The real-life places that inspired Jane Austen's most memorable fictional country houses

Country houses serve as an ever-charming backdrop to the novels of Jane Austen. With the help of specially commissioned drawings, Jeremy Musson considers her treatment of their architecture. Illustrations by Matthew Rice.

We become aware of country houses in the novels of Jane Austen in different ways. Her descriptions are sparse; there are no Trollopian musings on the colour of old stone or strangely elaborated Dickensian interiors, but the houses spring into the reader’s imagination. They are the vital surroundings around and within which the action takes place and, at the same time, symbols of longing and loss, of status, settled responsibility and order.

Although seeking a single model for a fictional creation is a risky enterprise, familiar surroundings do provide points of reference and the domestic settings of Austen’s own life point to possible sources of inspiration. They include the handsome rectory at Steventon, Hampshire, where she grew up in a lively, clerical family with a well-connected mother. On her father’s retirement, the rectory passed to her clergyman brother James and, after some unsettled years, Chawton Cottage, in the Hampshire village of Chawton, became Austen’s home (with her mother and sister Cassandra), from 1809 until she died in 1817.

The cottage was part of the estate of Chawton House, inherited by her younger brother Edward from distant cousin Thomas Knight — the main house, a memorable gabled, late-16th-century building, extended in the mid 17th century. Other local country seats, such as The Vyne, Hackwood Park, Hurstbourne Park and Kempshott Park would have been known through social interactions. Their owners were mostly titled ‘nobility’, but only the gentry Chutes at The Vyne could claim to be a historic county family.

Other Hampshire gentry houses include Manydown Park, of which Austen nearly became chatelaine in 1802, and Ashe Park, where she dined with the Holder brothers. Of the latter, she noted afterwards that ‘to sit in idleness over a good fire in a well-proportioned room is a luxurious sensation’. Her brother Edward also inherited fine, 18th-century Godmersham Park in Kent and, perhaps because his wife Elizabeth Bridges was from a well-connected Kent family, he made this estate his principal seat. A wealthy Austen uncle, who lived in a 1680s house — The Red House — in Sevenoaks, Kent, was lawyer to the Sackvilles at Knole.

One of Austen’s mother’s grander cousins, Thomas Leigh, inherited Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire, creating a possible connection between the Classical form of its chapel and that of Sotherton Court, which so disappoints Fanny Price in Mansfield Park (1814). Hoping for medieval romance, Fanny finds only ‘a mere spacious, oblong room, fitted up for the purpose of devotion: with nothing more striking or more solemn than the profusion of mahogany, and the crimson velvet cushions’. The heroine tells her cousin Edmund Bertram regretfully that it is ‘not my idea of a chapel. There is nothing awful here, nothing melancholy, nothing grand. Here are no aisles, no arches, no inscriptions, no banners’.

At the time Austen was writing, knowledge of architecture was expected in gentry and well-educated circles. Her references to improvements to smaller residences — often a rectory or cottage made available to a widow — remind us of the practical necessity of adapting as circumstances change. The two real-life architects who are mentioned in her novels are Joseph Bonomi — in Sense and Sensibility (first drafted in the 1790s, but revised and published in 1811) — and Humphry Repton (principally a land- scape architect), in Mansfield Park, and both worked on projects within her wider family. Her depictions, right down to Repton’s exorbitant fees of five guineas a day, may partly serve as a family joke.

The actual architecture of Pemberley gets only a glancing reference in Pride and Prejudice (also first drafted in the 1790s, but revised from 1811 and published in 1813), but we know the effect of the first sight of this ‘large, handsome stone building, standing well on rising ground’. The other major pile encountered in the same novel is, of course, Rosings Park (seat of the proud Lady Catherine de Bourgh, aunt of Pemberley’s owner Mr Darcy), ‘a handsome modern building, well situated on rising ground’. As the architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner himself observed in 1968, these could easily have been descriptions of the same house.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

However, for Rosings we also have Elizabeth Bennet’s reactions to the descriptions of the unctuous Mr Collins, from which we discover she is ‘but slightly affected by his enumeration of the windows in front of the house, and his relation of what the glazing altogether had originally cost Sir Lewis de Bourgh’. Elsewhere, the clergyman describes a chimneypiece costing £800.

