The tale of Ireland's 'House Burning Mania' of 1919-1923

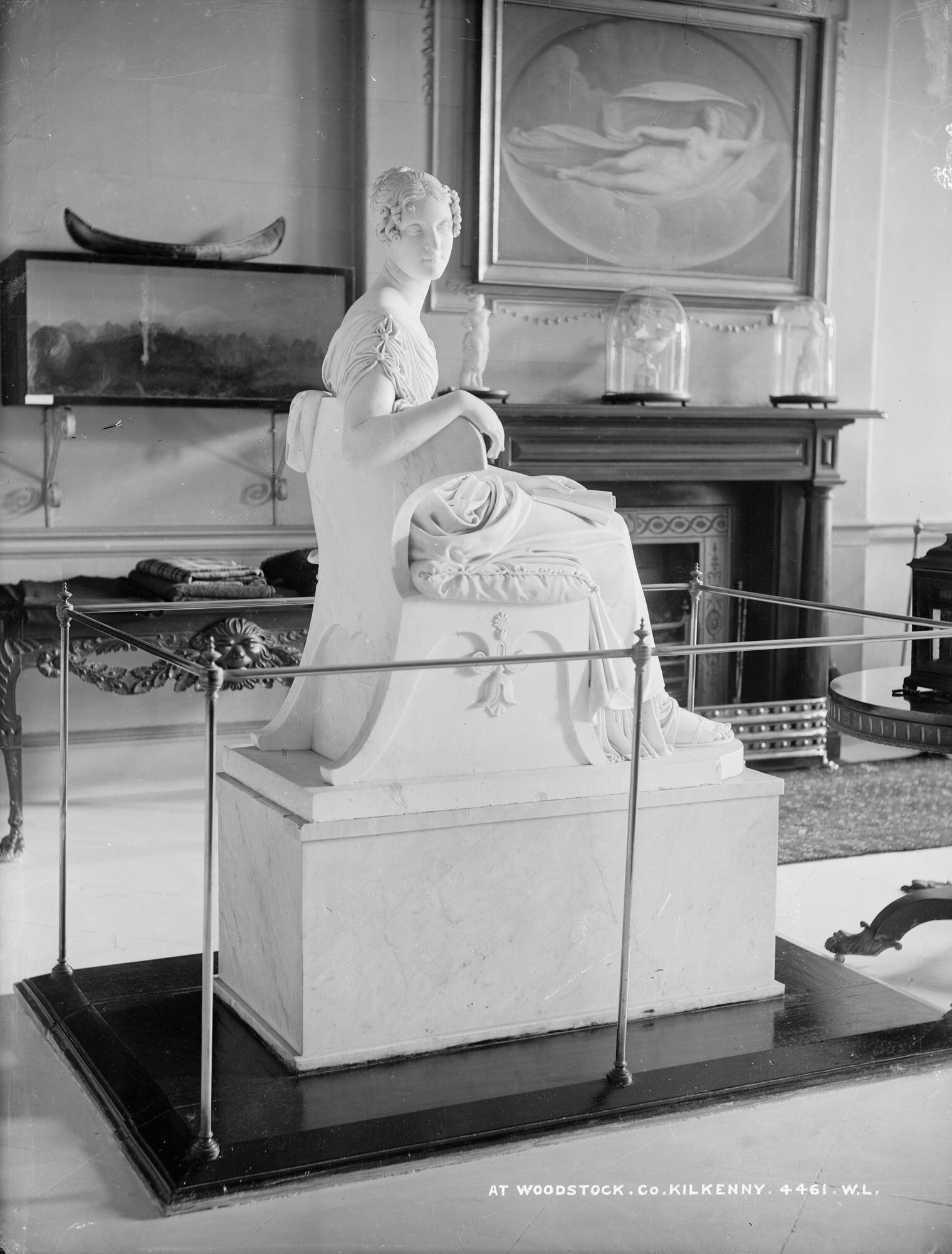

Between 1919 and 1923, in the War of Independence and the subsequent civil war, nearly 300 country houses were burned in Ireland. To mark the centenary of the events, Terence Dooley re-appraises the motives behind this destruction.

Late on the night of February 4, 1921, a local company of the Irish Republican Army came to Summerhill House, Co Meath, home of the 5th Baron Langford, and knocked very loudly on the back door. The men came on the orders of the Irish revolutionary and politician Michael Collins to burn the house. Local IRA leader Seán Boylan later claimed that Collins had been told that Summerhill — a magnificent Palladian pile referred to as ‘the Irish Versailles’, believed to have been designed by Sir Edward Lovett Pearce and built for Hercules Langford Rowley in the early 1730s — was to be used as a barracks by Crown forces. As the house was strategically located ‘on high ground which commanded one of the routes to the west’, its destruction was imperative to the IRA’s freedom of movement.

