The Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast: 'The Ulster acropolis'

In the second of two articles marking the centenary of the establishment of the Northern Ireland Parliament, John Goodall looks at the Art Deco seat created to accommodate it. Photographs by Paul Highnam

In November 16, 1932, Edward, Prince of Wales, arrived in Belfast to open the newly completed Parliament Buildings at Stormont on behalf of George V. The Prince was a veteran of such events, having already played a ceremonial role in the establishment of parliaments across the British Empire from Valletta to Canberra. Where they were provided with new buildings — to make outward expression of the political change they represented — these early 20th-century institutions of nascent statehood shared much in common.

All the new parliaments and assembly buildings were monumental works of Classically informed architecture, an idiom particularly associated at the time with the dignity of government and authority. All formed the centrepiece of park-like, governmental districts that were a hallmark of British Imperial power. And all of them assumed a governing structure borrowed from the example of Westminster, the ‘Mother of Parliaments’, with an upper and a lower house.

As we saw last week, the Parliament Buildings of Northern Ireland were planted on an estate purchased for the purpose a century ago in 1921. Stormont originally lay outside the bounds of Belfast, but was formally incorporated within the city to serve its new governmental role. The 1850s castle at the heart of the estate was adopted as the home of the Prime Minister and plans were set in motion to erect new buildings that would accommodate the legislative and executive functions of state.

"At the centre is a portico and pediment, the latter ornamented with sculpture that has been variously interpreted as Northern Ireland presenting the flame of loyalty to Britain or Britain passing the flame of liberty to Northern Ireland"

Two architects were initially appointed to the task. The First Commissioner of Works, who was responsible for the project on behalf of the British government, requested a list of suitable professionals from the Royal Institute of British Architects and — to the considerable annoyance of other aspirants to the work — chose two names from it without competition. Both of them had experience of civic architectural commissions, which presumably recommended them for the task.

The first was Ralph Knott, well known at the time for the design of the vast London County Hall on the south bank of the Thames opposite Westminster, which opened in 1922. The other was the Liverpool-based architect Arnold Thornely. He had been involved in the ambitious commercial redevelopment of his home city, but had also worked on such buildings as the Wallasey Town Hall on the Wirral, begun in 1914. Knott was commissioned to work on the proposed government office buildings and Thornely on the parliament.

The slope of the site overlooking Co Down and Belfast naturally suggested a symmetrical composition, with the parliament elevated on a retaining wall between and above flanking office blocks. To lend visual emphasis to the former, it was to be surmounted by a central tower with a dome. The idea of a central dome on a tall base was a commonplace of Edwardian public buildings and modestly prefigured by Thornely at Wallasey. In this case, however, the dome was clearly — and pointedly — inspired by that over Belfast City Hall, which was completed in 1906.

Excavation of the foundations for the new buildings began in 1924, but the estimated costs spiralled from £1,350,000 to £1,750,000 and, in November 1925, at the behest of the Treasury, the commission was fundamentally revised. Knott’s offices were abandoned and Thornely was told to accommodate them in the parliament building (the compression of several structures into one explains the slightly confusing modern name ‘Parliament Buildings’).

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This change and the removal of the dome reduced the estimated costs to £1,250,000 and James, 3rd Duke of Abercorn, the first Governor of Northern Ireland, laid the foundation stone on May 19, 1928.

Despite the cost-cutting, Thornely’s building was an extravagant one. It is in a neo- Grecian style with a main façade of Portland stone 365ft across. This rises from a rusticated base — the wide masonry joints giving an impression of solidity — and incorporates four serried ranks of 27 windows. The largest and most richly detailed windows are on the first floor, identifying this as the main internal level. At the centre is a portico and pediment, the latter ornamented with sculpture that has been variously interpreted as Northern Ireland presenting the flame of loyalty to Britain or Britain passing the flame of liberty to Northern Ireland.

As the Parliament Buildings rose from the ground, the Stormont estate was transformed under the direction of W. J. Bean, a former curator of Kew Gardens, and the horticulturist H. A. Moore. As part of their work, a processional avenue nearly a mile long was constructed in direct alignment with the central portico across steep natural gradients. It cost the immense sum of £57,000 to build.

Two-thirds of the way along the avenue is a roundabout commanded by a 12ft-high statue of the Unionist barrister and politician Edward Carson, erected shortly after the official opening in 1933. Easily overlooked beside this huge figure are the remarkable bronze benches supported on human figures around the statue base.

Double plantings of elms were planned along the lower length of the avenue, but these were presciently substituted for red-twig lime for fear of Dutch elm disease. The trees are positioned in converging lines so as to exaggerate the length of the view. To either side of the main carriageway are pavements lined with lamp posts, each one bearing the crest of an Irish elk and the arms of Ulster. Thornely also designed the gates and lodges for the main entrances to the park.