Visiting Pemberley as a gentry-tourist, Elizabeth finds a house ‘backed by a ridge of high woody hills; and in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal nor falsely adorned’. Writing in Jane Austen and the English Landscape (1996), landscape historian Mavis Batey makes a good case for the setting resembling that of Ilam Hall in Derbyshire. During her tour of Pemberley, Elizabeth is constantly drawn to the view. The dining parlour ‘was a large, well-proportioned room, handsomely fitted up. Elizabeth, after slightly surveying it, went to a window to enjoy its prospect. The hill, crowned with wood, which they had descended, receiving increased abruptness from the distance, was a beautiful object. Every disposition of the ground was good’. Although impressive, there is a sense of direct connection to the landscape, a quality referenced in famous lines from Emma (1815): ‘It was a sweet view — sweet to the eye and the mind. English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a sun bright, without being oppressive.’

The interiors of Pemberley are impressionistic: rooms ‘lofty and handsome, and their furniture suitable to the fortune of its proprietor’, a picture gallery and ‘very pretty sitting room’, as well as bedrooms grand enough to be included in a guided tour. But it is the well-managed beauty of the landscape that com- mands the heroine’s heart. It is all enough to make her wonder, as the housekeeper shows her round: ‘What praise is more valuable than the praise of an intelligent servant?’

In Pride and Prejudice, we find Netherfield Park, Hertfordshire, too, the property rented by Mr Bingley, and Longbourn, the home of the Bennets. Netherfield is capable of accommodating a house party of six, leaving bedrooms to spare, and its capacious drawing room (Fig 1) is used simultaneously for cards, music, reading, writing letters and also as a theatre of social accomplishments. Here, Miss Bingley can invite her guest to ‘take a turn about the room… very refreshing after sitting so long in one attitude’ and separate parties can converse with an element of privacy.

Sotherton Court, Northamptonshire, the Rushworth family seat in Mansfield Park, is an old gentry house built ‘in Elizabeth’s time’. It has ‘many good rooms’ and is ‘a large, regular, brick building; heavy, but respectable looking’. This carries an echo of The Vyne, a stately, brick-built house, or even the gabled, picturesque Chawton House, in flint and brick, perhaps even a hint of Knole. The young Mr Rushworth considers his inheritance ‘a dismal old prison’ and wants to improve the landscape (perhaps with Repton, suggests his fiancée).

As his widowed mother shows visitors around, they find an abundance of pictures, of which ‘the larger part were family portraits, no longer anything to anybody but Mrs Rushworth, who had been at great pains to learn all that the housekeeper could teach, and was now almost equally well qualified to shew the house’. We are reminded of the role of upper servants in transmitting historical information and the frequency of such house tours; the sophisticated Miss Crawford ‘had seen scores of great houses, and cared for none of them’.

The titular building of Northanger Abbey (written in the late 1790s, but not published until 1817), which is said to lie some 30 miles from Bath, is a grave disappointment to Catherine Morland; her ideas were shaped by Gothic novels (which Austen parodies in this book) and she longs for something ancient and moody. They approach along a drive and she hopes to catch ‘a glimpse of its massy walls of grey stone, rising amidst a grove of ancient oaks, with the last beams of the sun playing in beautiful splendour on its high Gothic windows’. Instead, she finds a low, modern-looking house; and it is equally as disappointing inside. ‘The fireplace, where she had expected the ample width and ponderous carving of former times, was contracted to a Rumford [a popular patent coal-burning grate] with slabs of plain though handsome marble, and ornaments over it of the prettiest English china’. She is told the windows were preserved ‘in their Gothic form with reverential care’ but their Gothic is not the same as hers. ‘To be sure, the pointed arch was preserved — the form of them was Gothic — they might be even casements — but every pane was so large, so clear, so light!’ Here is no indication of the ‘painted glass, dirt, and cobwebs’ of her Gothic imagination.

Miss Morland is subjected to a painfully thorough room-by-room tour by Gen Tilney, who has erroneously marked her out as a suitable heiress-bride for his son. She even views the extensive domestic offices of the house, complete with an embarrassed footman in ‘dishabille’. There is a common drawing room, a principal drawing room, a library, billiard room, dining room, and modernised kitchen within the walls of the ancient kitchen. The large and lofty hall has ‘a broad staircase of shining oak’ with ‘many flights and many landing-places’ and, at the top, ‘a long, wide gallery’.

The main house in Mansfield Park — supposedly in Northamptonshire — is the seat of Sir Thomas Bertram (Fig 4) and the origins of his wealth in the West Indies points to slavery, with Austen’s choice of house name possibly referencing Lord Mansfield, who was responsible for the first significant anti-slavery judgement in 1772. Described as a ‘spacious modern built house’, deserving ‘to be in any collection of engravings of gentlemen’s seats’, it may be part modelled on Godmersham Park, the 1730s Palladian house inherited by Edward Austen, which was later included in just such a collection of engravings, William Watts’s Seats of the Nobility and Gentry (1779–86), a book filled with exactly the kind of brief descriptions Austen uses in her novels and which includes Godmersham in the 1784 volume.

Yet perhaps the best evocation of Mansfield Park comes in its absence, when Fanny is sent home to her family’s cramped quarters in Portsmouth to consider her wilfulness in not accepting a proposal. Remembering Mansfield, she realises: ‘Everything where she now was in full contrast to it. The elegance, propriety, regularity, harmony, and perhaps, above all, the peace and tranquillity of Mansfield, were brought to her remembrance every hour of the day, by the pre- valence of everything opposite to them here.’

Donwell Abbey (Fig 5), the seat of thoughtful, unpretentious Mr Knightley in Emma, evokes quiet admiration from the heroine. Larger than Emma’s home at Hartfield, it is ‘totally unlike it, covering a good deal of ground, rambling and irregular, with many comfortable, and one or two handsome rooms. It was just what it ought to be, and it looked what it was — and Emma felt an increasing respect for it, as the residence of a family of such true gentility, untainted in blood and understanding’.

We later learn that ‘its ample gardens’ stretch ‘down to meadows washed by a stream’ and are told that the village of Highbury is in Surrey, with Emma’s sister’s house some 16 miles away. There are echoes in the description of Donwell Abbey of houses such as Chawton House and, perhaps, of The Vyne. The novel was partly written when Austen was staying at the handsome 18th-century rectory of her uncle at Great Bookham, Surrey, which may have been the model for Emma’s father’s home of Hartfield.

In Sense and Sensibility, the Dashwood daughters are obliged to leave their large house, Norland Park in Sussex, after the death of their father. They move with their mother to Barton Cottage in Devon and we learn that ‘as a cottage it was defective, for the building was regular, the roof was tiled, the window shutters were not painted green, nor were the walls covered with honeysuckles’. This is no fashionable cottage ornée, of the kind Austen is likely to have known from picturesque, white-walled Houghton Lodge in Hampshire, but this distinction is lost on the vain and foolish Mr Robert Ferrars, who tediously opines: ‘I am excessively fond of a cottage; there is always so much comfort, so much elegance about them.’ His enthusiasm leads him to consign to the fire two designs that Bonomi — known for his neo-Roman Classical boxes — has drawn up for his friend Lord Courtland.

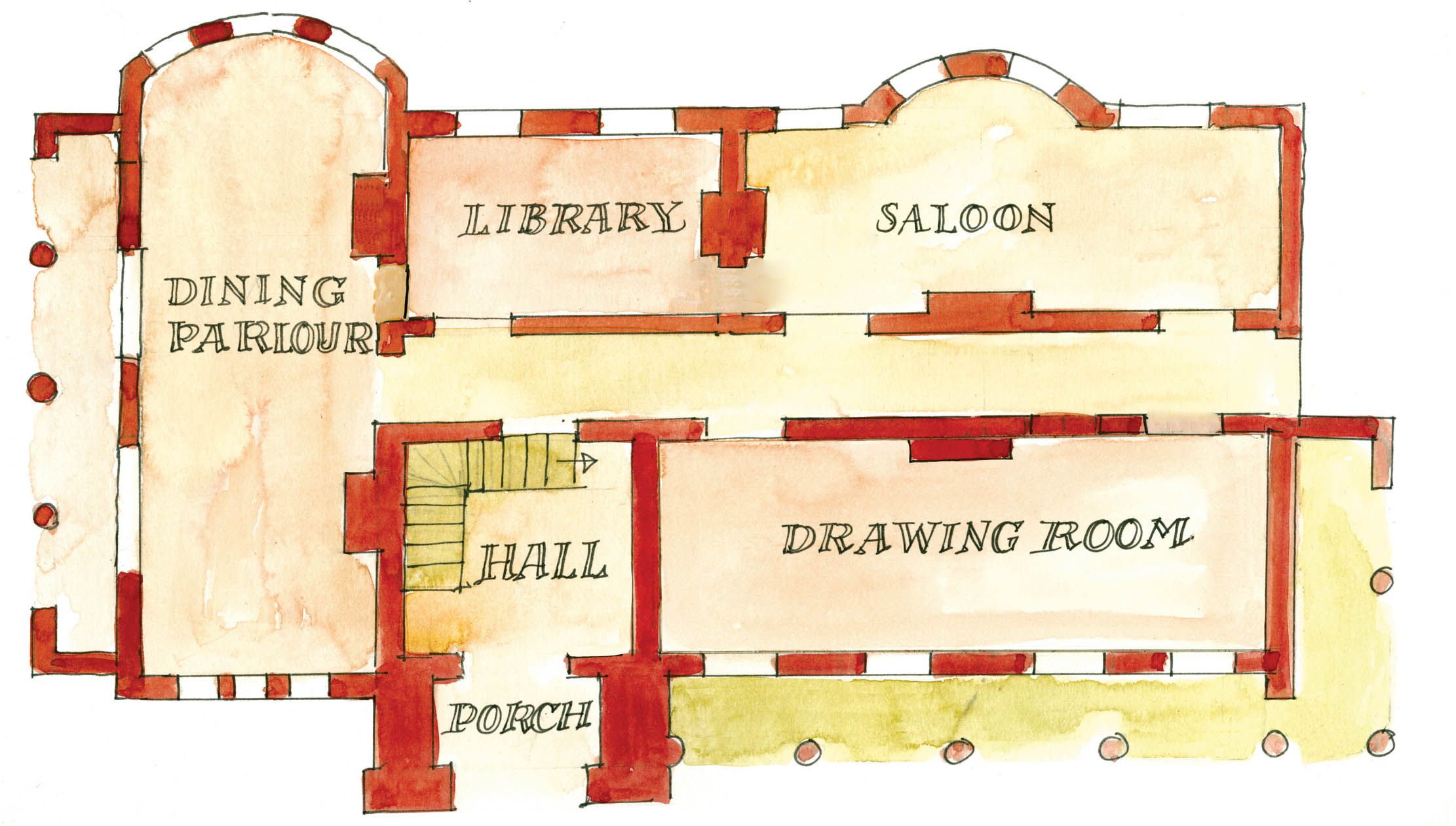

Ferrars strongly advises him to build a cottage instead and he tells the Dashwoods, in a passage that is perhaps the longest architectural description in Austen, about a house in Kent (Fig 2), also an easy step from London: ‘I was last month at my friend Elliott’s, near Dartford. Lady Elliott wished to give a dance. “But how can it be done?” said she; “my dear Ferrars, do tell me how it is to be managed. There is not a room in this cottage that will hold ten couple, and where can the supper be?” I immediately saw that there could be no difficulty in it, so I said, “My dear Lady Elliott, do not be uneasy. The dining parlour will admit eighteen couple with ease; card-tables may be placed in the drawing-room; the library may be open for tea and other refreshments; and let the supper be set out in the saloon (Fig 3).’

Ferrars then explains that they measured the dining-room and — happily — found it could indeed ‘hold exactly eighteen couple and everything was arranged to his plan’. He concludes: ‘So that, in fact, you see, if people do but know how to set about it, every comfort may be as well enjoyed in a cottage as in the most spacious dwelling.’ By way of judgement, ‘Elinor agreed to it all, for she did not think he deserved the compliment of rational opposition’. Quite so.

The life and times of Jane Austen

A potted history of one of our greatest literary influences.