The butler and a handful of servants who were present took the decision not to open the door. It was futile; the raiders simply broke in and forced the servants to flee to the woods. They sprinkled drums of petrol over the floors and doused furniture they had piled into the middle of rooms, before turning the house into a conflagration that lit up the night sky. The house was ‘reduced to a mass of blackened ruins’ with the almost complete loss of its contents.

The Irish War of Independence was in its second year. On January 21, 1919 an Irish parliament, Dáil Éireann, had met in Dublin and proclaimed Irish independence from Britain. In the spring of 1920, the Dáil’s military wing, the IRA, launched its campaign against the Royal Irish Constabulary and burned hundreds of police barracks.

When the police reinforcements — Auxiliaries and Black and Tans — arrived later that year, they used ‘Big Houses’ as billets, so numerous places, such as Summerhill, became IRA targets. Of course, there were other reasons for these arson attacks and the destruction of every house has its own particular history. Some generalisations, however, can be made.

Until recently, the burning of Irish country houses during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21) and Civil War (1922–23) has attracted little attention, yet, in the area of the present Irish Republic, nearly 300 Big Houses were destroyed. During both conflicts, these burnings were most heavily concentrated in the main theatres of war, especially the counties of Cork and Tipperary.

By contrast, there were fewer than a dozen destroyed in the area of Northern Ireland (which was established under the Government of Ireland Act of 1920), essentially because of the significant differences in the political, demographic and social conditions there.

Linked to the politics of burning during the War of Independence was the fact that country-house owners were regarded as enemies of the emerging revolutionary state. The perception of the Big House as the physical symbol of conquest, plantation and colonial oppression remained current. As the historian Vincent Comerford has written of the earlier Land War period (1879–81): ‘Landlord and big house would do as synecdoche for all the historical grievances of the nationalist narrative.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country-house owners, therefore, became caught up in the spiralling violence of reprisal and counter-reprisal that characterised the conflict between the IRA and Crown forces. For example, in June 1921, after Col Thomas Lambert, the commanding officer of the 13th Brigade 1st Division, was killed in an ambush near Athlone, the Black and Tans burned six farmhouses with suspected Sinn Féin and IRA connections in the nights that followed. Then, at 3.30am on the morning of July 3, the local IRA exacted its own revenge by burning Moydrum Castle, the home of Lord Castlemaine. His wife was told: ‘We will give you five minutes to clear out. We are burning your house as a reprisal of the recent burnings at Coosan and Mount Temple.’

The heaviest period of burning was in the six weeks leading up to the announcement of the Anglo-Irish truce on July 11, 1921: 33 houses or 40% of the War of Independence total were destroyed, leading The Irish Times to headline the ‘House Burning Mania’ that was sweeping the country.

The conflict had intensified and become more brutal; Cork IRA leader Tom Barry later recalled: ‘Castles, mansions and residences were sent up in flames by the IRA immediately after the British fire gangs had razed the homes of Irish Republicans… If the Republicans of West Cork were to be homeless and without shelter, then so too would be the British supporters.’

In some cases, historical grievances were cited as justification for destruction. When Kilbolane Castle was burned in Co Cork in June 1920, for example, the Limerick Echo reminded its readers that its original owner, the Earl of Clare, had played a major role in the passing of the Act of Union in 1800 ‘by bribery, corruption and fraud’. When Lorcan Park House was burned in Co Tipperary a year later, the local newspaper recalled the eviction of 200 families from the estate after the Famine of 1845–51.

By contrast, a house such as Castle Cooke, the Cork residence of Col William Cooke-Collis, might have been burned because he had a long and distinguished military career in the British army, which meant his loyalism was seen as a threat to local republicans. However, it may equally as likely have been motivated by his continued ownership of large estates, which brought him into conflict with land-hungry young men from landless or small-farm backgrounds (who may also have been IRA members.)

The agrarian dimension of the revolutionary period in Ireland should not be underestimated. Irish land reform between 1870 and 1909 did widen property ownership. Nevertheless, a very high percentage of Irish farms all over the country were too small to be viable. Col George O’Callaghan Westropp from Clare had written Notes on the Defence of Irish Country Houses at the beginning of the third Home Rule crisis in 1912, in which he warned his fellow landowners that they should prepare to deal with raids by gangs of land-hungry nationalists. This very much became the case, especially during the Civil War. The burning of Tubberdaly in Co Offaly was carried out by men who were both IRA members and former employees of the estate who had taken forcible possession of parts of the demesne after they had been made redundant following a labourers’ strike in 1919. They used the political conflict of the time to secure their farm holdings.

After Gola was burned in Monaghan, the local Sinn Féin club took steps to ensure that the demesne would ‘be divided into small farms and sold at a [reasonable] price so that men in the neighbourhood or men who had sons in jail could have a chance’.

The hunger for land became more intense in the Civil War, which goes some way to explaining why there were 2½ times more houses burned in 1922–23 (a total of 199) than during the War of Independence. The obvious facilitator of this destruction was the absence of all forces of law and order from the countryside following the withdrawal of the Crown forces and the disbandment of the RIC by the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty signed in December 1921.

The county inspector of Tipperary saw the danger coming a month after the truce: ‘The hunger for land is great, those who are landowners want more, while those who have none and who have been gunmen believe that the estates of Loyalists such as Kilboy once cleared will be divided up amongst them.’ Indeed, Kilboy was burnt on August 4, 1922; Lord Dunalley’s steward wrote to him: ‘Such wanton destruction was never witnessed.’

There were, of course, other reasons for the massive escalation in burnings. Vacated houses such as the neo-Gothic extravaganza that was Mitchelstown Castle in Co Cork were billeted by republican forces and then destroyed upon evacuation. Their occupiers had little respect for the contents: at Mitchelstown, officers used the back of oil-painted canvases to draw maps and books from the library were used as substitutes for sandbags in the windows.

Those hostile to accommodation with the British government and the Anglo-Irish Treaty signed in December 1921 (which split the independence movement and catalysed the Civil War) also targeted the homes of senators drawn from Anglo-Irish families and recently appointed to the Free State Senate: Sir John Keane’s Cappoquin in Co Waterford (in this case, agrarian motives were also lurking in the background); Moore Hall in Co Mayo (Col Maurice Moore’s family residence); and Sir Thomas Esmonde’s Ballynastragh in Co Wexford, destroyed with all ‘its beautiful and precious things’, which Esmonde blamed on the ‘ignorant dupes’ of de Valera.

The burnings of senators’ houses was mixed in with reprisals for executions under the Public Safety Act introduced by the Provisional Government in November 1922. For example, when the raiders came to burn the Earl of Mayo’s home, Palmerstown House, Co Kildare, on January 29, 1923, they told him it was in reprisal for the execution of six opponents of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in the Curragh earlier that month.

In the vast majority of cases, destruction was usually complete. Castleshane in Monaghan became ‘a glowing mass of all material of all kinds’, where beautifully crafted silverware became fused with crude metal objects. Family portraits were destroyed, the only physical reminders of generations of ancestors; archives were destroyed, wiping out the histories of a whole local community; and the gramophone and records ‘had pipped it’, symbolising the destruction of the material culture of the next generation.

The daughter of the house, whose life had already been marred by the Great War, was disconsolate; Gill Lucas Scudamore wrote: ‘Whenever we try to be happy, something seems to spoil it all… I don’t feel as if I ever want to do anything ever anymore.’

Destruction was often accompanied by looting. Lord Dunalley ‘heard on excellent authority’ that the contents of Kilboy were ‘in many of the houses round about’. In October 1924, his solicitor advised him not to undertake the task of identifying them personally: ‘It would be putting you in a most invidious position and would, I think, cause great ill feeling, which has now happily died down.’

In the direct aftermath, the ruins of big houses such as Castleshane became a playground for a class that, in the past, would not have been allowed inside their estate walls. The Irish landscape was transformed as demesnes were compulsorily acquired by the state under the 1923 Land Act and split into small farms. The compensation process was complex, long drawn out and usually unsatisfactory, as far as owners were concerned.

In September 1921, Baron Langford, the owner of Summerhill, made a claim for £100,000 for the house and £30,000 for the contents. He was awarded £65,000 and £11,000, but this was later reduced on appeal by the Free State government to a total of £43,500. Little wonder that his cousin advised him: ‘Much as I should like to see the old house rebuilt, one must remember that if even this was done you could not put back the old things that formed part of it.’ The ruins were finally demolished in the 1950s.

Only a tiny proportion of the houses burned were ever rebuilt, such as Kilboy (featured in Country Life, September 7, 2016) and Cappoquin. We will never know the full extent of the collateral loss of collections burned or looted. Ruins such as Summerhill stood like ghostly figures for generations to come, seen by most nationalists in post-independent Ireland as symbols of a victory over the former coloniser. For generations, it was difficult to see beyond this to contemplate what Ireland also lost in this destruction.

Professor Terence Dooley is the Director of the Centre for the Study of Historic Irish Houses and Estates at Maynooth University.

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwards

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwardsCampaigners in England often point to Scotland as an example of how brilliantly Right to Roam works, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, says Patrick Galbraith.

By Patrick Galbraith