"The Great Hall is suffused with the brilliant aesthetic of the Art Deco"

One peculiarity of the avenue is that it does not properly lead to the Parliament Buildings. Instead, it terminates at the foot of a massive flight of 60 steps that rises to the main front (Thornely attempted something similar on the river front of Wallasey Town Hall). From the bottom of the steps, the building looks like an acropolis isolated on its own hill. Modern access is from one side (rather than the steps), but both approaches ultimately lead to the original main entrance at the base of the façade’s central portico.

Passing through this, the visitor enters the aisled space of the Central or Great Hall, which is suffused with the brilliant aesthetic of the Art Deco. The walls are covered in polished travertine marble and the patterns of the inlaid floor and the deeply coffered ceiling echo each other. The former is again of travertine and the latter richly silvered. At the far end of the interior is a flight of stairs commanded by a large statue of James Craig, Lord Craigavon, the first prime minister of Northern Ireland, unveiled in 1945.

Down the length of the room are five gilded chandeliers, the largest of them gifted by Kaiser Wilhelm to Edward VII and subsequently from George V to the Parliament Buildings.

Immediately below this huge fitting, facing each other midway down the room, are two large travertine doorcases. These lead respectively to what were once the Commons and Senate Chambers, via circular lobbies with low domes, lit by internal light wells. The lobbies are of distinct design, but internally faced with marble and furnished with curved benches.

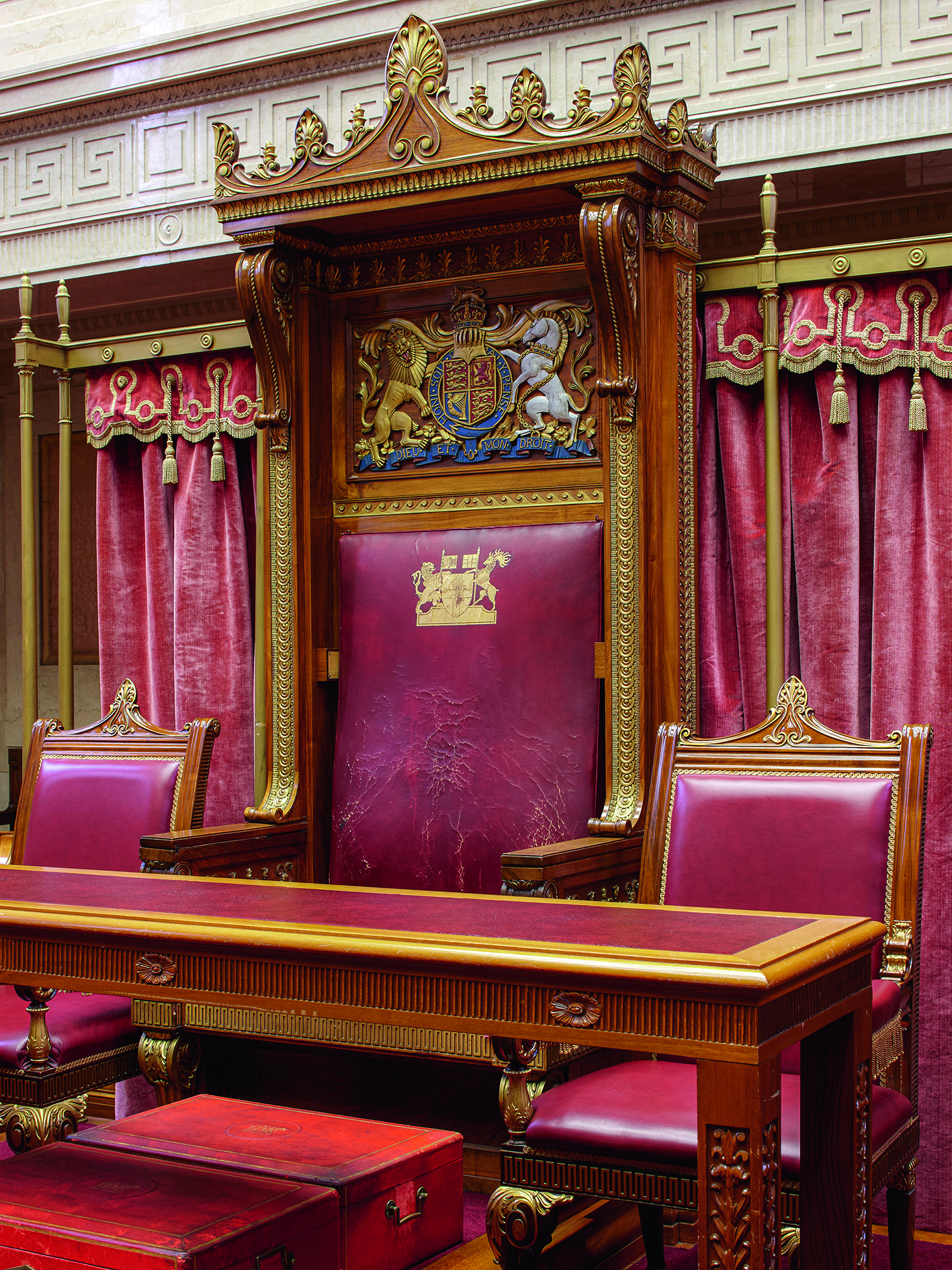

The parliament chambers are aligned across the full width of the building at right angles to the entrance hall. As at Westminster, the speaker’s chairs in each distantly face each other. The Senate Chamber, which is now used as a committee room by the Northern Ireland Assembly, is furnished in the style of the House of Lords in red (although the Irish linen damask wall covering has now faded to pink) and is strikingly ornamented with ebonised mahogany columns and a ceiling that incorporates panels of electric lights, in the most up-to-date Art Deco manner. There are galleries at either end. The chamber was designed to house a senate of 24 members elected by the Commons; the elected mayors of Belfast and Londonderry also had seats.

The Commons Chamber originally accommodated 52 members, elected by universal adult suffrage. They sat in confrontationally ranged benches to either side of a speaker’s chair, after the manner of Westminster. The chamber was panelled in burr walnut and, as did the Senate, possessed galleries to either end. Its appearance today respects Thornely’s design, but is, in fact, entirely modern.

Thornely compressed the parliamentary interiors, together with their associated services, library and conference room, into the lower two floors of the building. Connecting this warren of rooms is a grid of broad corridors that criss-crosses the plan. Offices for the administration of Northern Ireland were accommodated in the upper two floors of the Parliament Buildings.

When it opened in 1932, the Parliament Buildings divided critical opinion, although judgements on both sides were coloured by political sympathies. What Thornely sought to create was a modern and industrial building — in terms of scale, consistency of detail and services — but in a Classical idiom.

That treatment was common in the 1920s and 1930s, but is unusual to see in Britain outside city centres, such as London and Liverpool, where competing buildings soften the scale. It hasn’t helped the 20th-century reputation of Stormont that the blend of modernity and Classicism it expresses were ruled unacceptable by doctrinaire Modernists, who oddly maintained that the two were mutually exclusive.

Thornely went on to create other buildings deeply indebted to Stormont, notably the Town Hall of Barnsley, South Yorkshire, opened in November 1933 by the Prince of Wales. Curiously, the composition of building and avenue is reputed to have inspired the Bulange or Bugandan Parliament, in Kampala, Uganda, begun in 1953 by King Ssekabaka Muteesa II, who possibly visited during a period of exile.

Within a decade of being opened, the building was transformed by the Second World War. Much of the interior was commandeered by the RAF, which used the Senate as an operations room (the Senate itself relocated to the Members’ Dining Room). The exterior was covered with a mixture of bitumen and cow dung to camouflage the Portland stone.

"What he sought to create was a modern, industrial building, in a Classical idiom"

The Parliament Buildings and its institutions survived the Second World War, but, in March 1972, intensifying political difficulties in Northern Ireland resulted in the imposition of direct rule from Westminster. Parliament was then suspended and, during the dark days of the Troubles, Stormont became an inaccessible landmark.

Two short-lived attempts to restore government were initiated in 1973 and 1982, with assemblies that occupied the Commons Chamber; to accommodate the first of these, the benches within it were reconfigured in a more consensual U-shape. In 1995, a major fire gutted the interior of the room and otherwise did substantial damage to the building.

In the aftermath of the fire, the decision was taken to restore the interior of the Commons Chamber using Ulster expertise and craftsmanship. The panelling was re-created and two new galleries were added to the sides of the room. Other important changes also followed on from the fire in the building as a whole, including the creation of a Long Gallery from three upper rooms in the main front with superb views. It is a space usually used for public events and receptions and, during lockdown, was the scene of televised Covid briefings.

The restoration of the Parliament Buildings after 1995 was completed during a period of direct rule from Westminster. It took several more years, with protracted negotiations for peace culminating in the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, for devolved power to be restored and a Northern Ireland Executive — with its offices in the neighbouring Stormont Castle — to be elected in November 1999.

Since that time, the original Commons Chamber has been the seat of the Northern Ireland Assembly. Its symbol of six flax flowers, referring to the six counties of Ulster and the historic importance of the linen trade, is emblazoned on the blue carpet of the room. Over the past 20 years, this Assembly has survived several suspensions and — as this article goes to press — is again in crisis.

What is very heartening about Stormont, nevertheless, is the way in which the Parliament Buildings and the surrounding parkland have been opened up to the public over the past two decades and that the latter, in particular, has become a much-loved Belfast amenity. In this regard at least, Westminster has something to learn from Stormont.

For opening hours of the Northern Ireland Assembly, visit www.niassembly.gov.uk

Stormont Castle: How a 'plain house' in Belfast became the seat of power

A century ago, the Stormont estate was chosen as the seat of the government of Northern Ireland. In the first

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa Harrison

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa HarrisonThe novelist, children's author and nature writer Melissa Harrison joins the podcast to talk about her love of the natural world and her new app, Encounter.

By James Fisher

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes