — in a century, as pictured in Country Life

We take a look at Chequers is now, and as it was 103 years ago, when Country Life visited following

Credit: Alamy

11 things you never knew about the jackdaw, the bird that just loves people

Ian Morton takes a look at the jackdaw, a bird with a real affinity for man – despite a chequered reputation

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Rodel House: The Georgian marvel in the heart of the Outer Hebrides

Rodel House: The Georgian marvel in the heart of the Outer HebridesAn improving landlord in the Outer Hebrides created a remote Georgian house that has just undergone a stylish, but unpretentious remodelling, as Mary Miers reports. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

By Mary Miers

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle