The rather wise folly at Wolverton Hall: 'There isn’t a detail that I don’t think is extraordinarily deft and beautiful'

The new garden folly at Wolverton Hall in Worcestershire — owned by Nicholas and Georgia Coleridge — is inspired by Tudor and Georgian design, and provides the perfect retreat for study, entertainment and contemplation. Clive Aslet reports; all photographs by Paul Highnam for the Country Life Picture Library.

Follies are misnamed. Despite their small size, they can be very serious little buildings indeed, whether they are pioneering an architectural style, such as the 18th-century Greek Revival, before it is used elsewhere, or works of geometrical complexity, as was the case in the Elizabethan period. The new folly at Wolverton Hall is of the latter type, being constructed on an octagonal plan. Yet, for all the intensity of the architecture, its festive character seems to captivate everyone who sees it. If, says the owner, he had been given £5 by all the people who have expressed admiration, it would have paid for itself many times over.

That owner is Nicholas Coleridge, chairman of the V&A Museum and, until recently, CEO of the publishing group Condé Nast. (It was, says his wife, Georgia, emphatically his project — although, happily, she is among those who like the result.)

As an ambassador for the Landmark Trust, Mr Coleridge has a natural sympathy for small, architecturally potent structures and he and his family have stayed in many such. On retiring from Condé Nast, he wanted to create an agreeable study for himself, detached from the family home at Wolverton. He also had the natural desire to leave his mark on the place.

‘I always dreamt of having somewhere away from the house that would be architecturally interesting, where I could work. But I never thought we’d get planning permission,’ Mr Coleridge reflects. Nothing daunted: ‘I emboldened myself to email Quinlan Terry, whom at that stage I had never met.’

It was a better choice of architect than he might have known. Mr Terry is famous, of course, as the leading Classicist of his generation, his name being attached to numerous country houses of great splendour. Yet at the beginning of his career, when opportunities to build on a grand scale were fewer, he lavished care and thought on a series of small buildings, initially with the founder of his practice, Raymond Erith.

These included a series of several follies at West Green House, Hampshire, for the late Lord McAlpine, whom he met the day after Erith’s death in 1973; a flamboyantly purposeless column, erected two years later, at the midpoint of that dark decade, carried a Latin inscription that translates as: ‘This monument was built with a large sum of money, which would have otherwise fallen, sooner or later, into the hands of the tax-gatherers.’ The elliptical, spirally fluted urn was a mathematical challenge, without the possibility, in those days, of help from computer software.

In 1982, Mr Terry built a summer house for Michael Heseltine at Thenford, in all the glory of the Corinthian order, with a contrast of grey and tawny building stones. Some of these works were recorded in linocuts, a medium in which Mr Terry excelled: before joining Erith, he had been strongly attracted to the Arts-and-Crafts Movement (as can be seen from the decoration of his own house, Higham Hall, Suffolk). The scalpel and gouger have since passed to Mr Terry’s assistant Eric Cartwright, who has shown himself to be an equal master of the technique.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

At Wolverton, the first design decision was to find a site for the folly. There were three possibilities, one of which was in a field. ‘That would have been rejected by the planners,’ notes Mr Coleridge, ‘and I now think it would have been too far away.’ He settled instead on the walled garden. This is only a few dozen steps from the house, convenient both for the folly’s primary function as a study and its secondary role as a summer dining room. The sense of enclosure given by a tall beech hedge recalls the setting of Tudor banqueting houses, such as those which once graced Hampton Court.

What of the style? ‘I’d had an idea for something simpler,’ says Mr Coleridge, but Mr Terry ‘made it into something much more glorious than I could ever have imagined. He’s been right in every way.’

The inspiration was the 16th-century summer house at Long Melford in Suffolk, near Mr Terry’s base in East Anglia; the Coleridges and Mr Terry went to see it together. This is a two-storey octagonal building with corner buttresses, like the Wolverton folly. It is, furthermore, built of brick: the obvious material for Wolverton, where the main house is also of brick construction. ‘All the best things have been done before,’ says Mr Terry, typically. ‘You don’t want to be too original.’ However, the model, in this case, was not perfect.

The Long Melford summer house is reached by a flight of steps, rather too big for the building, and its proportions are somewhat dumpy. Height was important at Wolverton. Wherever he is, Mr Coleridge enjoys looking out over views, whether the rooftops of Siena or the pastoral landscape of Worcestershire. The folly had to be tall enough — 46ft — for a prospect and the height improves the proportions. Instead of gables, it has a parapet and flat roof, which has proved to be an exceptionally good place for an evening drink. The stairs emerge through a turret.

There is an implied story to the folly. Wolverton Hall was built in the early 18th century and Mr Terry likes to imagine that, when historians of the future come to consider the site, they will think that it belonged to a house that predated the present one.

The rosy orange brick from which the folly is built is of the old Tudor dimensions, 2in rather than 3in deep; it is laid with wide mortar joints that give lightness to the façade.

The first-floor window surrounds, in constrasting stone, rise to ogee heads, which then, above a string course, burst out as acanthus leaves. The buttresses at the corners of the octagon end in ball finials, giving, with the bell-shaped roof of the turret, the sort of fanciful skyline beloved of the Tudors — and of the Georgian folly makers who imitated their style. Think of the charmingly implausible gables of King John’s Hunting Lodge at Odiham, Hampshire.

In this fallen age, future generations will only have to consult Google to find the true date of the Wolverton folly. In any case, the description already given suggests that the sharpest architectural historians will not be deceived. ‘I call it a Georgian-Jacobean-Tudor melange,’ says Mr Coleridge. ‘Occasionally, I have a slight memory of Lupton’s Tower in School Yard at Eton [the gatehouse, built in 1520]. I am also reminded of Hampton Court’, although, unlike most Tudor buildings, it is — as Wolverton Hall itself is — flooded with light from the sash-windows.

Inside, the folly is, as every folly should be, intimate. Originally it was planned to be 2ft larger all round. This, however, would have made it rather more than a folly in terms of cost; unlike some country-house owners, who have shrunk the size of their rooms to save money and lived to regret it, Mr Coleridge is unabashed.

‘It would not have added to the happiness for it to have been bigger,’ he says. ‘The genius of it is to be like a perfect jewel inside and outside. There isn’t a detail that I don’t think is extraordinarily deft and beautiful.’

Another saving was made by using reconstituted stone. Even now, the difference from cut stone is not obvious and, in a few years’ time, even an expert would be hard put to judge. Only the Coleridge coat of arms — on which the otter symbolises Ottery St Mary, where the poet Coleridge had his Lime Tree Bower — was carved by hand.

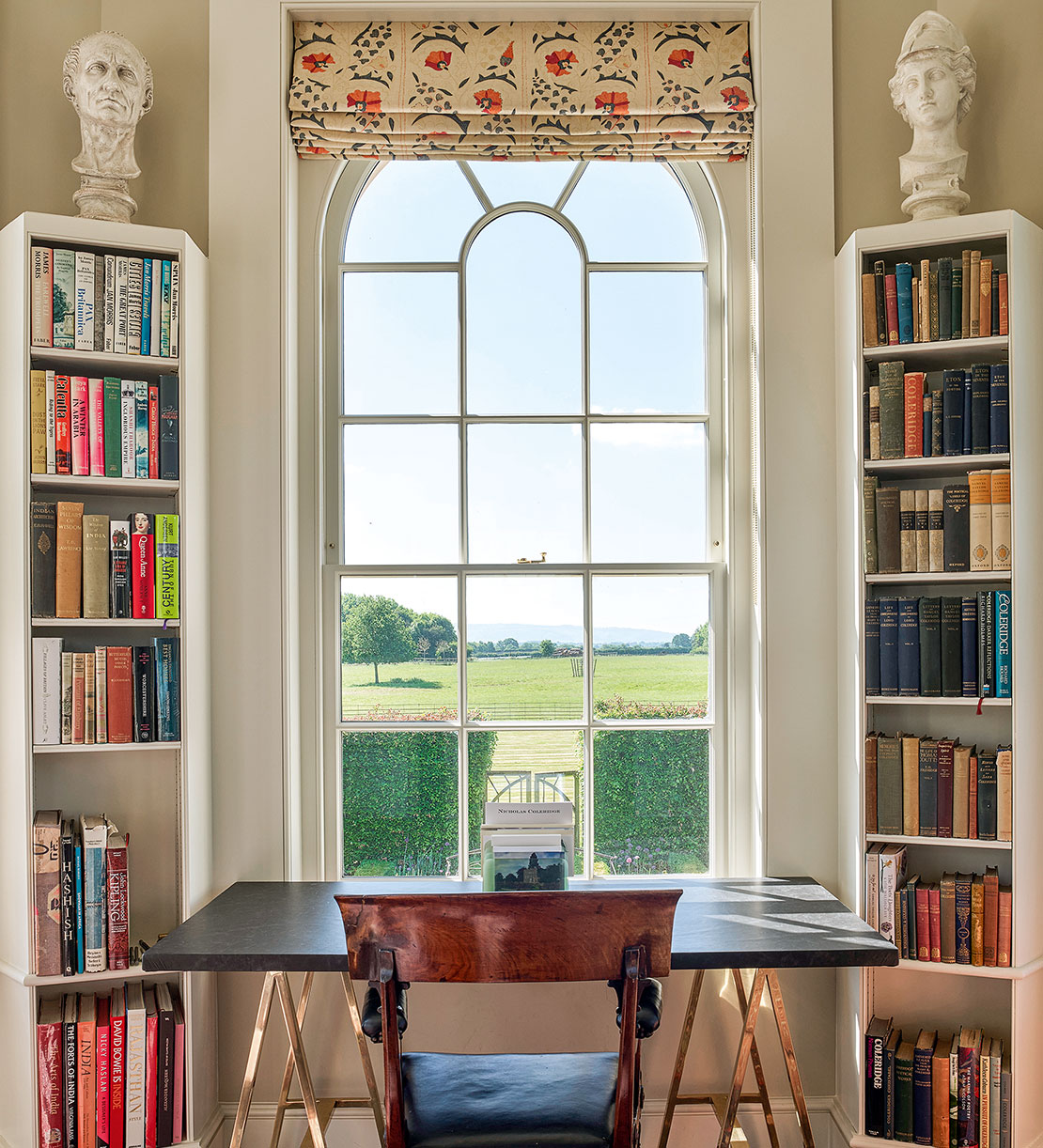

The front door gives into a plain room with an octagonal table; doors in the panelling are opened and, lo!, a tiny kitchen appears. This room is the perfect size for dinners of eight people. A concealed door reveals a small, yet perfectly formed lavatory, hung with a Persian paper copied from the gentleman’s lavatory at 5, Hertford Street, W1, the Mayfair club. The staircase, which a broad shouldered man might brush on both sides, has a wave-like skirting board and rises to the principal room — Mr Coleridge’s study, its bookshelves lined with volumes by Coleridges past and present. The family’s Vale of Evesham friend, Rosanna Bossom, oversaw the interior decoration.

An Indian theme is given by the pictures that Mr Coleridge collected on his many trips to the sub-Continent when establishing the Indian edition of Vogue. An antiqued panelled mirror was made to fit over the fireplace. Mr Coleridge held out for a gas rather than wood fire — he did not like the thought of carrying the logs. The plaster heads over the bookcases were bought from Christie’s South Kensington soon before it closed down. ‘They were being sold by an art school that said no one needed to do life drawing today — the exact opposite of The Prince of Wales’s Drawing School.’ A last flight of staircase leads up to the parapet. ‘I love sitting up there; it is an incredible suntrap.’

It is a source of considerable pride that nearly everyone who built the folly came from within a radius of a couple of dozen miles. The contractors were J. Rigg of Broadway. The roofers are based in Tewkesbury. The bricklayers hail from Moreton-in-Marsh and Evesham. The windows were produced in Pershore. The one exception concerns the acanthus leaves over the ogee-window surrounds, which were cast in Scotland.

Twenty-first-century follies are serious in another way. Although the foundations of the main house at Wolverton may be scant, the folly has been built to modern building regulations and is, its owner says, ‘probably the most robust structure ever made’. The brickwork is a joy in itself. No fewer than 24 different specials, drawn up to full size so that moulds could be made, were required to make the angles and curves. The result is a building of almost tactile delight.

The one sadness is that the opening party planned for June had to be postponed due to coronavirus. But the weeks of lockdown gave the Coleridges — nine in all, with adult children and other halves who had come for the duration — plenty of time to acquaint themselves with the new tower. All of us have been spending rather longer contemplating our domestic surroundings than we might ideally like, given the many weeks spent confined to quarters. Investing in a beautiful space in which to work, eat and enjoy the view does not, under these circumstances, seem a folly at all, but a remarkably wise decision.

My favourite painting: Nicholas Coleridge

Nicholas Coleridge chooses Maharana Jagat Singh attending an elephant fight by Syaji and Sukha as his favourite painting

England’s best view? Tintagel, Cornwall, where seas of turquoise crash on slate tinged with copper

Simon Jenkins chooses Tintagel, Cornwall as one of England’s best views.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

In praise of nightingales: 'I’ve listened to Gregorian chants in Gothic cathedrals — but the greatest musical performance I ever heard was outside my bedroom one night'

It’s 200 years since Keats penned ‘Ode to a Nightningale’, but this otherwise drab bird’s rich, sorrowful song is worth

Credit: Melanie Johnson

A foolproof recipe for raspberry soufflé pancakes that offers a delicious little taste of summer

Sometimes you'll have hours to spend in the kitchen making ludicrously-complicated recipes involving umpteen processes and hard-to-find ingredients. At other

Jason Goodwin: Is the answer to finding faith really as simple as "fake it 'til you make it"?

The ancient Ottomans knew the power of repetition to shape the minds of others — something that Jason Good has discovered

-

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire garden

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire gardenDesigners from Sanderson have immersed themselves in The King's garden at Highgrove to create a new collection of fabric and wallpaper which celebrates his long-standing dedication to Nature and biodiversity.

By Arabella Youens

-

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’s

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’sThere are only 200,000 Birkin bags in circulation which has helped push prices of second-hand ones up.

By Lotte Brundle